Morella cerifera

| Morella cerfiera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Karan A. Rawlins, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Tracheophyta- Vascular plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Myricaceae |

| Genus: | Morella |

| Species: | M. cerfiera |

| Binomial name | |

| Morella cerfiera (L.) Small | |

| |

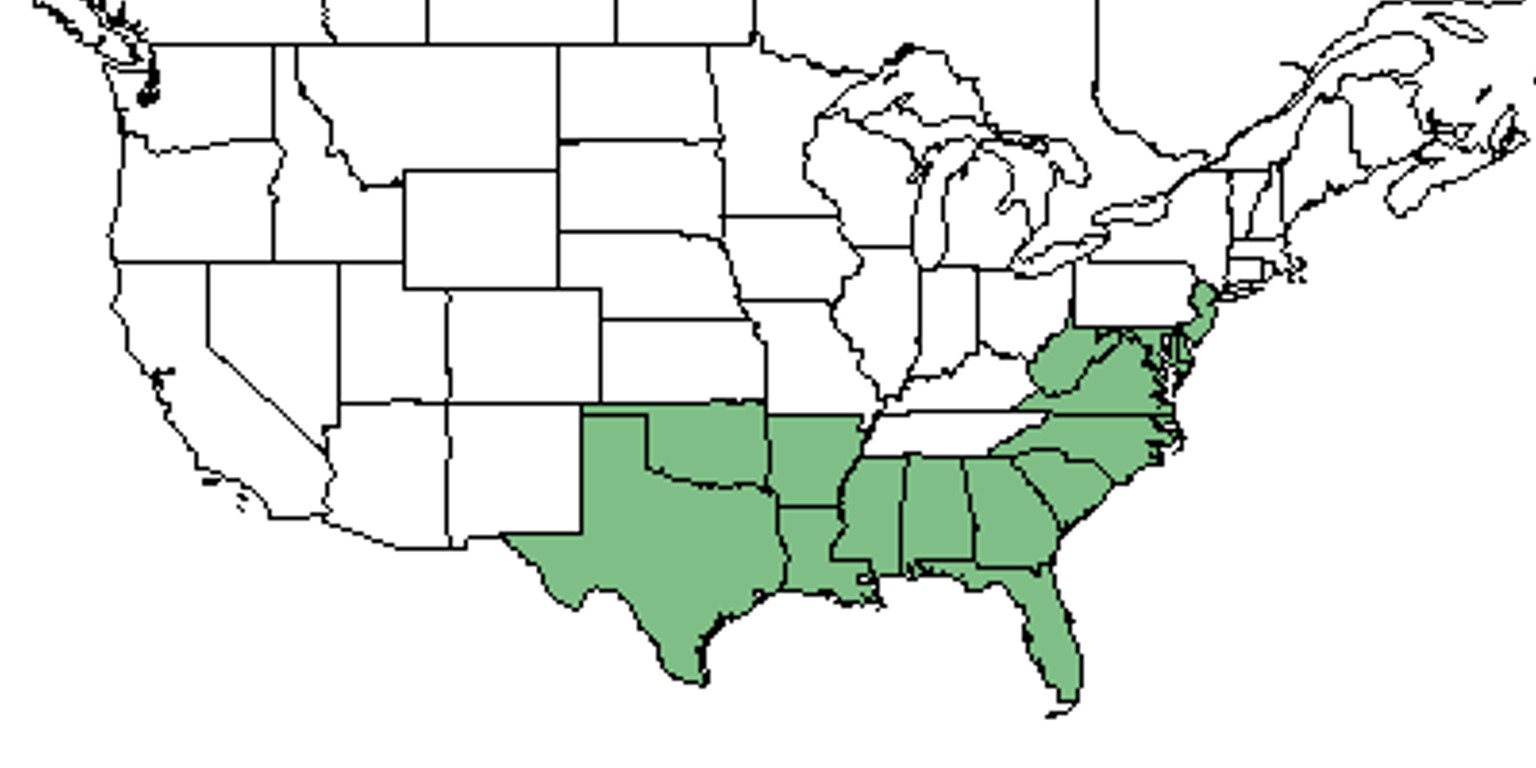

| Natural range of Morella cerfiera from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: common wax-myrtle, southern bayberry

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Myrica cerifera; Myrica cerifera Linnaeus var. cerifera; Cerothamnus ceriferus (Linnaeus) Small[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

"Dioecious or monoecious shrubs or small trees, with brown to brownish-black, pubescent to glabrate twigs. Leaves deciduous or semi-evergreen, coriaceous, petiolate, exstipulate. Staminate catkins ovoid-cylindric, 0.6-2 cm long, 4-6 mm in diam.; bracteate and bracteolate; stamens 2-1, mostly 2-5. Pistillate catkins ovoid or cylindric, 5-10 mm long, deciduous-bracteate. Fruits drupaceous, white, globose, verrucose, 2.5-7 mm in diam. A taxonomically difficult group with intergrading species."[2]

"Shrub or small tree, 0.3-7 m tall. Leaves oblanceolate or elliptic, to 8 cm long and 2cm wide, heavily resinous on both surfaces, usually pubescent beneath, acute or obtuse, serrate or entire, base cuneate to attenuate, petioles to 1 cm long. Fruits 2.5-3.5 mm in diam."[2]

Distribution

Is found within the Coastal Plain and as far north as New Jersey.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

The species is naturally found in interdune swales, pocosins, brackish marshes, and other wet to moist habitats.[1]

M. cerifera has been found in sand barrens, mesic pine hardwood forests, turpentine glades, dry sandstone glades, pond edges, pineland bogs, pine flatwoods, maritime forests, and swamps.[3][4][5][6] It is also found in disturbed areas including highway roadsides, disturbed wetland edges, and disturbed post oak savannah.[4][5][7]

M. cerifera has shown regrowth in response to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina Coastal Plain communities, making it an indicator species for post-agricultural woodlands.[8] M. cerifera reduced its crown cover and biomass in response to heavy silviculture in north Florida.[9] It decreased its cover in response to clearcutting and chopping in north Florida flatwoods.[10] It also decreased its frequency in response to roller chopping in east Texas pinewoods.[11] This species has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished native habitats that were disturbed by these practices.[9][10][11] M. cerifera had mixed responses to clearcutting and roller chopping in north Florida and to KG blade disturbance in east Texas.[12][11] Its foliar cover is sometimes dependent on time since disturbance in north Florida flatwoods. In Texas pinewoods, the species typically decreased in frequency or was unaffected by KG blade disturbance.[12][11]

Morella cerifera is frequent and abundant in the Calcareous Savannas community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[13]

Phenology

This species flowers in April and fruits from August to October.[1]

Fire ecology

Populations of Morella cerifera have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[14][15][16]

Herbivory and toxicology

Morella cerifera has been observed to host plant bugs such as Psallus variabilis (family Miridae), and leafhoppers from the Cicadellidae family such as Empoasca deckeri and Empoasca fabae.[17]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

The wax from this plant can be used to make candles, and the leaves and berries can act as a substitute for bay leaves in food.[18]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 360. Print.

- ↑ Albion College accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: NA. States and Counties: North Carolina: Brunswick.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Angelo State University Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Paul A. Fryxell, Jeff Harper, and Stanely D. Jones, and Robert Kral. States and Counties: Florida: Pasco. Georgia: Ben Hill. Louisiana: Natchitoches. Texas: Aransas, Brazos, and Hardin.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Arizona State University Vascular Plant Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: W.R. Faircloth and A.E. Radford. States and Counties: Georgia: Brooks. South Carolina: Orangeburg.

- ↑ Catawba College Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: D. Reyes. States and Counties: North Carolina: Carteret.

- ↑ Colorado State University, Charles Maurer Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Raul Gutierrez Juanita Alejandro. States and Counties: Florida: Hillsborough.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Conde, L.F., B.F. Swindel, and J.E. Smith. (1986). Five Years of Vegetation Changes Following Conversion of Pine Flatwoods to Pinus elliottii Plantations. Forest Ecology and Management 15(4):295-300.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Stransky, J.J., J.C. Huntley, and Wanda J. Risner. (1986). Net Community Production Dynamics in the Herb-Shrub Stratum of a Loblolly Pine-Hardwood Forest: Effects of CLearcutting and Site Preparation. Gen. Tech. Rep. SO-61. New Orleans, LA: U.S. Dept of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Forest Experiment Station. 11 p.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Lewis, C.E., G.W. Tanner, and W.S. Terry. (1988). Plant responses to pine management and deferred-rotation grazing in north Florida. Journal of Range Management 41(6):460-465.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.