Desmodium ciliare

Common name: Hairy Small-leaf Ticktrefoil [1]

| Desmodium ciliare | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Genus: | Desmodium |

| Species: | D. ciliare |

| Binomial name | |

| Desmodium ciliare Muhl | |

| |

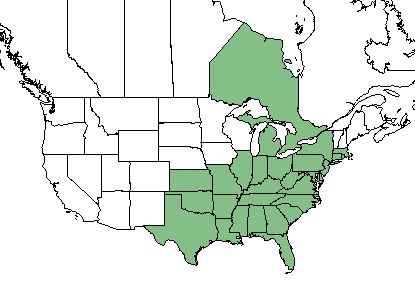

| Natural range of Desmodium ciliare from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Desmodium marilandicum (Linnaeus) A.P. de Candolle var. ciliare (Muhlenberg ex Willdenow) H. Ohashi; Meibomia ciliaris (Muhlenberg ex Willdenow) Blake[2]

Varieties: Desmodium ciliare var. lancifolium Fernald[2]

The genus name Desmodium derives from the Greek meaning of "long branch or chain".[3]

Description

D. ciliare is a perennial forb/herb of the Fabaceae family native to North America and Canada.[1] Leaves alternate, pinnately trifoliolate compound; leaflets usually 3, usually ovate-oblong or elliptic, larger ones usually less than 1.2 inches long, slightly rough to touch, stipels present; fruit is 1-3 jointed loment, margins densely covered with short, hooked hairs, surfaces moderately so.[4]

Distribution

D. ciliare can be found along the southeastern coast of the United States from Texas to Massachusetts, as well as the Ontario region of Canada.[1] It is also native to Cuba.[5]

Ecology

Habitat

D. ciliare is found in fields, woodland borders, and disturbed areas. [5] It also tends to be found in moister areas. Other native habitats include pine forests and woodlands, pine flatwoods, on limerock, slopes, and longleaf pine wiregrass communities and sand ridges. D. ciliare is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[6] A study exploring longleaf pine patch dynamics found D. ciliare to be most strongly represented within stands of longleaf pine that are between 90-130 years of age.[7]

Soils include moist loam, sandy loam, sandy clay loam, loamy sand, clay with sandstone, and other sandy soils.[8] It prefers slightly acidic to neutral soil and medium- to fine-textured soil in partial shade.[3] D. ciliare was found to have variable changes in occurrence and abundance in response to clearcutting and chopping disturbance in South Carolina. It also showed resistance to regrowth in reestablished habitat that was disturbed by these practices.[9] It became absent in response to disturbance by military training in west Georgia. It additionally showed resistance to regrowth in reestablished longleaf pine forests that were disturbed by this training.[10] D. ciliare was found to be neutral in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances as well as in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[11]

Associated species: Pinus palustris, Pinus sp., Quercus laevis, Quercus sp., Liquidambar styraciflua, Chamaecrista sp., Indigofera hirsuta, Rubus cuneifolius, Crotalaria sp., Desmodium paniculatum, Desmodium laevigatum, Desmodium lineatum, Desmodium sp., Liatris sp., and Lobelia sp.[8]

Phenology

D. ciliare has been observed to flower between September and November. [12] Otherwise, it generally flowers from June to September and fruits August to October.[5]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by translocation on animal fur or feathers.[13]

Seed bank and germination

Germination rates have been seen to decrease in burned areas rather than unburned areas. However, burning pine cones that significantly increase the heat on the soil underneath them did not affect the germination rate of D. ciliare seeds in one study.[14] Most germination appears to occur within the first year following dispersal, and seeds lack an impermeable seed coat characteristic of species capable of persisting in the seed bank.[15]

Fire ecology

This species benefits from and prefers fire disturbance.[3] Populations of Desmodium ciliare have been known to persist through repeated annual burns,[16][17] and shown to increase in frequency in response to fire disturbance.[18] Overall, flower production is seen to increase with burning regiments.[19] It has been observed in habitats that are burned annually in the winter.[8] One study found the frequency of D. ciliare to decrease in frequency in response to a spring fire, but increase in frequency in response to a summer fire.[20] However, other studies have found conflicting results of D. ciliare benefiting from different seasonality burns, and overall seems to not really be affected by fire seasonality.[19][21] A study on the environment of surface fires found germination of D. ciliare to decrease after a fire.[14]

Pollination

D. ciliare is pollinated by various members of bees in the Hymenoptera order including Bombus impatiens, B. pennsylvanicus, Megachile brevis brevis, M. mendica, M. petulans, Melissodes bimaculata bimaculata, Nomia nortoni nortoni, and Calliopsis andreniformis.[3]

Herbivory and toxicology

This species attracts birds and is a good plant for livestock grazing and browsing. The following caterpillars forage on the leaves: hoary edge (Achalarus lyciades), silver spotted skipper (Epargyreus clarus), southern cloudywing (Thorybes bathyllus), northern cloudywing (Thorybes pylades), and caterpillars of the eastern tailed blue (Everes comyntas) butterfly. The caterpillar of the gray hairstreak (Strymon melinus) butterfly feed on the flowers and developing seedpods. Other foragers include various beetles, some thirps, moth caterpillars, aphids, and stinkbugs. The seeds are eaten by bobwhite quail, turkey, white-footed mouse,and deer mouse while the foliage is eaten by larger animals including white-tailed deer and other hoofed mammal herbivores, and the cottontail rabbit.

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

D. ciliare is listed as threatened by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Land and Forests, and by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management. [1] The plant should avoid soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping and military training to conserve its presence in pine communities.[9][10] This species can be planted for longleaf restoration projects to help diversify the herbaceous layer.[22]

Cultural use

Historically, the roots were utilized the the Houma Native American tribe in Louisiana as an infusion with whiskey for treatment of weakness and cramps.[3]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 USDA Plant Database https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=DECI

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Kirk, S. and Belt, S. 2010. Plant fact sheet for Hairy Small-Leaf Ticktrefoil (Desmodium ciliare), USDANatural Resources Conservation Service, Norman A. Bern National Plant Materials Center, Beltsville, 20705.

- ↑ Gee, K. L., et al. (1994). White-tailed deer: their foods and management in the cross timbers. Ardmore, OK, Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Mugnani et al. (2019). “Longleaf Pine Patch Dynamics Influence Ground-Layer Vegetation in Old-Growth Pine Savanna”.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: R.K. Godfrey, Loran C. Anderson, V. Sullivan, J. Wooten, R. Kral, J.P. Gillespie, Andre F. Clewell, Travis MacClendon, Karen MacClendon, Bill Boothe, A.C. Matthews, C. Ritchie Bell, John W. Thieret, G.W. Parmelee, Delzie Demaree, Edward S. Steele, A.P. Anderson, Sidney McDaniel, Joel A. Barnes, Steve Cox, States and counties: Leon County Florida, Franklin County Florida, Dade County Florida, Jackson County Florida, Wakulla County Florida, Madison County Florida, Liberty County Florida, Nassau County Florida, Jefferson County Florida, Thomas County Georgia, Calhoun County Florida, Orange County North Carolina, Spartanburg County South Carolina, Acadia County Louisiana, St. Joseph County Michigan, Drew County Arkansas, Dist. of Columbia, Macon County North Carolina, Oktibbeha County Mississippi, Grenada County Mississippi, Lamar County Mississippi, Grady County Georgia, Washington County Florida, Gadsden County Florida,

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Cushwa, C.T. and M.B. Jones. (1969). Wildlife Food Plants on Chopped Areas in Piedmont South Carolina. Note SE-119. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 4 pp.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 21 MAY 2018

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Wiggers, M. S., et al. (2013). "Fine-scale variation in surface fire environment and legume germination in the longleaf pine ecosystem." Forest Ecology and Management 310: 54-63.

- ↑ • Coffey, K. L. and L. K. Kirkman (2006). "Seed germination strategies of species with restoration potential in a fire-maintained pine savanna." Natural Areas Journal 26: 289-299.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Sparks, J. C., et al. (1998). "Effects of late growing-season and late dormant-season prescribed fire on herbaceous vegetation in restored pine-grassland communities." Journal of Vegetation Science 9: 133-142.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Hiers, J. K., et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.

- ↑ Cushwa, C. T., et al. (1970). Response of legumes to prescribed burns in loblolly pine stands of the South Carolina Piedmont. Asheville, NC, USDA Forest Service, Research Note SE-140: 6.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ Dagley, C. M., et al. (2002). "Understory restoration in longleaf pine plantations: Overstory effects of competition and needlefall." Proceedings of the eleventh biennial southern silvicultural research conference.