Andropogon ternarius

| Andropogon ternarius | |

|---|---|

| |

| Andropogon ternarius taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Moncots or Dicots |

| Order: | Cyperales |

| Family: | Poaceae/Gramineae |

| Genus: | Genus |

| Species: | A. ternarius |

| Binomial name | |

| Andropogon ternarius Michx. | |

| |

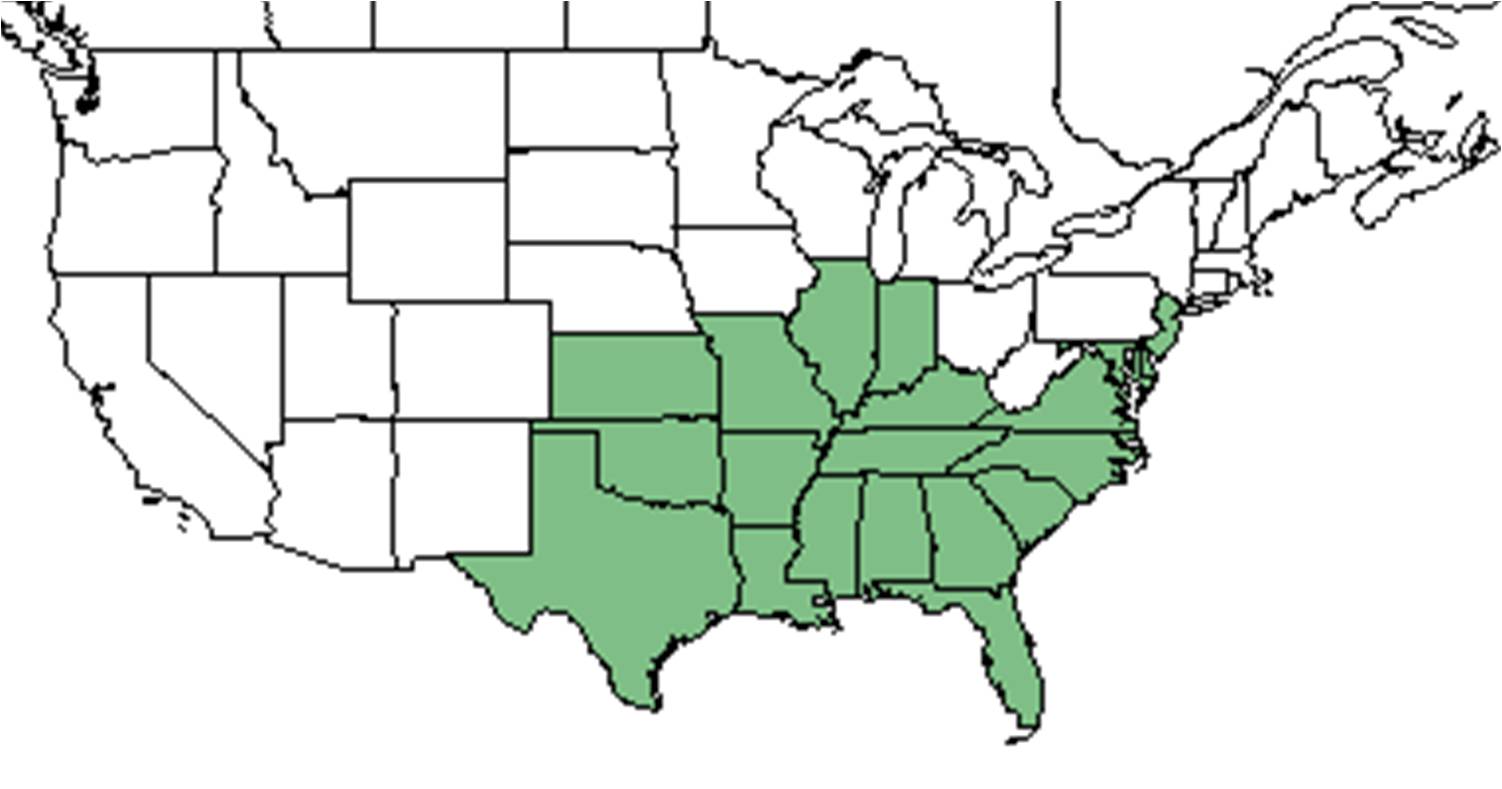

| Natural range of Andropogon ternarius from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Splitbeard bluestem

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Andropogon ternarius var. ternarius[1]

Varieties: Andropogon ternarius var. glaucescens[1]

Description

Andropogon ternarius is a perennial grass that will form mats as it grows from short hardened rhizome bases. The stems are usually greyish-green or blue in color but sometimes appear purple and grows between 0.7 - 1.5 m tall. The leaf blades grow 30 cm long and 2 - 3.5 mm wide both at the base and on the stems of the grass with a scabrous texture and pubescence on the upper surface near the ligule. The ligules are membranous, 0.5 - 1.5 mm long, and the leaf sheaths are keeled with membranous margins. There are numerous shaggy white racemes that are 1.5 - 4 cm long and join to the stem. The fertile spikelets of the plant are 5 mm long and the lemma awns are slightly twisted and 1.5 - 2.5 cm long. Sterile spikelets are equal or a little longer in length than the fertile ones. The seed grain is purplish or yellowish in color, linear ellipsoid in shape, and 2 - 3 mm long.[2]

Andropogon ternarius does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its rhizomes.[3] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an non-structural carbohydrate concentration of 26.5 mg/g (ranking 90 out of 100 species studied).

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Andropogon ternarius has rhizomes with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 0.11 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 26.5 mg g-1.[4]

Distribution

A. ternarius is native throughout the southeast United States, ranging as far as Texas and Kansas to the Midwest and the northeast up to New Jersey and Delaware. [5]

Ecology

Habitat

In the Coastal Plain in Florida and Georgia, Andropogon ternarius has been found in pine/oak sandhills, pine scrubs, turkey oak scrubs, upland pine forests, river banks, and pine flatwoods. It can occur in disturbed areas such as roadsides, recreation areas, cut-over pinewoods, gas line corridors, slash pine plantations, old fields and cultivated fields.[6] Soil types include sand, loamy sand, loam, sandy alluvium, and sandy loam.[6] Where it is found, A. ternarius is not a large portion of the graminoid plant composition or richness.[7] However, it has been identified as a disturbance indicator.[8] A. ternarius became absent in response to soil disturbance by military training in west Georgia.[9] However, it increased its frequency in response to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[10] Furthermore, A. ternarius has been found to be an increaser in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances but neutral in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[11]

Andropogon ternarius is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[12]

Associated species include Pteridium, Crataegus lacrimata, Psoralea lupinellus, Aristida purpurascens, Sorghastrum elliottii, Eragrostis hirsuta, Dichanthelium, and Muhlenbergia expansa.[6]

Phenology

Andropogon ternarius has been observed to flower and fruit May through December.[6][13]

Seed bank and germination

It has been recorded germinating in response to fire burning between the months of February to July with the most germination occurring in response to a July burn.[14]

Fire ecology

A. ternarius has been recorded in annually burned upland pines and pine savannas.[6] It has been found that Andropogon species increase in occurrence after prescribed burns in the spring,[15] and populations persist through repeated annual burns.[16][17]

It is used by birds and mammals as cover as well as the seeds as a source of food, and is grazed by cattle in the springtime shortly after growth begins.[5] A. ternarius is also utilized by native bees for nesting materials and structure.[18]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

A. ternarius is not recommended to be included in a cool season species seed mix, and is not common enough to be considered a key management species. It is known to endure periodic controlled burning regiments; annual burning followed by grazing has been found to ultimately eliminate the species from the community over time.[5] This species should avoid soil disturbance by military training to conserve its presence in pineland habitat.[9] Other suggested maintenance includes cutting back the stems in the winter once the grass has gone to seed.[18]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 162-163. Print.

- ↑ Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz-Torbio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 USDA Plants Database URL: https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=ANGE

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: October 2015. Collectors: Jame Amoroso, Loran Anderson, Wilson Baker, Kathleen Craddock Burks, A.F. Clewell, A.H. Curtiss, R. K. Godfrey, D. C. Hunt, R. Komarek, R. Kral, Karen MacClendon, Travis MacClendon, Sidney McDaniel, Marc Minno, Richard S. Mitchell, J. Roche, Cecil R. Slaughter, George Wilder, Jean W. Wooten, Bian Tan. States and Counties: Florida: Baker, Bay, Dixie, Duval, Calhoun, Columbia, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Gilchrist, Jackson, Jefferson, Lake, Leon, Liberty, Madison, Marion, Okaloosa, Taylor, Walton, Wakulla. Georgia: Grady, Thomas. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ Gilliam, F. S., et al. (2006). "Natural disturbances and the physiognomy of pine savannas: A phenomenological model." Applied Vegetation Science 9: 83-96.

- ↑ Archer, J. K., et al. (2007). "Changes in understory vegetation and soil characteristics following silvicultural activities in a southeastern mixed pine forest." Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 134: 489-504.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 7 DEC 2016

- ↑ Shepherd, B. J., et al. (2012). "Fire season effects on flowering characteristics and germination of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) savanna grasses." Restoration Ecology 20(2): 268-276.

- ↑ Haywood, J. D., et al. (1995). Responses of understory vegetation on highly erosive Louisiana soils to prescribed burning in May. Asheville, NC, USDA Forest Service, Research Note SO-383: 8.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: March 12, 2019