Difference between revisions of "Rubus cuneifolius"

Krobertson (talk | contribs) |

Krobertson (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

===Phenology===<!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ===Phenology===<!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ||

| − | Flowering occurs between March and June, peaking in April,<ref name="Weakley 2015"/><ref>Nelson G. (6 December 2017) PanFlora. Retrieved from gilnelson.com/PanFlora/</ref> with fruiting occurring from May through July.<ref name="Skeate 1987">Skeate S. T. (1987). Interactions between birds and fruits in a northern Florida hammock community. Ecology 68(2):297-309.</ref> ''R. cuneifolius'' produces a white conspicuous flower.<ref name="Ladybird"/> The timing of flowering has been shown to be sensitive to ozone levels where elevated levels cause earlier flowering but produce fewer large ripe fruits.<ref name="Chappelka 2002"/> Standing crops of fruit in Georgia flatwoods peaked at 114.5 g Dm<sup>-2</sup> with 52% of plots containing fruit in 5 year old plantations.<ref>Johnson A. S. and Landers J. L (1978). Fruit production in slash pine plantations in Georgia. The Journal of Wildlife Management 42(3):606-613.</ref> | + | Flowering occurs between March and June, peaking in April,<ref name="Weakley 2015"/><ref>Nelson G. (6 December 2017) PanFlora. Retrieved from gilnelson.com/PanFlora/</ref> with fruiting occurring from May through July.<ref name="Skeate 1987">Skeate S. T. (1987). Interactions between birds and fruits in a northern Florida hammock community. Ecology 68(2):297-309.</ref> ''R. cuneifolius'' produces a white conspicuous flower.<ref name="Ladybird"/> The timing of flowering has been shown to be sensitive to ozone levels where elevated levels cause earlier flowering but produce fewer large ripe fruits.<ref name="Chappelka 2002"/> Standing crops of fruit in Georgia flatwoods peaked at 114.5 g Dm<sup>-2</sup> with 52% of plots containing fruit in 5 year old plantations.<ref>Johnson A. S. and Landers J. L (1978). Fruit production in slash pine plantations in Georgia. The Journal of Wildlife Management 42(3):606-613.</ref> It typically does not flower and fruit until the second year following fire.<ref>Robertson, K.M. 2017. Personal observation at Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, Florida.</ref> |

===Seed dispersal=== | ===Seed dispersal=== | ||

Revision as of 12:43, 22 January 2018

| Rubus cuneifolius | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Robert H. Mohlenbrock hosted at USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae - Rose family |

| Genus: | Rubus - blackberry |

| Species: | R. cuneifolius |

| Binomial name | |

| Rubus cuneifolius Pursh | |

| |

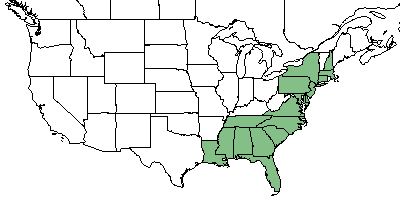

| Natural range of Rubus cuneifolius from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common Name(s): sand blackberry[1][2], sand bramble, wedge sand blackberry[2]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Varieties: R. cuneifolius var. angustior; R. cuneifolius var. subellipticus; R. cuneifolius var. spiniceps[2]

Synonyms: R. chapmannii; R. dixiensis

Description

Rubus cuneifolius is a dioecious perennial subshrub.[2]

Distribution

R. cuneifolius is found primarily on the coastal plains from Connecticut and New York south to Florida, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana.[1][2]

Ecology

Habitat

R. cuneifolius commonly inhabits woodlands, forests, and disturbed areas.[1] This includes early successional areas.[3] It uses a medium amount of water, occurs in full sunlight to partial shade, and has a medium tolerance to calcium carbonate.[4] A study in the Great Dismal Swamp, Virginia, found R. cuneiolius was present in uncut-burned areas with a mean biomass of 1.16 g m-2 yr-1.[5]

Phenology

Flowering occurs between March and June, peaking in April,[1][6] with fruiting occurring from May through July.[7] R. cuneifolius produces a white conspicuous flower.[4] The timing of flowering has been shown to be sensitive to ozone levels where elevated levels cause earlier flowering but produce fewer large ripe fruits.[3] Standing crops of fruit in Georgia flatwoods peaked at 114.5 g Dm-2 with 52% of plots containing fruit in 5 year old plantations.[8] It typically does not flower and fruit until the second year following fire.[9]

Seed dispersal

Seeds of R. cuneifolius are likely primarily dispersed by vertebrates, such as migrating birds and deer, which consume the fruits.[10]

Seed bank and germination

Seeds of R. cuneifolius were commonly observed in Georgia seed banks of longleaf pine - wiregrass - bracken fern forests maintained by annual spring burns since 1961.[11] Annual disking of fallow fields in different months also did not affect the presence of Rubus cuneifolius suggesting an abundance of seeds in the seed bank.[12]

Fire ecology

R. cuneifolius is not considered a fire tolerant species. However, it is often found in burned areas taking advantage of its abundance in the seed bank[11] and refuge in unburned thickets. It is also worth noting, that the removal of fire from old-field pineland for 44 years did not produce an increase in R. cuneifolius frequency, but rather a decrease from 80 individual in 1966 to 69 in 2013.[13]

Pollination

R. cuneifolius is recognized to attract a large number of native bees for pollination.[4]

Use by animals

Berries produced by R. cuneifolius are highly palatable by browsing animals, composing 10-25% of the diet for many species of terrestrial birds, large mammals and small mammals. It is also an occasional source of cover for small mammals and terrestrial birds.[2] Because R. cuneifolius fruits in the late summer, it is likely an important source of energy for fall migrating bird species.[7] Besides attracting pollinators, R. cuneifolius is known for providing nesting materials/structure for native bees.[4]

Diseases and parasites

R. cuneifolius hosts several species of thripes (Frankliniella spp.) which are tiny insects (1 mm or less) that feed on new plant growth producing cosmetic damage and sometimes transmitting diseases to the plant.[14]

Conservation and Management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Weakley A. S.(2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 30 November 2017). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Chappelka A. H. (2002). Reproductive development of blackberry (Rubus cuneifolius), as influenced by ozone. New Phytologist 155-249-255.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Plant database: Rubus cunifolius. (11 December 2017).Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. URL: https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=RUCU

- ↑ McKinley C. E. and Day, Jr. F. P. (1979). Herbaceous production in cut-burned, uncut-burned, and control areas of a Chamaecyparis thyoides (L.) BSP (Cupressaceae) stand in the Great Dismal Swamps. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 106(1):20-28.

- ↑ Nelson G. (6 December 2017) PanFlora. Retrieved from gilnelson.com/PanFlora/

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Skeate S. T. (1987). Interactions between birds and fruits in a northern Florida hammock community. Ecology 68(2):297-309.

- ↑ Johnson A. S. and Landers J. L (1978). Fruit production in slash pine plantations in Georgia. The Journal of Wildlife Management 42(3):606-613.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. 2017. Personal observation at Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, Florida.

- ↑ White D. W. and Stiles E. W. (1992). Bird dispersal of fruits of species introduced into eastern North America. Canadian Journal of Botany 70(8):1689-1696.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Buckner J. L. and Landers J. L. (1979). Fire and disking effects on herbaceous food plants and seed supplies. The Journal of Wildlife Management 43(3):807-811.

- ↑ Kay C. A. R., Clewell A. F., and Ashler E. W. (1978). Vegetative cover in a fallow field: Responses to season of soil disturbance. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 105(2):143-147.

- ↑ Clewell A. F. (2014). Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida. Castanea 79(3):147-167.

- ↑ Chellemi D. O., Funderburk J. E., and Hall D. W. (1994). Seasonal abundance of flower-inhabiting Frankliniella species (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) on wild plant species. Environmental Entomology 23(2):377-342.