Eclipta prostrata

| Eclipta prostrata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Dennis Girard, Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Eclipta |

| Species: | E. prostrata |

| Binomial name | |

| Eclipta prostrata (L.) L. | |

| |

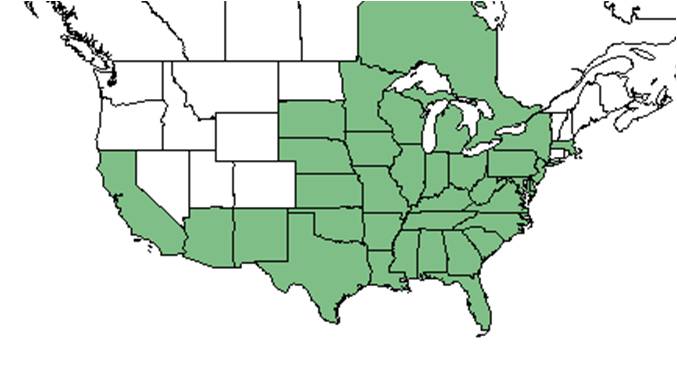

| Natural range of Eclipta prostrata from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: False daisy

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Eclipta alba (Linnaeus) Hasskarl; Verbesina alba Linnaeus.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Eclipta comes from the greek word "ekleipta" (deficient) which refers to the absence of the pappus on the achene.[2]

Description

A description of Eclipta prostrata is provided in The Flora of North America.

E. prostrata is an annual and can be a short-lived perennial in warmer climates. The reddish-purple stems are covered with short, stiff hairs and can grow prostrate or decumbent and branch occasionally. The leaves are subsessile, elliptic-lanceolate and arranged opposite, with a few blunt teeth along the margin. 1-3 composite flower heads on short pedicels emerge from the axils of the leaves. The ray florets are white, narrow, and short while the disk florets are cream with four small spreading lobes with pale yellow or light brown anthers emerging from them. The bracts form the base of the flowerhead and are green and triangular.[3]

Distribution

It is native to the Southeastern United States, but can also be found in Asia and South America.[4]

Ecology

Habitat

Eclipta prostata can be found in shallow water in shaded Acer-Nyssa-Taxodium swamps; cypress depression swamps; marsh edges; lake shores; river banks; brackish marshes; seepage areas in calcareous talus; moist sandy-peaty clearings of Baccharis flats; sandy loam of coastal hammocks; pine flatwoods; and river floodplains.[5] It is a noxious weed in many agricultural crops such as peanuts, soybean, cotton, rice, sugarcane and corn.[6] E. prostrata favors moist conditions and has been observed in gardens, holding ponds, and drainage ditches.[5] Substrate types include sandy peat, loamy sand and sandy loam soils.[5] Associated species include Typha, Erechtites, Ludwigia, Juncus, Mitreola, Fuirena, and Rhynchospora.[5]

Phenology

It has a composite flower head that consists of 8 to 16 green triangular bracts; narrow, white ray florets; and cream short disk florets with yellow or light brown anthers protruding.[3] Flowers June through November.[7]

Achenes are oblong, truncate at the top and tapering to a well rounded tip at the bottom and develop in a flowerhead after the petals fall off.[3]

Seed bank and germination

E. prostrata is a noxious weed in agronomic crops and container grown plants.[8] Seeds favor saturated conditions foer germination and are strongly photoblastic, no seeds will germinate without light.[6] Germination can occur over a range of temperatures from 10 to 35 C; however, germination has observed to have the highest rate (83%) at a constant temperature of 35 C. In peanut fields, it has been observe to germinate in the summer; and early rainfall, irrigation or wetter seasons favor germination in peanut fields.[9]

Pollination

Eclipta prostrata has been observed at the Archbold Biological Station to be visited by plasterer bees such as Hylaeus confluens (family Colletidae), sweat bees from the family Halictidae such as Halictus poeyi, Lasioglossum placidensis, L. puteulanum and L. tamiamensis, thread waisted wasps from the Sphecidae family such as Cerceris tolteca and Ectemnius rufipes ais, and wasps from the Vespidae family such as Parancistrocerus perennis anacardivora, P. salcularis rufulus and Stenodynerus fundatiformis.[10]

Herbivory and toxicology

Leaves contain nicotine, which acts as an insecticide.[3]

Diseases and parasites

It is a hosts for diseases to agricultural crops. It is a host for Sclerotinia blight which is caused by the fungus Sclerotinia minor which infests 25% of Oklahoma's peanut crops.[9] It is also a host of Amsacta moorei which feeds on young sorghum and castor beans.[6]

Reniform nematodes occasionally attack roots.[3]

Conservation and management

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Early control is necessary to prevent competition (Kranz et al. 1977). It is difficult to control with soil applied herbicides including metolachlor, imazethapyr, and vernolate. [11] Diclosulam and flumioxazin are able to control effectively when applied at 27 g ai/ha or 105 g/ha respectively.[12]

E. prostrata is a noxious weed in agricultural crops and container grown plants. Container grown landscape plants are vulnerable because they are typically grown in organic substrate and are irrigated frequently, conditions that E. prostrata favors for germination.[8] Roots can become established at the drainage holes of potted plants, keeping it protected from POST applied herbicides such as halosulfuron. The crown and lateral branches of E. prostrata are regenerative and make it more tolerant of halosulfuron applications.

Peanut are slow growing, making E. prostrata a competitor due to its ability to develop a canopy faster than the peanut.[11] It has also been observed to be a contaminant in rice seeds in the Philippines and reduce crop yields.[13]

Cultural use

It is claimed to be a powerful liver tonic.[14]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Fernald ML, 1950. Gray's Manual of Botany. 8th Ed. New York, USA: American.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 [Encyclopedia of Life] Accessed: December 9, 2015

- ↑ Holm LG, Plucknett DL, Pancho JV, Herberger JP, 1977. The World's Worst Weeds. Distribution and Biology. Honolulu, Hawaii, USA: University Press of Hawaii.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: October 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Linnea Angermuller, Sydney T. Bacchus, Kurt E. Blum, D. Burch, Andre F. Clewell, A.H. Curtiss, J.A. Duke, J. Dwyer, R.K. Godfrey, Ann F. Johnson, G.R. Knight, R. Kral, Robert L. Lazor, S.W. Leonard, H. Loftin, J.R. Martinez, Herbert Monoson, C. Nelson, R.A. Norris, Paul L. Redfearn Jr., Grady W. Reinert, Manuel Rimachi Y., Deborah R. Shelley, Sidney Thompson, Edwin L. Tyson, D.B. Ward. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Brevard, Calhoun, Citrus, Dixie, Flagler, Franklin, Hernando, Jackson, Jefferson, Lake, Lee, Leon, Liberty, Madison, Martin, Sarasota, Seminole, Wakulla, Washington. Georgia: Grady. Country: Columbia, Honduras, Panama, Peru. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Chauhan, Bhagirath S., and David E. Johnson. “Influence of Environmental Factors on Seed Germination and Seedling Emergence of Eclipta (eclipta Prostrata) in a Tropical Environment”.Weed Science 56.3 (2008): 383–388.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 19 MAY 2021

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Glenn R. Wehtje et al.. “Potential for Halosulfuron to Control Eclipta (eclipta Prostrata) in Container-grown Landscape Plants and Its Sorption to Container Rooting Substrate”. Weed Technology 20.2 (2006): 361–367.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 John V. Altom, and Don S. Murray. “Factors Affecting Eclipta (eclipta Prostrata) Seed Germination”. Weed Technology 10.4 (1996): 727–731.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 W. James Grichar et al.. “Weed Control with CGA-152005 and Peanut (arachis Hypogaea) Response”. Weed Technology 14.1 (2000): 218–222.

- ↑ Jordan, David L. et al.. “Peanut and Eclipta (eclipta Prostrata) Response to Flumioxazin”. Weed Technology 23.2 (2009): 231–235

- ↑ Rao AN, Moody K, 1990. Weed seed contamination in rice seed. Seed Science and Technology, 18(1):139-146

- ↑ [Natural Home Remedies] Accessed: December 7, 2015