Conradina glabra

| Conradina glabra | |

|---|---|

| |

| photo taken by Annie Schmidt | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Dicots |

| Order: | Lamiales |

| Family: | Lamiaceae |

| Genus: | Conradina |

| Species: | C. glabra |

| Binomial name | |

| Conradina glabra Shinners | |

| |

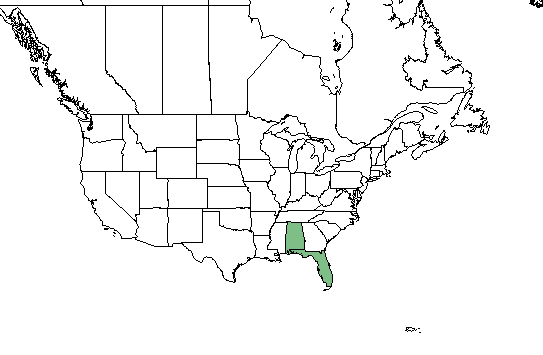

| Natural range of Conradina glabra from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Apalachicola rosemary

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

Conradina glabra is a densely branched, low shrub, usually growing less than 2.5 feet tall and possesses a strong minty odor. The leaves are evergreen, opposite, needle-like, and grow in clusters, giving the branches a bushy look. The upper surface of the leaves are smooth and hairless; however, the lower surface is covered by densely matted but nearly invisible hairs (visible with magnification). The flowers are usually in groups of 2 or 3, are 0.5 - 0.75 inches long, bent sharply upward, with the lower lip of flower three-lobed, and are white to pale lavender-pink with a band of purple dots on the white throat. The calyx is smooth or has a few short hairs.[2]

Distribution

Conradina glabra is endemic to the sandhills along the eastern shore of the Apalachicola River in Liberty county, Florida. Most populations occur on privately owned silvicultural land, the only population on public land is found at Torreya State Park.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

This species is endemic to the excessively drained sandhills east of the Apalachicola River in Liberty county, Florida. Many populations are found on privately owned land or pine plantations, the only public land with populations of C. glabra is Torreya State Park.[4][3]

Phenology

C. glabra has been observed flowering from February through July with peak inflorescence in March and April.[5] It fruits March through June.[4]

Fire ecology

Longleaf pine sandhill communities experience fire ever 1 to 10 years. Low-intensity fires have been observed to have a more positive effect on the survival of adult individuals than high intensity fires.[6]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

It is unclear of the historical range of C. glabra due to much of the land being converted to silviculture in the 1950s, before this species was discovered. Habitat modification as a result of logging, site preparation and conversion to silvicultural practices and fire suppression are the main threats to this species.[3] In 1990, a study by Gordon, transplanted populations of C. glabra from private silviculture lands to the Nature Conservancy property in Bristol, Florida. Seedling establishment was found to be high in burned areas.[6]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ [[1]]Florida Natural Areas Inventory. Accessed: April 14, 2016

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 [[2]]Accessed: April 14, 2016

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: November 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Robert K. Godfrey, N.C. Henderson, S.W. Leonard, Sidney McDaniel, Steve Orzell. States and Counties: Florida: Liberty. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 8 DEC 2016

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Gordon, D. R. (1996). "Experimental translocation of the endangered shrub Apalachicola rosemary Conradina glabra to the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve, Florida." Biological Conservation 77(1): 19-26.