Eupatorium rotundifolium

| Eupatorium rotundifolium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo was taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Eupatorium |

| Species: | E. rotundifolium |

| Binomial name | |

| Eupatorium rotundifolium L. | |

| |

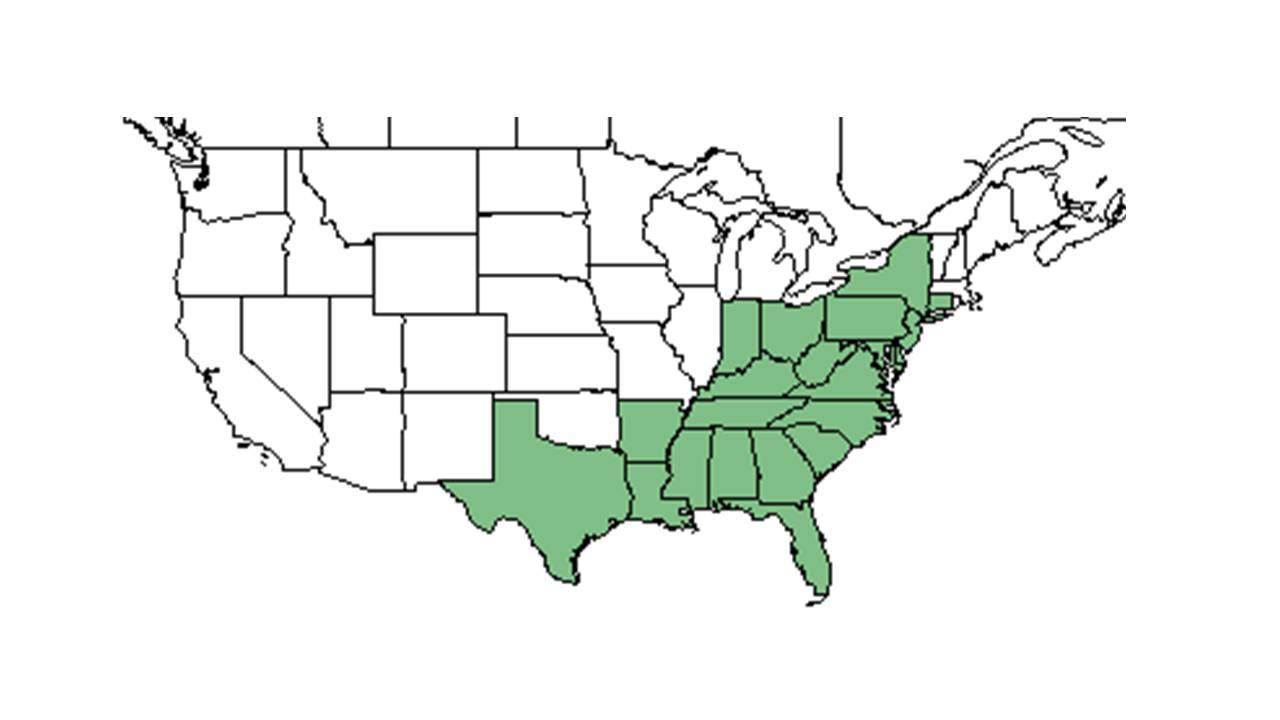

| Natural range of Eupatorium rotundifolium from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: roundleaf thoroughwort; common roundleaf Eupatorium

Contents

[hide]Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

A description of Eupatorium rotundifolium is provided in The Flora of North America.

Distribution

E. rotundifolium is distributed from Massachusetts, New York, Indiana, and Oklahoma south to southern Florida and Texas.[1]

Ecology

It has well-documented anticancer activities against various human cancer cell lines.[2]

Habitat

E. rotundifolium is generally found in seepage bogs, savannas, and woodlands.[1] It has been observed in river bottoms, creek bluffs, slash pine-palmetto flatwoods, near streams, in open-dry habitats, mixed woodlands, savannas, marshy areas, bottomland woodlands, edges of thickets, edges of titi swamps, open boggy areas, Longleaf pine-wiregrass savannas, and well-drained uplands. It is also found in human disturbed areas such as pinelands that have been clear cut and plowed, roadside edges and ditches, in a drainage ditch, in roadside thickets, powerline corridors, in plowed pastures, and in fire breaks bordering pine flatwoods. [3] It can be found in areas regularly burned every 1 to 2 years in the winter. It can be found in longleaf pine savanna communities.[4]

Associated species include Pinus taeda, P. palutris, P. elliottii, Serenoa repens, Taxodium distichum, Liquidambar styraciflua, Sabatia, Lilium, Eupatorium pilosum, E. semiserratum, E. recurvans, E. leucolepis, E. compositifolium, Ceanothus microphyllus, Ctenium, Rhus, Rubus, Aster spinulosus, Myrica cerifera, Magnolia virginiana, Aristida stricta, Cyrilla racemiflora.[3]

Phenology

E. rotundifolium generally flowers from August until October.[1] It has been observed flowering from May to November with peak inflorescence in July and fruiting from July to November.[3][5]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind. [6]

Seed bank and germination

It was found in the seed bank of a New England coastal plain pond in Massachusetts.[7]

Fire ecology

It is fire-tolerant.[4] A study on fire seasonality found E. rotundifolium to benefit from summer burn regiments rather than winter or spring burn regiments.[8] Another study found this species to increase in abundance 6 months after a fire disturbance, but to decrease in frequency after this point.[9] Populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burning.[10]

Pollination

E. rotundifolium is considered to be of special value to native bees by pollination ecologists since it attracts large numbers of native bees for pollination.[11]

Herbivory and toxicology

It also functions as forage for some wildlife species.[12][13][14][15]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

This species is listed as possibly extirpated by the Maine Department of Conservation, Natural Areas Program.[16] It is also critically imperiled in Oklahoma, and vulnerable in Pennsylvania and Indiana.[17]

Cultural use

Medicinally, this species has been used in the past to treat intermittent fevers.[18]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- Jump up ↑ Kintzios, S. E. (2007). "Terrestrial plant-derived anticancer agents and plant species used in anticancer research." Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 25: 79-113.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: R.K. Godfrey, Jean Wooten, Victoria Sullivan, Delzie Demaree, Ed Keppner, Lisa Keppner, Clarke Hudson, Carol Havlik, Loran C. Anderson, Nancy E. Jordan, J. P. Gillespie, J. Wooten, J. Lazor, R.L. Lazor, Gwynn W. Ramsey, Richard S. Mitchell, A. F. Clewell, K. Craddock Burks, R. Kral, P. L. Redfearn, Jr., Olga Lakela, Kurt Blum, Doug Gae, R. A. Norris, and Cecil R Slaughter. States and Counties: Arkansas: Lafayette and Sevier. Florida: Alachua, Bay, Calhoun, Citrus, Columbia, Duval, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Gilchrist, Gulf, Hernando, Highlands, Hillsborough, Holmes, Jackson, Jefferson, Lake, Lee, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Nassau, Okaloosa, Okeechobee, Orange, Osceola, Pasco, Polk, Putnam, Santa Rosa, Sarasota, St. John’s, Suwannee, Taylor, Union, Wakulla, and Washington. Georgia: Grady and Thomas. South Carolina: Jasper.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Brewer, J. S. and S. P. Cralle (2003). "Phosphorus addition reduces invasion of a longleaf pine savanna (southeastern USA) by a non-indigenous grass (Imperata cylindrica)." Plant Ecology 167: 237-245.

- Jump up ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 9 DEC 2016

- Jump up ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- Jump up ↑ Neill, C., et al. (2009). "Distribution, species composition and management implications of seed banks in southern New England coastal plain ponds." Biological Conservation 142: 1350-1361.

- Jump up ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- Jump up ↑ Schmalzer, P. A. and C. R. Hinkle (1992). "Recovery of Oak-Saw Palmetto Scrub after Fire." Castanea 57(3): 158-173.

- Jump up ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- Jump up ↑ [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 10, 2019

- Jump up ↑ Denhof, Carol. 2018. Plant Spotlight Eupatorium rotundifolium (L.) Roundleaf Thoroughwort. The Longleaf Leader. Vol. XI, Issue 2. Pg. 6

- Jump up ↑ Miller, J.H. and K.V. Miller. Forest Plants of the Southeast and their Wildlife Uses. The University of Georgia Press, Athens, GA. 454pp.

- Jump up ↑ Sorrie, B.A. 2011. A Field Guide to Wildflowers of the Sandhills Region. The University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill, NC. 378pp.

- Jump up ↑ USDA, NRCS. 2019. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 16 May 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- Jump up ↑ USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 10 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- Jump up ↑ [[2]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: May 10, 2019

- Jump up ↑ Porcher, F. P. (1869). Resources of the southern fields and forests, medical, economical, and agricultural. Richmond, VA, Order of the Surgeon-General.