Dichanthelium commutatum

Common Names: variable panicgrass [1], variable witchgrass [2], Ashe's witchgrass, linear-leaved witchgrass, sprawling witchgrass[3]

| Dichanthelium commutatum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Cyperales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Genus: | Dichanthelium |

| Species: | D. communtatum |

| Binomial name | |

| Dichanthelium commutatum Schult. | |

| |

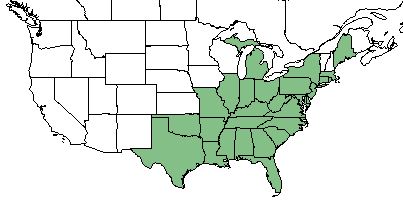

| Natural range of Dichanthelium commutatum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Dichanthelium commutatum (J.A. Shultes) Gould var. ashei (Pearson ex Ashe) Mohlenbrock; Panicum ashei Pearson ex Ashe; P. commutatum; P. commutatum var. commutatum; P. commutatum J.A. Schultes var. ashei (Pearson ex Ashe) Fernald; D. commutatum (J.A. Schultes) Gould var. commutatum; D. equilaterale (Lamson-Scribner)Wipff; P. commutatum J.A. Schultes var. joori (Vasey) Fernald; P. joorii Vasey; P. equilaterale Lamson-Scribner[3]

Varieties: D. mutabile (Lamson-Scribner & J.G. Smith ex Nash) Wipff; P. mutabile Lamson-Scribner & Smith ex Nash[3]

Description

D. communtatum is a perennial gramioid of the Poaceae family that is native to North America. [1]

Distribution

This species is found throughout the eastern United States, reaching as far west as Texas and as far north as Maine and Michigan. [1] D. commutatum var. ashei can be found from Massachusetts to Florida, Michigan, Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas, and south to Mexico. In comparison, D. commutatum var. commutatum can be found from Maine to Mexico, including Florida, Michigan, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas.[4]

Ecology

Habitat

Common habitats for D. commutatum var. commutatum include low, shaded, moist woodlands and edges of woodlands, as well as dry, thin, and rocky woods and thickets, while common habitats for D. commutatum var. ashei are sandy or dry rocky woods and openings.[4] D. commutatum has a medium tolerance for drought and shade. [1] Specimens of panicgrass have been collected in habitats that include drying loamy sand, near limestone wooded area, hardwood hammocks, longleaf pine woodland, dry sandy soil, flat oak woods, margin of field, dry banks, slash pine savanna, edge of wooded floodplain, swamp clearing, oak hammock, oak woodland, mixed hardwood forests, shaded hardwood, and swamp forests. [5] This species does not require a moist environment but it can grow in wetter condition. [1] It can also be found in large frequencies in cultivated fields.[6] As well, D. commutatum is considered an indicator species of the shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands habitat found within the Red Hills Region of north Florida and south Georgia.[7] With post agricultural succession, a study found D. commutatum to decrease in frequency in the community as years since anthropogenic disturbance increased.[8]

D. commutatum was found to be a decreaser in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances but neutral in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[9]

Associated species: Serenoa repens, Persea littoralis, Persea sp., Osmanthus megacarpa, Osmanthus sp., Morinda roic, Rapanea guianensis, Quercus geminata, Quercus laurifolia, Quercus chapmanii, Quercus sp., Panicum ravenelli, Panicum cordata, Liquidambar styraciflua, Ulmus floridana, Ulmus crassifloia, Callicarpa americana, Solanum capsicoides, Pinus taeda, Pinus palustris, Chasmanthium sp., Carya aquatica, Carya glabra, Asimina parviflora, Sabal etonia, Sabal palmetto', Parthenocissus quinquefolia, Smilax smallii, Sporobolus vaginiflorus, Stenaria nigricans, Rhynchospora divergens, Schoenus nigricans, Dichanthelium laxiflorum, D. boscii, Nyssa biflora, Fraxinus profunda, Taxodium distichum, and other grasses.[5]

Dichanthelium commutatum var. ashei is an indicator species for the North Florida Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[10]

Phenology

Generally, this species of panicgrass flowers from May until October.[4] D. commutatum has been observed flowering from March until May, with peak inflorescence in April.[11] Like other grasses, flowers of D. commutatum are commonly self-pollinated.[12]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity. [13]

Fire ecology

D. commutatum has been observed in frequently burned pine savannas,[5] with populations known to persist through repeated annual burns.[14] A study by Iglay in 2010 found that a fire treatment with the herbicide imazapyr had a positive response, increasing the frequency of D. commutatum.[15]

Herbivory and toxicology

This species consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet for large mammals, and about 10-25% of the diet for various terrestrial birds.[16]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

D. commutatum is considered endangered in the state of Illinois. [1]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 USDA Plant Database

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., et al. (2012). "Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station." Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Wilson Baker, Cecil R. Slaughter, H. Blomquist, Robert A. Norris, James P. Gillespie, H. R. Reed, R. Kral, R. Wilbur, Harry Ahles, A. Hammond, Delzie Demaree, H. Sherman, G. Carter, John W. Thierst, S. Blake, Frank Bowers, Gary Morton, Paul Hallister, Ken Rogers, r. K. Godfrey, Stanley Cain, Duane Isely, S Walsh, Dwight Isely, Sidneu McDaniel, C. Clark, W. Silveus, W. Ashe, S. Leonard, A. Radford, Randy Haynes, C. Jackson, R. L. Lazor, A. . Clewell, James . Ray Jr.., H. Kurz, Ira Wiggins, D. B. Ward, D. Burch, George Cooley, Gwynn Ramsey, R. S. Mitchell, Richard Eaton, Patricia Elliot, D.L. Martin, S. Cooper, D. Hall, Bob Simmons, Buford Pruitt, R.L. Wilbur, G. Webster, A. Curtiss, R.E. Perdue, Sid McDaniel, Bruce Hansen, JoAnn Hansen, A. G. Shuey, Gil Nelson, Marc Mino, J. M. Kane, Lisa Keppner, L. Peed, F. Sargent, R.E. Perdue, J.B. McFarlin, O. Lakela. States and counties: Florida ( Taylor, Jefferson, Jackson, Indian River, Wakulla, Thomas, Gadsden, Leon, Franklin, Walton, Madison, Volusia, Calhoun, Okaloosa, Clay, Levy, Lafayette, Escambia, Monroe, Flagler, Hernando, Suwannee, Citrus, Liberty, Bay, Marion, Nassau, Highlands, Duval, Alachua, St. John, DeSoto, Polk, Brevard, Washington, Dixie, Holmes), North Carolina (Brunswick, granville, Cumberland, Dare), Georgia (Lee, Thomas, Grady), Alabama (Geneva), Mississippi (Hancock), Louisiana (DCaldwell, Ouachita, Umiom, St. Landry, St. Mary), Virginia (Montgomery, Dickenson, Arlington, Roanoke), Arkansas (Cleburne, Stone), Alabama (De Kalb, Houston), Massachusetts, Tennessee (Bradley, Putnam, Franklin), Kentucky (Carlisle), Texas (Burleson), South Carolina (Chester), Missouir (McDonald)

- ↑ Brudvig, L. A. and E. I. Damschen (2010). "Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition." Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2013). "Prior prevalence of shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands in the Tallahassee red hills." Castanea 78(4): 266-276.

- ↑ Jenkins, M. A. and G. R. Parker (2000). "The response of herbaceous-layer vegetation to anthropogenic disturbance in intermittent stream bottomland forests of southern Indiana, USA." Plant Ecology 151: 223-237.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 21 MAY 2018

- ↑ [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 29, 2019

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Iglay, R. B., et al. (2010). "Effect of plant community composition on plant response to fire and herbicide treatments." Forest Ecology and Management 260: 543-548.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.