Digitaria filiformis

| Digitaria filiformis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida – Monocotyledons |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae ⁄ Gramineae |

| Genus: | Digitaria |

| Species: | D. filiformis |

| Binomial name | |

| Digitaria filiformis (L.) Koeler | |

| |

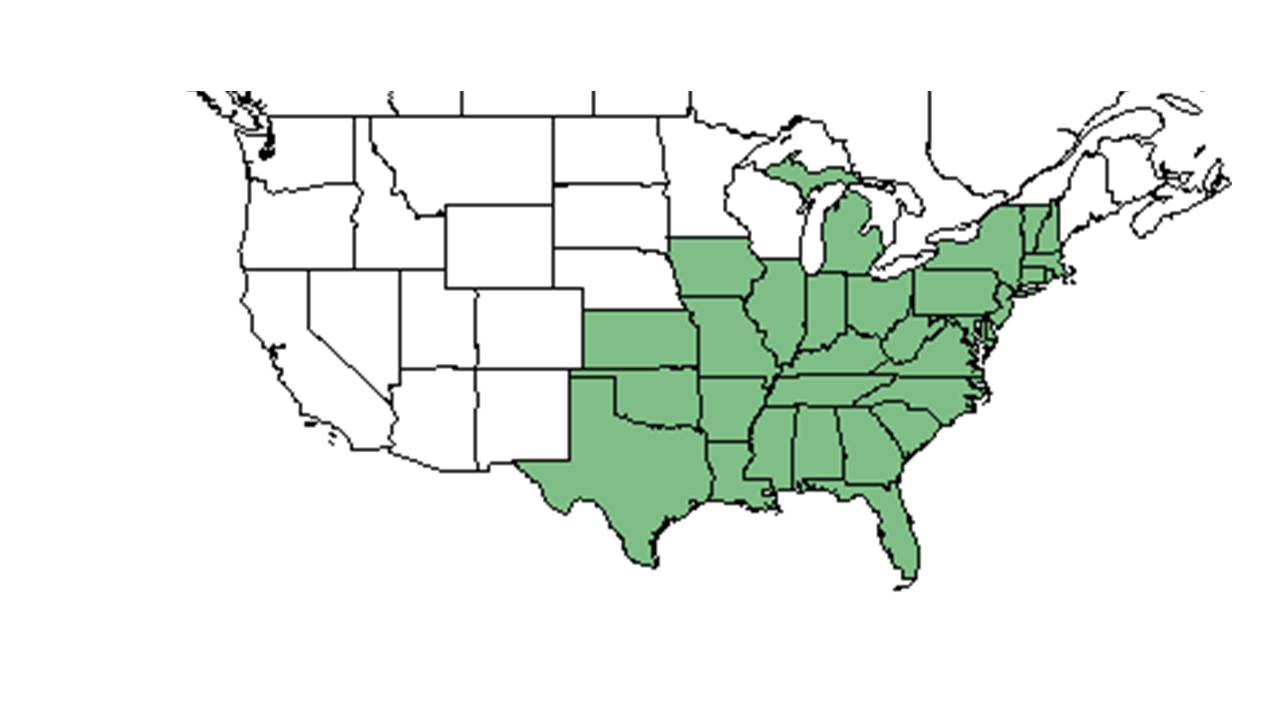

| Natural range of Digitaria filiformis from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Slender crabgrass

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Syntherisma filiformis (L.) Nash[1]

Varieties: Digitaria filiformis (Linnaeus) Köler var. filiformis[1]

There are three varieties. D. filiformis var. laeviglumis, D. filiformis var. filiformis; and D. filiformis var. dolichophylla. The variety laeviglumis is rare and endemic to New Hampshire in peaty depressions on granite ledges.[2]

Description

Generally, for the Digitaria genus, they are "annuals; internodes glabrous. Leaves cauline; blade margins cartilaginous, scaberulous; sheath margins usually scarious; ligules membranous. Racemes racemose, ascending; rachis usually winged, scaberulous. Spikelets plano-convex, ellipsoid, acute. First glume usually absent, 2nd glume villous on nerves and margins, acute, sterile lemma 5-7 nerved, acute; fertile lemma and palea nerveless, cartilaginous, glabrous, acute; fertile lemma margins flat, hyaline. Grain whitish to brownish, ellipsoid. These plants are out worst field and gardens weeds." [3] Specifically, for D. filiformis species, they are "cespitose annual; culms 3-12 dm tall, nodes glabrous. Blades to 15 cm long, 2-4 mm wide, papillose-hirsute and scaberulous above, glabrous or occasionally pilose to hirsute beneath; sheaths papillose-hirsute; ligules erose to lacerate, 0.5-1 mm long. Racemes 2-7, ascending, 3-12 cm long; rachis trigonous, wingless, scaberulous. Spikelets 1.8-2.5 mm long; pedicels scaberulous, -.5-3 mm long. Second glume 5- nerved, 1.2-1.5 mm long, sterile lemma margins ciliate, 1.8-2 mm long; fertile lemma and palea purple, papillose lined, 1.8-2 mm long. Grain 1-1.2 mm long, whitish to brownish, ellipsoid." [3]

Distribution

D. filiformis can be found in the eastern United States, from New Hampshire south to Florida, and west to Texas, Oklahoma, Iowa, and Michigan.[4] D. filiformis var. dolichophylla is located in south Florida, Cuba, and Puerto Rico, while D. filiformis can be found throughout eastern North America. As well, D. filiformis var. laeviglumis is found in New England.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

In the Coastal Plain region, Digitaria filiformis is found in pine-oak, oak-palmetto and open longleaf pine-wiregrass woodlands along with turkey-oak sand ridges, banks of ditches in saltmarshes, and transition zones between longleaf pine, turkey oak sand ridge and pine flatwoods.[5] Occasionally has been found in mesic flatwoods in Hillsborough County, Florida. [6] It has been vouchered in an outcrop habitat on Panola Mountain located within Henry-Rockdale county line, southeast of Atlanta, Georgia. [7] D.filiformis also occurs in the Kansas-Nebraska Drift Loess Hills characterized by divides with moderately steep slopes and silt loams and silty clay loam soils occasionally broken by bedrock outcrops. [8]

D. filiformis var. laeviglumis is a globally rare crabgrass endemic to to Rock Rimmon in urban Manchester, New Hampshire. This areas is characterized by an unusual temperate ridge-cliff-talus system.[9]

Disturbed habitats in the Coastal Plain region that have documented populations of D. filiformis include fallow and open weedy park fields, roadsides, powerline corridors, clobbered longleaf pine forest and cleared sand pine and pine flatwood communities.[5] D. filliformis has shown positive regrowth in reestablished longleaf pineland habitats that were disturbed by agricultural practices in South Carolina's coastal plains, making it a post-agricultural woodland indicator species.[10] D. filiformis was found to be an increaser in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances as well as in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[11]

In the Coastal Plain region it has been documented as occurring on “upland, sandhill areas on droughty, infertile entisols and ultisols with loamy sand to sandy loam surface horizons.” [12] It has also been recorded to occur in silty soils. Light levels have observed to be partially shaded.[5]

Species found associated with D. filiformis in the Coastal Plain region are Liatris, Pityopsis, Aristida stricta, Aristida purpurascens, Andropogon gerardii, Pteridium aquilinum, Nolina atopocarpa, Hedeoma graveolens, Hedyotis procumbens, Angelica dentata, Rhynchospora globularis, Solidago and Eragrostis.[5]

Phenology

General flowering time of D. filiformis is between September and October.[1] Flowering and fruiting have been observed in June, August, September, October and November.[5]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity. [13]

Seed bank and germination

A study in southwest Georgia found D. filiformis to appear in the seed bank of disturbed areas, and not native sites.[14] Seeds have also been found in seed banks that have been exposed to fire.[15]

Fire ecology

Populations of Digitaria filiformis have been known to persist through repeated annual burns,[16] and has been found in habitat types that are maintained by fire.[5]

Herbivory and toxicology

In the Kansas-Nebraska Drift Loess Hills, white-tailed deer were found to graze D. filiformis year-round.[8] Species of the Digitaria genus, including D. filiformis are considered one of the best grazing sources for cattle from April to June.[17]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

D. filiformis is listed as threatened by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Land and Forests, listed as probably extirpated by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, Natural Features Inventory, and listed as presumed extirpated by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Natural Areas and Preserves.[4]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ [[1]]GoBotany. Accessed: April 29, 2016

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 138. Print.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 2 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, H. E. Ahles, Tom Barnes, Michael B. Brooks, Robert W. Simons, Dianna Hall, R. Kral, R. K. Godfrey, Sidney McDaniel, R. A. Norris, H. R. Reed, Cecil R. Slaughter, Frankie Snow, A. E. Redford, C. Simon, A. A. Eaton, Robert L. Lazor, Bruce Hansen, JoAnn Hansen, W. A. Silveus, A. F. Clewell, Robert Blaisdell, O. Lakela, George R. Cooley, Richard J. Eaton, Daniel B. Ward, Paul O. Schallert, and A. H. Curtiss. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Brevard, Clay, Dixie, Duval, Escambia, Franklin, Flagler, Gadsden, Hillsborough, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Nassau, Osceola, Putnam, Sarasota, St. Johns, Taylor, Wakulla, and Washington. Georgia: Camden, Coffee, and Grady. Mississippi: Pearl River and Oktibbeha. North Carolina: Alexander. South Carolina: Hampton. Virginia: Pulaski. Other Countries: Switzerland.

- ↑ Myers, J. H., and Richard P. Wunderlin (2003). "Vascular Flora of Little Manatee River State Park, Hillsborough County, Florida." Castanea 68(1): 56-74.

- ↑ Bostick, P. E. (1971). "Vascular Plants of Panola Mountian, Georgia " Castanea 46(3): 194-209.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Watt, P. G., G.L. Miller, and R.J. Robel (1967). "Food Habits of White-tailed Deer in Northeastern Kansas." Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 70(2): 223-240.

- ↑ Nichols, W. F. and J. Hoy (2014). "A TEMPERATE RIDGE-CLIFF-TALUS SYSTEM IN AN URBAN SETTING: ROCK RIMMON IN MANCHESTER, NEW HAMPSHIRE." Rhodora 116(965): 83-98.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Archer, J. K., D. L. Miller, et al. (2007). "Changes in understory vegetation and soil characteristics following silvicultural activities in a southeastern mixed pine forest." Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 134: 489-504.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Andreu, M. G., et al. (2009). "Can managers bank on seed banks when restoring Pinus taeda L. plantations in Southwest Georgia?" Restoration Ecology 17: 586-596.

- ↑ Parks, G. R. (2007). Longleaf pine sandhill seed banks and seedling emergence in relation to time since fire, University of Florida. Master of Science: 84.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Rafinesque, C. S. (1828). Medical flora; or Manual of the medical botany of the United States of North America.