Aralia spinosa

| Aralia spinosa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by James H. Miller & Ted Bodner, Southern Weed Science Society, Bugwood.org | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Apiales |

| Family: | Araliaceae |

| Genus: | Aralia |

| Species: | A. spinosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Aralia spinosa L. | |

| |

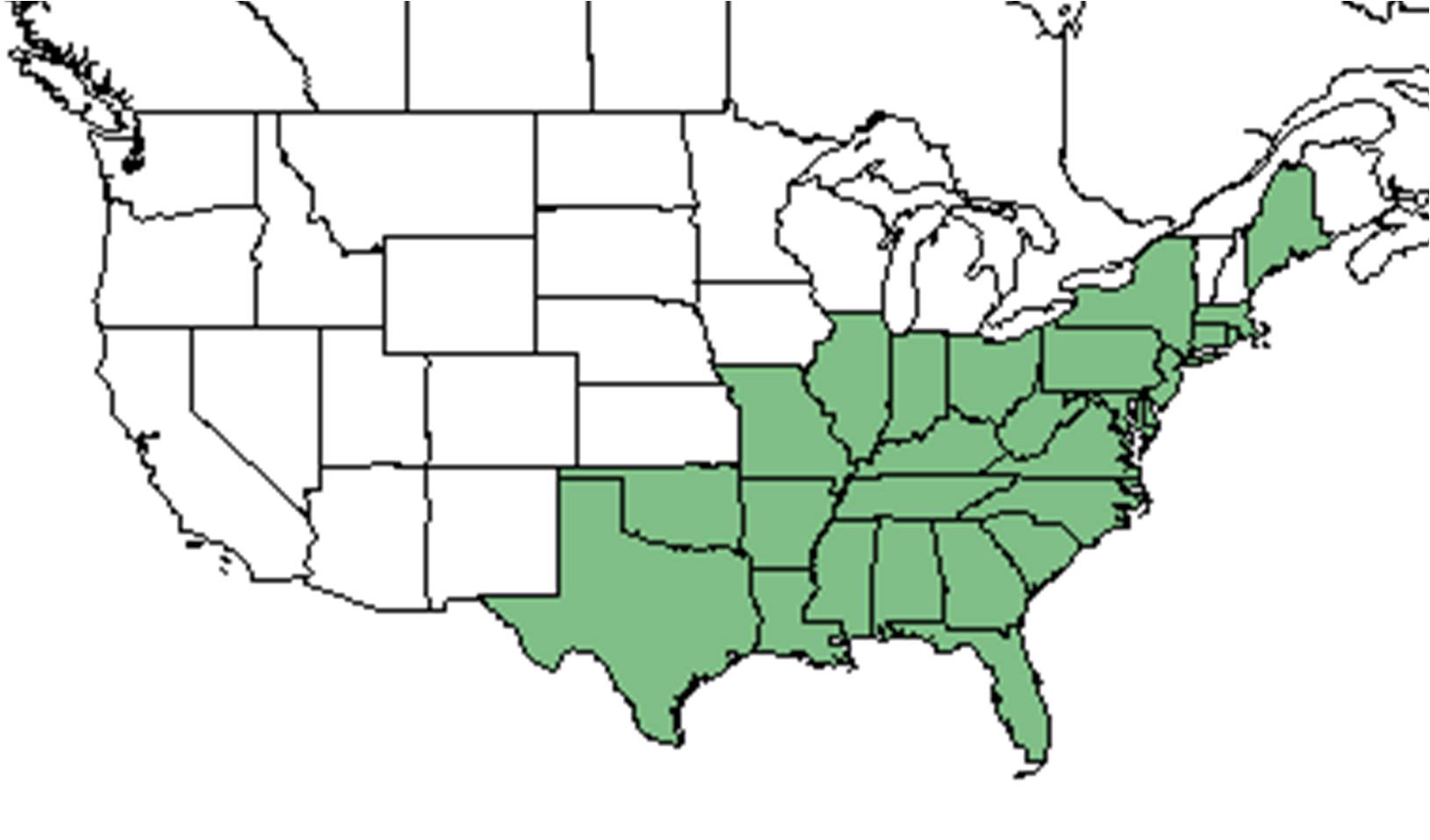

| Natural range of Aralia spinosa from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Devil's walking stick; Hercules’s-club; Prickly-ash

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

Aralia spinosa is a perennial shrub or small tree that can grow up to 8ft tall. The plant has very coarse prickly stems and decompound petiolate leaves that can be alternate or solitary. The petiolate leaflets are elliptic or ovate, grow up to 13cm long and 7cm wide, are glabrous or glabrate, acute to caudate, serrate, base oblique, rounded, or cuneate. The racemes and panicles are umbels in structure. The panicle terminal is large with the main branches growing up to 60cm long; all branches and pedicels are pubescent. There are numerous greenish to white flowers growing on pedicels 5 - 10 mm long with petals 2 -3 mm long. There are 5 stigmas that are capitate and 5 styles that are fused basally (ca. 0.5 mm) or completely separate and recurved (ca. 1 mm). The sepals are 0.4 - 0.6 mm long. The drupes are purple or black in color and are 4 - 6mm in diameter. The pyrenes are 3 - 4.5mm long.[2]

Distribution

It is found as north as New Jersey, west to Illinois, and south to Florida, and then west towards eastern Texas.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

A. spinosa has been found in mesic coastal hardwoods, the wooded slopes of broad ravine steepheads, and mesic pine-oak-hickory woods. It is also found in disturbed areas including along roadsides and annually burned savannas.[4]

Associated species include Sabal palmetto, Quercus rubra, Lirodendron tulipifera, Acer saccharum, Tsuga canadensis, Corylus americana, Carya, Quercus alba, and Fraxinus americana.[5][6]

Phenology

Aralia spinosa flowers from June to September.[3][7]

Pollination

This is one of the most, if not the most, popular flower with pollinators in the Pensacola, FL area.[8] Many species from the order Hymenoptera were observed visiting flowers of Aralia spinosa at the Archbold Biological Station.[9] These species include bees such as Epeolus zonatus (family Apidae), sweat bees such as Augochlora pura (family Halictidae), plasterer bees from the family Colletidae such as Colletes mandibularis and Hylaeus confluens, wasps from the family Leucospididae such as Leucospis robertsoni and L. slossonae, and leafcutting bees from the family Megachilidae such as Coelioxys dolichos, C. sayi, C. texana, Megachile mendica and M. xylocopoides. The leafcutting bee Coelioxys sayi (family Megachilidae) was also found to visit this species.[10]

Herbivory and toxicology

Thread-waisted wasps from the family Sphecidae such as Cerceris flavofasciata floridensis, Cerceris rufopicta, Ectemnius decemmaculatus tequesta, Ectemnius maculosus and E. rufipes ais, as well as wasps from the family Vespidae such as Euodynerus megaera, Parancistrocerus perennis anacardivora and Zethus spinipes, are known to use Aralia spinosa as a host.[10]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

The berries of Arlia spinosa are possibly poisonous if ingested in large quantities.[11] The bark and roots of the plant may cause dermatitis and blisters.[12] In Japan, the leaves of Aralia cordata are harvested before maturity, then cooked and served with vinegar. It is thought that Aralia spinosa leaves may be similarly prepared as it is very similar to the Japanese counterpart.[13]

Historically, Native Americans and African Americans used parts of the plant to treat various ailments. The bark and roots was used to make a decoction tea for blood purification and treating fevers. The roots could also be used to make a poultice that was applied to boils. Dried root powder was used for treating snakebites, and water from the roots could be used as eyedrops.[14]

Additionally the plant is used in traditional Chinese medicine possibly due its ability to lower blood sugar.[15]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 760. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Weakley, Alan S. Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States: Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina Herbarium (NCU). PDF. 1219.

- ↑ Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: May 2021. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R. Komarek, Karen MacClendon, Travis MacClendon, and Annie Schmidt. States and counties: Florida: Calhoun, Jefferson, Liberty Wakulla. Georgia: Grady.

- ↑ Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: May 2021. Collectors: Ralph L. Thompson. States and Counties: Arkansas: Craighead.

- ↑ Campbell University Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: May 2021. Collectors: E. L. Richards. States and Counties: Pennsylvania: Crawford.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 19 MAY 2021

- ↑ Observation by Shawn Stangeland in Pensacola, FL, June 25, 2017, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group June 25, 2017.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Hardin, J.W., Arena, J.M. 1969. Human Poisoning from Native and Cultivated Plants. Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina.

- ↑ Mueschner, W.C. 1957. Poisonous Plants of the United States. The Macmillan Company, New York.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.

- ↑ Burrows, G.E., Tyrl, R.J. 2001. Toxic Plants of North America. Iowa State Press.