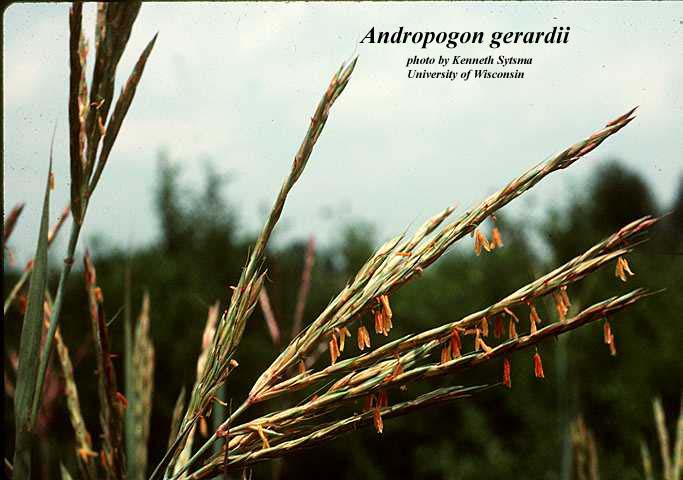

Andropogon gerardii

Common names: Big Bluestem; Turkeyfoot

| Andropogon gerardii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Tracheobionta |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Genus: | Andropogon |

| Species: | A. gerardii |

| Binomial name | |

| Andropogon gerardii Vitman | |

| |

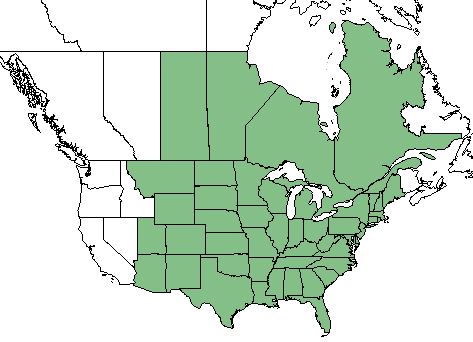

| Natural range of Andropogon gerardii from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Varieties: Andropogon gerardi Vitman; A. furcatus Muhlenbuerg ex Willdenow; A. provincialis Lamarck[1]

Synoyms: A. gerardii var. chrysocomus[1]

Description

A. gerardii is a native perennial graminoid that is a member of the Poaceae family. It is tufted, and contains short, scaly rhizomes. It is known for being a tall graminoid, ranging from 6 to 8 feet tall, and is very leafy at the basal region with some leaves that are carried up on the stem. The plant grows rhizomes that are usually 1 to 2 inches below the soil surface for clonal reproduction[2]. The seedhead is commonly branched in three parts which resembles a turkey's foot, and has a maroonish-tan color in the fall.[3]

Andropogon gerardii does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its rhizomes.[4] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an non-structural carbohydrate concentration of 35.2 mg/g (ranking 84 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 63.8% (ranking 92 out of 100 species studied).[4]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz 92021), Andropogon gerardii has rhizomes with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 0.33 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 35.2 mg g-1.[5]

Distribution

A. gerardii is distributed across the United States and Canada, but not farther west than New Mexico or Montana [2]. In Florida, A. gerardii is considered an indicator species with a restricted distribution to the western Panhandle.[6]

Ecology

Habitat

Big bluestem can be found in prairies, open woods, along riverbanks, meadows, and even roadsides. It is particularly abundant in lowland prairies and sandy areas [2] and develops best in mesic communities. [7] It is usually the dominant species within the ground community. [8] The soils within these habitats can range from sandy or loamy to clay or mesic bogs. [9] While it is most abundant in the central plains of the continental United States, it is also a component of prairies on the east coast.[3] A. gerardii has been found to be a decreaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[10]

Andropogon gerardii is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[11]

Associated species include Panicum virgatum, Schizachyrium scoparium, and Sorghastrum nutans [12]

Phenology

A. gerardii has been observed to flower from August to October with peak inflorescence in September [13].

Seed bank and germination

Seeds will usually germinate within 4 weeks when regularly irrigated [2]. It has been found to be a sizeable presence in the seed bank with large mean seed densities in sites it can be found.[14]

Fire ecology

A. gerardii tends to proliferate under frequent burning regiments[15] as seen on the Pebble Hill property.[16] The rhizomes of A. gerardii are known to resprout after a fire disturbance, and regeneration following fires is much quicker in the springtime than the summertime since the rhizomes contain winter-stores with carbohydrates [2]. As well, flowering of A. gerardii has been seen to significantly increase in late-summer fires rather than early-spring fires.[7] Due to this, it is considered a common late-season species.[8] Overall, A. gerardii abundance increases with time since the last fire.[17]

Pollination

While A. gerardii normally conducts wind pollination, it has been studied to have sex allocation that was significantly male biased.[18]

Herbivory and toxicology

A. gerardii is utilized by birds and mammals for nesting and escape cover during the summer and winter, and contributes to the spring nesting habitats since it resists lodging under snow cover [2]. It provides shelter for at least 24 songbird species as well as nesting sites for Henslow's sparrow, grasshopper sparrow and other sparrows, sedge wrens, and western meadowlarks. It also provides nesting structure and materials for native bees as well as being a larval host for the Delaware skipper and dusted skipper.[3] It is also one of the most important forage species for animals, including white-tailed deer, in the tallgrass prairie regions. [19][20]

A. geraradii provides some forage with high palatability for cattle in the early spring and summer, but cannot take too heavy of foraging use.[21]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

For management, A. gerardii has a considerably weak seedling compared to its competition, so control of its competition is necessary, such as high mowing for weed control or even grazing of competing cool season grasses before the big bluestem is 1 inch tall in the spring [2]. There are several cultivars available of A. gerardii, including 'Bison' (ND), 'Bonilla' (SD), 'Champ' (NE, IA), 'Kaw' (KS), 'Earl' (TX), 'Niagara' (NY), 'Pawnee' (NE), and 'Rountree' (IA) [2].

Cultural use

Historically, A. gerardii was used by the Omaha and Ponca tribes in Oklahoma and Nebraska to lay on the poles in order to support the earth covering of their lodges. It was also used by the Oto tribe in Missouri for general debility and languor without a known cause, and for bathing to treat fevers.[22]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 USDA Plants Database URL: https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=ANGE

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Plant database: Andropogon gerardii. (5 March 2019) Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. URL:https://www.wildflower.org/plants/search.php?search_field=&newsearch=true

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz-Torbio, M.H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Copeland, T. E., et al. (2002). "Fire season and dominance in an Illinois tallgrass prairie restoration." Restoration Ecology 10(2): 315-323.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Howe, H. F. (1995). "Succession and Fire Season In Experimental Prairie Plantings." Ecology 76(6): 1917-1925. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Howe" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Robert A. Norris, John B. Nelson, Robert K. Godfrey, R. Kral, A. F. Clewell, Gary R. Knight, Loran C. Anderson, Jean W. Wooten, S. Mitchell, Ann F. Johnson, Wilson Baker, R. Komarek, J. M. Kane, Annie Schmidt, Floyd Griffith, Cecil R. Slaughter, R. C. Kennedy, and B. Tadych. States and counties: Florida: Gulf, Liberty, Wakulla, Jefferson, Leon, Jackson, Franklin, Gadsden, Calhoun, Santa Rosa, Washington, and Nassau. Georgia: Thomas, and Grady. Missouri: Callaway.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Abrams, M. (1988). "Effects of Burning Regime on Buried Seed Banks and Canopy Coverage in a Kansas Tallgrass Prairie." The Southwestern Naturalists 33(1): 65-70.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 1 JUN 2018

- ↑ Rosburg, T. R. and M. Owens (2004). The seed bank of a reconstructed prairie. Proceeding of the North American Prairie Conferences.

- ↑ Hutchinson, T. (2005). Fire and teh herbaceous layer of eastern oak forests. F. S. United States Department of Agriculture, Northern Research Station: 136-149.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Burton, J. A. (2009). Fire frequency effects on vegetation of an upland old growth forest in eastern Oklahoma. Environmental Science. Stillwater, Oklahoma, Oklahoma State University. Bachelor: 78.

- ↑ McKone, M. J., et al. (1998). "Reproductive biology of two dominant prairie grasses (Andropogon gerardii and Sorghastrum nutans, Poaceae): Male-based sex allocation in wind-pollinated plants?" American Journal of Botany 85(6): 776-783.

- ↑ Gould, F. W. (1967). "The Grass Genus Andropogon in the United States." Brittonia 19(1): 70-76.

- ↑ Gee, K. L., et al. (1994). White-tailed deer: their foods and management in the cross timbers. Ardmore, OK, Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation.

- ↑ Byrd, Nathan A. (1980). "Forestland Grazing: A Guide For Service Foresters In The South." U.S. Department of Agriculture.

- ↑ Gilmore, M. R. (1919). Uses of plants by the indians of the Missouri River region. B. o. A. E. Smithsonian Institution. 33rd Annual Report.