Eragrostis spectabilis

Common Names: purple lovegrass [1], showy love grass [2], tumblegrass [3]

| Eragrostis spectabilis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Genus: | Eragrostis |

| Species: | E. spectabilis |

| Binomial name | |

| Eragrostis spectabilis Pursh | |

| |

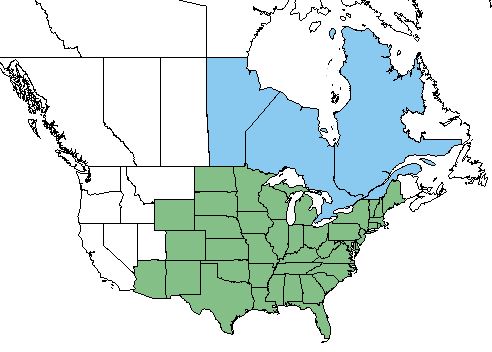

| Natural range of Eragrostis spectabilis from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: none[4]

Varieties: Eragrostis spectabilis var. sparsihirsuta Farwell; E. spectabilis var. spectabilis[4]

Description

E. spectabilis is a perennial graminoid that is a member of the Poaceae family native to North America.[1] Generally reaches heights between 1 and 3 feet with leaf blades 8 to 18 inches in length. Leaves densely hairy, taper to a fine point, and are stiffly ascending when they are young. Sheath of the leaf is longer than the internodes, and covered with long grey hair. Hairy ligule; seedhead is an open panicle which is bright purple when mature. Tuft of hair located in axial of seed stalks, and spikelets range from 6 to 12 flowers.[5]

Distribution

E. spectabilis is found throughout the majority of the 48 continental United States excepting the far west. It has also been introduced to eastern Canada. [1] This species is considered to be an exotic in the states of Wyoming and Colorado.[6]

Ecology

Habitat

Ideal habitats for E. spectabilis are sandy fields, roadsides, and woodlands.[7] Habitats that this species has also been observed in include wet pine flatwoods, dry sand open field, sandy vacant lots, pine woodlands, dry woods, upland pine oak woods, coarse sand regions with scrub barrens, and other disturbed areas such as roadsides and parking lots.[8] Soils that this species is mostly adapted to include medium- and coarse-textured soils.[5] It grows most abundantly on moist and sandy soil that is in full sun.[9] In Florida, it is an indicator species of the clayhill longleaf woodlands habitat.[10] One study found that E. spectabilis grew more abundantly with needlefall rather than without it.[11]

E. spectablilis has shown positive regrowth in reestablished native pine woodlands that were disturbed by agricultural practices in South Carolina coastal plain communities, making it an indicator species for post-agricultural woodland.[12] E spectabilis was found to be an increaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[13]

Associated species include Cyperus sp., Pinus palustris, Pinus serotina, Aristida sp., Quercus laevis, Andropogon gerardii, Cyrilla racemiflora, Eragrostis elliottii, Taxodium ascendens, and others.[8]

Eragrotstis spectabilis is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[14]

Phenology

Generally, this species flowers from August until October.[7]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.[15] The weak seedheads at the top of the grass stalks will break off and get dispersed by the wind as well.[5]

Seed bank and germination

It has been observed to germinate from the seed bank of pine savanna habitats.[16] One study found seeds to germinate from the seed bank of successional old fields sites that were 15 and 85 years old.[17]

Fire ecology

Populations of Eragrostis spectabilis have been known to persist through repeated annual burns,[18][19] and controlled annual burning is beneficial to the grass; it will increase if the region is annually burned.[5] E. spectabilis has been observed to grow in areas that are burned by both anthropogenic (prescribed fire) and natural (lightning) occurrences. It has also been observed in annually burned areas as well as habitats burned on a 2 year regiment.[8] One study found this species to benefit more from springtime burns rather than summertime burns.[20]

Herbivory and toxicology

E. spectabilis consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet for various terrestrial birds.[21] It is used by livestock for grazing in the spring. Deer will dig up the basal part of the stem and eat it during the winter. [5] This species is also highly deer resistant.[9]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

This species is considered to have weedy or invasive characteristics according to Nebraska and the Great Plains region.[1] E. spectabilis is not a key management species since it is usually not abundant enough, but can add a variety to the diet of livestock. Maximum production is reached if no more than 50% of the current year's growth is grazed by livestock, and to improve plant vigor, grazing in the summertime should be deferred for at least 90 days.[5]

E. spectabilis can be used for planting at longleaf pine restoration sites to help restore the herbaceous ground cover.[22]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 USDA Plant Database

- ↑ Battaglia, L. L., et al. (2002). "Sixteen years of old-field succession and reestablishment of a bottomland hardwood forest in the lower Mississippi alluvial valley." Wetlands 22(1): 1-17.

- ↑ Robertson, K. R., et al. (1997). Delineation of natural communities, a checklist of vascular plants, and new locations for rare plants at the Savanna Army Depot, Carroll and Jo Daviess Counties, Illinois. Champaign-Urbana.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Magee, P. (2012). Plant Fact Sheet: Purple Lovegrass Eragrostis spectabilis. N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture. Baton Rouge, LA.

- ↑ [[1]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: May 8, 2019

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Loran Anderson, Cecil Slaughter, R.K. Godfrey, John Nelson, Gary Knight, H. Kurz, Robert Lazor, A.f. Clewell, George Cooley, Erdman West, Tom Daggy, R.E. Perdue Jr., A.H. Curtiss, Sidney McDaniel, R.Norris, R.Komarek, Karen MacClendon, Floyd Griffith) States and counties:Florida (Wakulla, Flagler, Franklin, Leon, Liberty, Gilchrist, Taylor, Bay, Palm Beach, Levy, Duval, Lafayette, Calhoun, Indian River, Washington, Holmes) Georgia (Thomas, Grady, Clinch, Atkinson)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 [[2]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 8, 2019

- ↑ Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ Harrington, T., et al. (2003). "Above and Below ground Competition from Longleaf Pine Plantations Limits Performance of Reintroduced Herbaceous Species." Forest Science 49(5): 681-695.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Leicht-Young, S. A., et al. (2009). "A comparison of seed banks across a sand dune successional gradient at Lake Michigan dunes (Indiana, USA)." Plant Ecology 202: 299-308.

- ↑ Oosting, H. J. and M. E. Humphreys (1940). "Buried viable seeds in a successional series of old field and forest soils." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 67(4): 253-273.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Towne, E. G. and K. E. Kemp (2008). "Long-term response patterns of tallgrass prairie to frequent summer burning." Rangeland Ecology & Management 61: 509-520.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Dagley, C. M., et al. (2002). "Understory restoration in longleaf pine plantations: Overstory effects of competition and needlefall." Proceedings of the eleventh biennial southern silvicultural research conference.