Endodeca serpentaria

| Endodeca serpentaria | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Aristolochiales |

| Family: | Aristolochiaceae |

| Genus: | Endodeca |

| Species: | E. serpentaria |

| Binomial name | |

| Endodeca serpentaria L. | |

| |

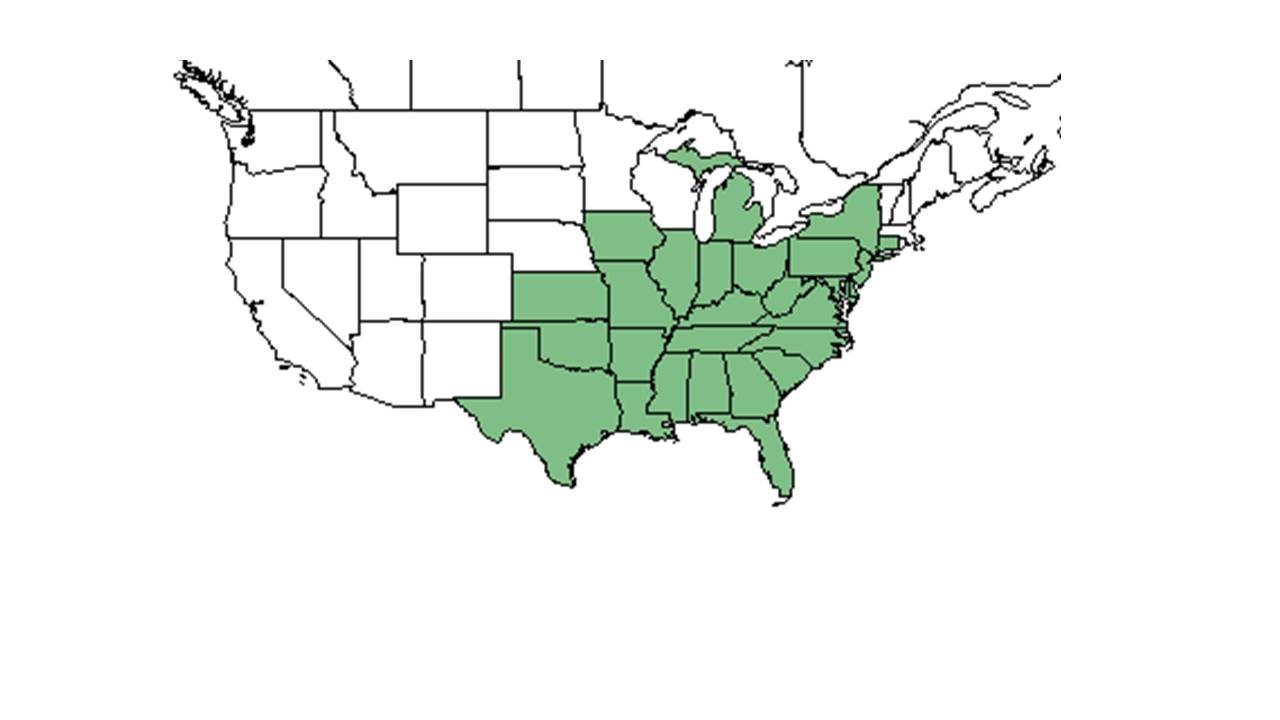

| Natural range of Endodeca serpentaria from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Turpentine-root, Virginia snakeroot, Serpent birthwort

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Aristolochia serpentaria (L.); Isotrema serpentarium (Linnaeus) X.X. Zhu, S. Liao, & J.S. Ma[1]

Varieties: A. hastata Nuttall; A. serpentaria var. hastata (Nuttall) Duchartre; A. convolvulacea Small; Endodeca hastata (Nuttall) Rafinesque; Endodeca serpentaria (Linnaeus) Rafinesque; Endodeca serpentaria var. hastata (Rafinesque) C.F. Reed[1]

Description

A description of Endodeca serpentaria is provided in The Flora of North America. The variation of this species needs to be further studied.[1] The rootstock, which has been used in the past for various medical ailments, has a camphor-like and aromatic odor, and tastes bitter, warm, and camphoraceous.[2]

Distribution

It is found as north as Connecticut, west to Illinois, and south to central peninsular Florida, then west to Texas.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

E. serpentaria is commonly found in mesic to dry forests, where it is more likely restricted to mesic areas over acidic substrates, and ranging into drier soils over calcareous or mafic substrates as well. [1] This species grows in mesic woodlands, rich mixed woodlands along creeks, wooded floodplains, and hardwood slopes. It is found in floodplains or slopes in soils varying from dry to wet sandy loam. This species has also been spotted in disturbed areas such as fire breaks. It thrives in shaded environments as well.[3] Full range of soils include sandy loam, medium loam, clay loam, and clay.[4] In the core range, E. serpentaria grows in association with limestone, but in its southeastern range it is more often found on other non-basic substrates. It is also often found on rocky slopes and near summits located in oak-hickory or other hardwood forests.[5] It is also listed by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service as a facultative upland and upland species, where it most commonly occurs in nonwetland habitats, but can occasionally be found in more mesic than hydric wetland areas.[6] This species is also considered an indicator species of the north Florida longleaf woodlands, and is characteristic of the north Florida subxeric snadhills as well.[7] It is more associated with native groundcover in the areas it is found, and not with old fields that were once agricultural areas.[8] E. serpentaria responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in Southwest Georgia.[9] E. serpentaria was found to be a decreaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[10]

In Alabama, associated species include Pinus echinata and Cornus florida.[5] Other associated species include Adiantum, Thelypteris, Quercus virginiana, Quercus laurifolia, Quercus sp., Betula nigra, and others.[3]

Phenology

Generally, this species flowers from May until June and fruits from June until July.[1] It has been observed to flower in April and May with peak inflorescence in May.[11]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.[12]

Fire ecology

E. serpentaria is characteristically found in habitats, like pine savannas, that are fire-dependent,[7] and populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[13]

Herbivory and toxicology

This species attracts butterflies, and is a larval host for Battus philenor (family Papilionidae).[4]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

E. serpentaria is listed as threatened by the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection, by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, Endangered Species Protection Board, by the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Parks, Recreation, and Preserves Division, and by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, Natural Features Inventory. This species is also listed as endangered by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Land and Forests.[6]

Cultural use

For humans, the root is said to have medicinal properties, including as a febrifuge, emmenagogue (promoting menstruation), stimulant, and acrid.[14] It was useful for low grade fevers, typhus after remittent, chlorosis, and atonic affects of the intestinal canal. Its effects are also noted to increase with camphor included.[15]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Sievers, A. F. (1930). American medicinal plants of commercial importance. Washington, USDA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: L. C. Anderson, R. R. Clinebell II, R. K. Godfrey, and M. Jenkins. States and Counties: Florida: Calhoun, Gadsden, Jackson, Lafayette, and Leon. Georgia: Thomas.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 6, 2019

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 [[2]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: May 6, 2019

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 6 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson (2007). A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, south Georgia, USA. Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems, Tallahassee, Tall Timbers Research Station.

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 6 MAY 2019

- ↑ Kirkman, L. K., et al. (2004). "Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna." Journal of Ecology 92(3): 409-421.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Nickell, J. M. (1911). J.M.Nickell's botanical ready reference : especially designed for druggists and physicians : containing all of the botanical drugs known up to the present time, giving their medical properties, and all of their botanical, common, pharmacopoeal and German common (in German) names. Chicago, IL, Murray & Nickell MFG. Co.

- ↑ Porcher, F. P. (1869). Resources of the southern fields and forests, medical, economical, and agricultural. Richmond, VA, Order of the Surgeon-General.