Difference between revisions of "Smilax rotundifolia"

(→Taxonomic Notes) |

|||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

==Taxonomic Notes== | ==Taxonomic Notes== | ||

| + | Synonym: ''S. rotundifolia'' var. ''quadrangularis'' (Muhlenberg ex Willdenow) Wood | ||

| + | |||

==Description== <!-- Basic life history facts such as annual/perrenial, monoecious/dioecious, root morphology, seed type, etc. --> | ==Description== <!-- Basic life history facts such as annual/perrenial, monoecious/dioecious, root morphology, seed type, etc. --> | ||

''S. rotundifolia'' is a monoecious perennial that grows as a shrub or vine.<ref name ="USDA"/> | ''S. rotundifolia'' is a monoecious perennial that grows as a shrub or vine.<ref name ="USDA"/> | ||

Revision as of 15:11, 28 June 2018

| Smilax rotundifolia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Gwaltney hosted at Southeastern Flora.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Liliales |

| Family: | Smilacaceae |

| Genus: | Smilax |

| Species: | S. rotundifolia |

| Binomial name | |

| Smilax rotundifolia L. | |

| |

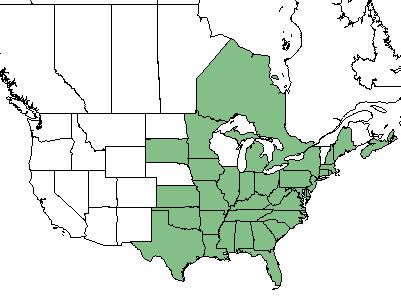

| Natural range of Smilax rotundifolia from USDA NRCS [1]. | |

Common Names: Common greenbriar; bullbriar; horsebriar;[1] roundleaf greenbrier[2]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonym: S. rotundifolia var. quadrangularis (Muhlenberg ex Willdenow) Wood

Description

S. rotundifolia is a monoecious perennial that grows as a shrub or vine.[2]

Distribution

The distribution of S. rotundifolia ranges from eastern Texas, westward to northern Florida, and northward into the provinces of Nova Scotia and Ontario Canada.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

S. rotundifolia is found in a variety of upland and wetland habitats.[1]

Phenology

In the southeastern and mid-Atlantic United States, S. rotundifolia flowers from April through May with fruiting occurring in September through November and persisting beyond.[1]

Fire ecology

Controlled burns conducted during the spring of 2001 and 2004 in an Ohio mixed-oak hardwood forest had the fire spread at mean rates of 6.2-11.3 m min-1 (as cited in [3]). These burns significantly reduced the mean percent cover of S. rotundifolia from 10.9% in 2001 and 8.1% in 2004 to 0.7 and 1.1%, respectively. The combination of burn and winter thinning yielded similar results producing mean coverage of 0.7 and 1.9% for 2001 and 2004, respectively.[3] Burns also increase the level of crude protein in S. rotundifolia,[4] which may alter browsing pressure. In the white pine and white pine-hardwood forests of New Hampshire, low intensity spring and fall fires top kill S. rotundifolia. Following these burns, S. rotundifolia vigorously reappears through vegetative reproduction.[5]

Pollination

The pollen of S. rotundifolia is linked via viscin threads that prevent it from being wind dispersed; instead, it relies on insects for pollination.[6]

Use by animals

Smilax rotundifolia comprises 5-10% of the diet of several large mammals, small mammals, and terrestrial birds.[7] Leave and twigs of S. rotundifolia are known to have been consumed by the Florida marsh rabbit (Sylvilagus palustris paludicola).[8]

Conservation and Management

Winter thinning in an Ohio mixed-oak hardwood forest reduced the mean percent coverage of S. rotundifolia from 10.9% to 3.1%. This reduced value was still higher than the reduction of cover produced by burning, suggesting burning to be more effective in reducing the coverage of S. rotundifolia.[3]

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Weakley AS (2015) Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 USDA NRCS (2016) The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 23 January 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Albrecht MA, McCarthy BC (2006) Effects of prescribed fire and thinning on tree recruitment patterns in central hardwood forests. Forest Ecology and Management 226:88-103.

- ↑ DeWitt JB, Derby, JV Jr. (1955) Changes in nutritive value of browse plants following forest fires. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 19(1)65-70.

- ↑ Chapman RR, Crow GE (1981) Application of Raunkiaer's life form system to plant species survival after fire. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 108(4):472-478.

- ↑ Kevan PG, Ambrose JD, Kemp JR (1991) Pollination in an understory vine, Smilax rotundifolia, a threatened plant of the Carolinian forests in Canada. Canadian Journal of Botany 69:2555-2559.

- ↑ Miller JH, Miller KV (1999) Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Blair WF (1936) The Florida marsh rabbit. Journal of Mammalogy 17(3):197-207.