Difference between revisions of "Mimosa quadrivalvis"

Lsandstrum (talk | contribs) |

Emmazeitler (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | Common name: | + | Common name: Florida sensitive-briar<ref name="weakley">Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.</ref> |

==Taxonomic notes== | ==Taxonomic notes== | ||

| − | Synonyms: ''Leptoglottis | + | Synonyms: ''Leptoglottis floridana'' (Chapman) Small ex Britton & Rose; ''Schrankia microphylla'' (Dryander) J.F. MacBride ''var. floridana'' (Chapman) Isely.<ref name="weakley">Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.</ref> |

| − | + | Varieties: ''Mimosa quadrivalvis'' Linnaeus var. ''floridana'' (Chapman) Barneby.<ref name="weakley">Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.</ref> | |

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

<!-- Basic life history facts such as annual/perrenial, monoecious/dioecious, root morphology, seed type, etc. --> | <!-- Basic life history facts such as annual/perrenial, monoecious/dioecious, root morphology, seed type, etc. --> | ||

| + | ''M. quadrivalvis'' is an armed sprawling vine with 3-5 pinnae pairs per leaf and leaflets with evident secondary veins.<ref name="weakley">Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.</ref> | ||

| − | This species is frequent where it is found and has a sprawling behavior. <ref name="FSU Herbarium">Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: [http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu]. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Edwin L. Tyson, J. Dwyer, Kurt Blum, Robert L. Lazor, Loran C. Anderson, J, Craddock Burks, Grady W. Reinert, R.C. Phillips, Gary R. Knight, Norlan C. Henderson, R. Kral, A.F. Clewell, Robert K. Godfrey, William Reese, Paul Redfearn, J.P. Gillespie, Nancy Caswell, Richard S. Mitchell, Patricia Elliot, Gwynn W. Ramsey, D. B. Ward, S. S. Ward, D.S. Correll, Robert J. Lemaire, L.S. Beard, R.O. Vail, W.B. Fox, Edward E. Terrell, S.B. Jones, Sidney McDaniel, V.L. Cory, Brunelle Moon, Cecil R. Slaughter, Robert R. Simons, Angus Gholson, Walter S. Judd, Bob Simons, Tom Morris, William Lindsey, Elmer C. Prichard, L.J. Brass, O. Lakela, John W. Thieret, Gerardo Garcia, Anastacio Bernal, Natalio Castillo, Guillermo Perez, Nick Lopez, W. L. McCart, D. S. Correll, I. M. Johnston, Duane Isely, F. L. Lewton, H. R. Reed, L. S. Beard, and R O Vail. States and Counties: Florida: Calhoun, Citrus, Duval, Franklin, Gadsden, Highlands, Indian River, Jackson, Lake, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Marion, Nassau, Osceola, Pinellas, Polk, Suwannee, Taylor, Wakulla, Walton, and Volusia. Georgia: Seminole, and Thomas. Arkansas: Clark and Washington. North Carolina: Robeson and Rockingham. Alabama: Pickens and Sumter. Louisiana: Acadia. Texas: Andrews,Aransas, Callahan, Comal, Dallas, Denton, Dimmit, Ft. McKanepp, Haskell, Leon, Sutton, Taylor, Van Zandt, and Zapata. Kansas: Franklin. Missouri: Bates and Greene. Countries: Panama.</ref> It is a vining plant that creeps and crawls as well. <ref name="FSU Herbarium"/> | + | This species is frequent where it is found and has a sprawling behavior.<ref name="FSU Herbarium">Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: [http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu]. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Edwin L. Tyson, J. Dwyer, Kurt Blum, Robert L. Lazor, Loran C. Anderson, J, Craddock Burks, Grady W. Reinert, R.C. Phillips, Gary R. Knight, Norlan C. Henderson, R. Kral, A.F. Clewell, Robert K. Godfrey, William Reese, Paul Redfearn, J.P. Gillespie, Nancy Caswell, Richard S. Mitchell, Patricia Elliot, Gwynn W. Ramsey, D. B. Ward, S. S. Ward, D.S. Correll, Robert J. Lemaire, L.S. Beard, R.O. Vail, W.B. Fox, Edward E. Terrell, S.B. Jones, Sidney McDaniel, V.L. Cory, Brunelle Moon, Cecil R. Slaughter, Robert R. Simons, Angus Gholson, Walter S. Judd, Bob Simons, Tom Morris, William Lindsey, Elmer C. Prichard, L.J. Brass, O. Lakela, John W. Thieret, Gerardo Garcia, Anastacio Bernal, Natalio Castillo, Guillermo Perez, Nick Lopez, W. L. McCart, D. S. Correll, I. M. Johnston, Duane Isely, F. L. Lewton, H. R. Reed, L. S. Beard, and R O Vail. States and Counties: Florida: Calhoun, Citrus, Duval, Franklin, Gadsden, Highlands, Indian River, Jackson, Lake, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Marion, Nassau, Osceola, Pinellas, Polk, Suwannee, Taylor, Wakulla, Walton, and Volusia. Georgia: Seminole, and Thomas. Arkansas: Clark and Washington. North Carolina: Robeson and Rockingham. Alabama: Pickens and Sumter. Louisiana: Acadia. Texas: Andrews,Aransas, Callahan, Comal, Dallas, Denton, Dimmit, Ft. McKanepp, Haskell, Leon, Sutton, Taylor, Van Zandt, and Zapata. Kansas: Franklin. Missouri: Bates and Greene. Countries: Panama.</ref> It is a vining plant that creeps and crawls as well.<ref name="FSU Herbarium"/> |

==Distribution== | ==Distribution== | ||

| + | This species is a southeastern Coastal Plain endemic, ranging from Georgia to Florida.<ref name="weakley">Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.</ref> | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

In a study comparing N2 fixation potential in nine legume species occurring in longleaf pine-wiregrass ecosystems, ''M. quadrivalvis'' showed clear superiority in growing a large nodule mass to support the high N2 fixation activity.<ref name=cat>Cathey, S. E., L. R. Boring, et al. (2010). "Assessment of N2 fixation capability of native legumes from the longleaf pine-wiregrass ecosystem." Environmental and Experimental Botany 67: 444-450.</ref> Aboveground N concentration was the greatest for ''M. quadrivalis'' species.<ref name=cat/> N2 fixation potential for ''M. quadrivalvis'' does not differ between shaded and unshaded environments.<ref name=cat/> The high potential for N2 fixation makes ''M. quadrivalvis'' a candidate species for contributing to the N economy in the restoration of longleaf pine ecosystems.<ref name=cat/> | In a study comparing N2 fixation potential in nine legume species occurring in longleaf pine-wiregrass ecosystems, ''M. quadrivalvis'' showed clear superiority in growing a large nodule mass to support the high N2 fixation activity.<ref name=cat>Cathey, S. E., L. R. Boring, et al. (2010). "Assessment of N2 fixation capability of native legumes from the longleaf pine-wiregrass ecosystem." Environmental and Experimental Botany 67: 444-450.</ref> Aboveground N concentration was the greatest for ''M. quadrivalis'' species.<ref name=cat/> N2 fixation potential for ''M. quadrivalvis'' does not differ between shaded and unshaded environments.<ref name=cat/> The high potential for N2 fixation makes ''M. quadrivalvis'' a candidate species for contributing to the N economy in the restoration of longleaf pine ecosystems.<ref name=cat/> | ||

===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| − | This species has been found in open pinewoods, oak-scrub woodlands, prairies, limestone glades, deciduous forests, turkey oak-pinelands, savannas, well drained ridges, ungrazed native grasslands, arroyos, and bare chalk areas. <ref name="FSU Herbarium"/> It is commonly found in pine sandhill environments. <ref name=dow> Downer, M. R. (2012). Plant species richness and species area relationships in a Florida sandhill community. Integrative Biology. Ann Arbor, MI, University of South Florida. M.S.: 52. </ref> Occurs in areas that have sandy loam, peat, gravel, and/or clay loam that is dry, loose, or moist.<ref name=mil>Miller, J. H., R. S. Boyd, et al. (1999). "Floristic diversity, stand structure, and composition 11 years after herbicide site preparation." Canadian Journal of Forest Research 29: 1073-1083.</ref> <ref name="FSU Herbarium"/> ''Mimosa quadrivalvis'' is predominately in native groundcover with a statistical affinity in upland pinelands of South Georgia.<ref name=ost> Ostertag, T.E., and K.M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Pages 109–120 in R.E. Masters and K.E.M. Galley (eds.). Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems.</ref> This species can be found growing in open to semi-shaded areas. <ref name="FSU Herbarium"/> ''M. quadrivalvis'' responds negatively to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plain communities. This marks it as an indicator species for remnant woodland.<ref>Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.</ref> It also responds positively to disking in Southern Georgia, especially in double-disked plots where its density was highest.<ref>Buckner, J.L. and J.L. Landers. (1979). Fire and Disking Effects on Herbaceous Food Plants and Seed Supplies. The Journal of Wildlife Management 43(3):807-811.</ref> When exposed to soil disturbance by military training in West Georgia, ''M. quadrivalvis'' responds negatively by way of absence.<ref>Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.</ref> It also responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in Southwest Georgia.<ref>Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.</ref> | + | This species has been found in open pinewoods, oak-scrub woodlands, prairies, limestone glades, deciduous forests, turkey oak-pinelands, savannas, well drained ridges, ungrazed native grasslands, arroyos, and bare chalk areas.<ref name="FSU Herbarium"/> It is commonly found in pine sandhill environments.<ref name=dow> Downer, M. R. (2012). Plant species richness and species area relationships in a Florida sandhill community. Integrative Biology. Ann Arbor, MI, University of South Florida. M.S.: 52. </ref> Occurs in areas that have sandy loam, peat, gravel, and/or clay loam that is dry, loose, or moist.<ref name=mil>Miller, J. H., R. S. Boyd, et al. (1999). "Floristic diversity, stand structure, and composition 11 years after herbicide site preparation." Canadian Journal of Forest Research 29: 1073-1083.</ref><ref name="FSU Herbarium"/> ''Mimosa quadrivalvis'' is predominately in native groundcover with a statistical affinity in upland pinelands of South Georgia.<ref name=ost> Ostertag, T.E., and K.M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Pages 109–120 in R.E. Masters and K.E.M. Galley (eds.). Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems.</ref> This species can be found growing in open to semi-shaded areas.<ref name="FSU Herbarium"/> ''M. quadrivalvis'' responds negatively to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plain communities. This marks it as an indicator species for remnant woodland.<ref>Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.</ref> It also responds positively to disking in Southern Georgia, especially in double-disked plots where its density was highest.<ref>Buckner, J.L. and J.L. Landers. (1979). Fire and Disking Effects on Herbaceous Food Plants and Seed Supplies. The Journal of Wildlife Management 43(3):807-811.</ref> When exposed to soil disturbance by military training in West Georgia, ''M. quadrivalvis'' responds negatively by way of absence.<ref>Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.</ref> It also responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in Southwest Georgia.<ref>Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.</ref> |

| − | Associated species include ''Pinus palutris, Quercus laevis, Muhlenbergia, Aristida longespica, A. oligantha, Juniperus, Chamaecyparis, Sabal, Magnolia, Acer, Illicium, Salix, Asclepias curtissii, Palafoxia, Paroncyhia, Quercus myrtifolia, Q. geminata,'' and ''Serenoa repens''. <ref name="FSU Herbarium"/> | + | Associated species include ''Pinus palutris, Quercus laevis, Muhlenbergia, Aristida longespica, A. oligantha, Juniperus, Chamaecyparis, Sabal, Magnolia, Acer, Illicium, Salix, Asclepias curtissii, Palafoxia, Paroncyhia, Quercus myrtifolia, Q. geminata,'' and ''Serenoa repens''.<ref name="FSU Herbarium"/> |

===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ||

| − | This species has been observed flowering in February as well as April through September and fruiting from April through September. <ref name="FSU Herbarium"/> | + | This species has been observed flowering in February as well as April through September and fruiting from April through September.<ref name="FSU Herbarium"/> |

===Seed dispersal=== | ===Seed dispersal=== | ||

| − | This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity. <ref>Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.</ref> | + | This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.<ref>Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.</ref><ref name=maz> Maza-Villalobos, S., C. Lemus-Herrera, et al. (2011). "Successional trends in soil seed banks of abandoned pastures of a Neotropical dry region." Journal of Tropical Ecology 27: 35-49. </ref> |

===Seed bank and germination=== | ===Seed bank and germination=== | ||

| − | Seed coats are hard and viable seed can persist in the seed bank for at least two years. <ref> Coffey, K. L. and L. K. Kirkman (2006). "Seed germination strategies of species with restoration potential in a fire-maintained pine savanna." Natural Areas Journal 26: 289-299. </ref> | + | Seed coats are hard and viable seed can persist in the seed bank for at least two years.<ref> Coffey, K. L. and L. K. Kirkman (2006). "Seed germination strategies of species with restoration potential in a fire-maintained pine savanna." Natural Areas Journal 26: 289-299. </ref> |

===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

| − | This species has been found in areas that are burned. <ref name="FSU Herbarium"/> | + | This species has been found in areas that are burned.<ref name="FSU Herbarium"/> |

===Pollination=== | ===Pollination=== | ||

| − | The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of ''Mimosa quadrivalvis'' var. ''angustata'' at Archbold Biological Station: <ref name="Deyrup 2015">Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.</ref> | + | The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of ''Mimosa quadrivalvis'' var. ''angustata'' at Archbold Biological Station:<ref name="Deyrup 2015">Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.</ref> |

Colletidae: ''Colletes distinctus'' | Colletidae: ''Colletes distinctus'' | ||

Revision as of 12:02, 28 September 2020

| Mimosa quadrivalvis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo take by Michelle M. Smith | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Mimosa |

| Species: | M. quadrivalvis |

| Binomial name | |

| Mimosa quadrivalvis L. | |

| |

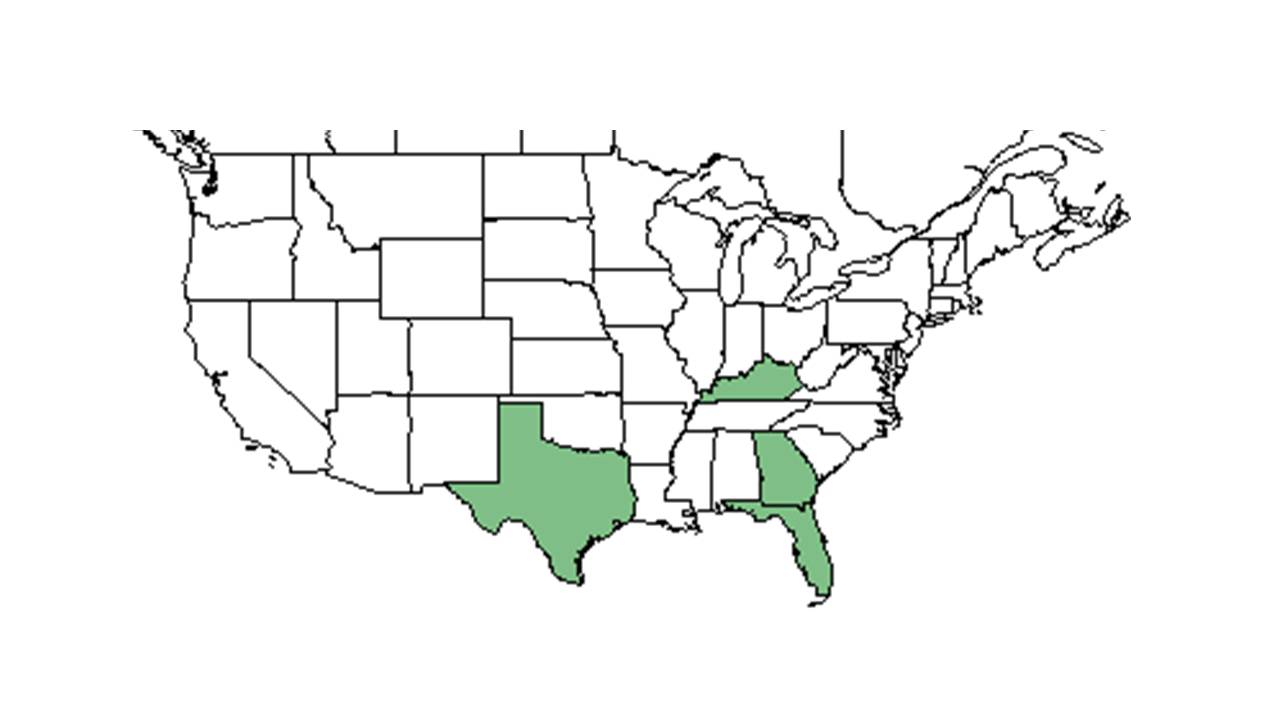

| Natural range of Mimosa quadrivalvis from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Florida sensitive-briar[1]

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Leptoglottis floridana (Chapman) Small ex Britton & Rose; Schrankia microphylla (Dryander) J.F. MacBride var. floridana (Chapman) Isely.[1]

Varieties: Mimosa quadrivalvis Linnaeus var. floridana (Chapman) Barneby.[1]

Description

M. quadrivalvis is an armed sprawling vine with 3-5 pinnae pairs per leaf and leaflets with evident secondary veins.[1]

This species is frequent where it is found and has a sprawling behavior.[2] It is a vining plant that creeps and crawls as well.[2]

Distribution

This species is a southeastern Coastal Plain endemic, ranging from Georgia to Florida.[1]

Ecology

In a study comparing N2 fixation potential in nine legume species occurring in longleaf pine-wiregrass ecosystems, M. quadrivalvis showed clear superiority in growing a large nodule mass to support the high N2 fixation activity.[3] Aboveground N concentration was the greatest for M. quadrivalis species.[3] N2 fixation potential for M. quadrivalvis does not differ between shaded and unshaded environments.[3] The high potential for N2 fixation makes M. quadrivalvis a candidate species for contributing to the N economy in the restoration of longleaf pine ecosystems.[3]

Habitat

This species has been found in open pinewoods, oak-scrub woodlands, prairies, limestone glades, deciduous forests, turkey oak-pinelands, savannas, well drained ridges, ungrazed native grasslands, arroyos, and bare chalk areas.[2] It is commonly found in pine sandhill environments.[4] Occurs in areas that have sandy loam, peat, gravel, and/or clay loam that is dry, loose, or moist.[5][2] Mimosa quadrivalvis is predominately in native groundcover with a statistical affinity in upland pinelands of South Georgia.[6] This species can be found growing in open to semi-shaded areas.[2] M. quadrivalvis responds negatively to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plain communities. This marks it as an indicator species for remnant woodland.[7] It also responds positively to disking in Southern Georgia, especially in double-disked plots where its density was highest.[8] When exposed to soil disturbance by military training in West Georgia, M. quadrivalvis responds negatively by way of absence.[9] It also responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in Southwest Georgia.[10]

Associated species include Pinus palutris, Quercus laevis, Muhlenbergia, Aristida longespica, A. oligantha, Juniperus, Chamaecyparis, Sabal, Magnolia, Acer, Illicium, Salix, Asclepias curtissii, Palafoxia, Paroncyhia, Quercus myrtifolia, Q. geminata, and Serenoa repens.[2]

Phenology

This species has been observed flowering in February as well as April through September and fruiting from April through September.[2]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.[11][12]

Seed bank and germination

Seed coats are hard and viable seed can persist in the seed bank for at least two years.[13]

Fire ecology

This species has been found in areas that are burned.[2]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Mimosa quadrivalvis var. angustata at Archbold Biological Station:[14]

Colletidae: Colletes distinctus

Halictidae: Agapostemon splendens, Augochlorella aurata, Augochloropsis metallica, A. sumptuosa, Lasioglossum miniatulus, L. nymphalis, L. placidensis

Sphecidae: Prionyx thomae

Use by animals

Deyrup observed these bees, Agapostemon splendens, Augochlorella aurata, Augochloropsis sumptuosa, Dialictus miniatulus, D. placidensis, Anthidiellum perplexum on M. quadrivalvis.[15]

Conservation and management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Edwin L. Tyson, J. Dwyer, Kurt Blum, Robert L. Lazor, Loran C. Anderson, J, Craddock Burks, Grady W. Reinert, R.C. Phillips, Gary R. Knight, Norlan C. Henderson, R. Kral, A.F. Clewell, Robert K. Godfrey, William Reese, Paul Redfearn, J.P. Gillespie, Nancy Caswell, Richard S. Mitchell, Patricia Elliot, Gwynn W. Ramsey, D. B. Ward, S. S. Ward, D.S. Correll, Robert J. Lemaire, L.S. Beard, R.O. Vail, W.B. Fox, Edward E. Terrell, S.B. Jones, Sidney McDaniel, V.L. Cory, Brunelle Moon, Cecil R. Slaughter, Robert R. Simons, Angus Gholson, Walter S. Judd, Bob Simons, Tom Morris, William Lindsey, Elmer C. Prichard, L.J. Brass, O. Lakela, John W. Thieret, Gerardo Garcia, Anastacio Bernal, Natalio Castillo, Guillermo Perez, Nick Lopez, W. L. McCart, D. S. Correll, I. M. Johnston, Duane Isely, F. L. Lewton, H. R. Reed, L. S. Beard, and R O Vail. States and Counties: Florida: Calhoun, Citrus, Duval, Franklin, Gadsden, Highlands, Indian River, Jackson, Lake, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Marion, Nassau, Osceola, Pinellas, Polk, Suwannee, Taylor, Wakulla, Walton, and Volusia. Georgia: Seminole, and Thomas. Arkansas: Clark and Washington. North Carolina: Robeson and Rockingham. Alabama: Pickens and Sumter. Louisiana: Acadia. Texas: Andrews,Aransas, Callahan, Comal, Dallas, Denton, Dimmit, Ft. McKanepp, Haskell, Leon, Sutton, Taylor, Van Zandt, and Zapata. Kansas: Franklin. Missouri: Bates and Greene. Countries: Panama.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Cathey, S. E., L. R. Boring, et al. (2010). "Assessment of N2 fixation capability of native legumes from the longleaf pine-wiregrass ecosystem." Environmental and Experimental Botany 67: 444-450.

- ↑ Downer, M. R. (2012). Plant species richness and species area relationships in a Florida sandhill community. Integrative Biology. Ann Arbor, MI, University of South Florida. M.S.: 52.

- ↑ Miller, J. H., R. S. Boyd, et al. (1999). "Floristic diversity, stand structure, and composition 11 years after herbicide site preparation." Canadian Journal of Forest Research 29: 1073-1083.

- ↑ Ostertag, T.E., and K.M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Pages 109–120 in R.E. Masters and K.E.M. Galley (eds.). Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Buckner, J.L. and J.L. Landers. (1979). Fire and Disking Effects on Herbaceous Food Plants and Seed Supplies. The Journal of Wildlife Management 43(3):807-811.

- ↑ Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Maza-Villalobos, S., C. Lemus-Herrera, et al. (2011). "Successional trends in soil seed banks of abandoned pastures of a Neotropical dry region." Journal of Tropical Ecology 27: 35-49.

- ↑ Coffey, K. L. and L. K. Kirkman (2006). "Seed germination strategies of species with restoration potential in a fire-maintained pine savanna." Natural Areas Journal 26: 289-299.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Deyrup, M. J. E., and Beth Norden (2002). "The diversity and floral hosts of bees at the Archbold Biological Station, Florida (Hymenoptera: Apoidea)." Insecta mundi 16(1-3).