Liquidambar styraciflua

Common name: Sweetgum[1], Red gum[2]

| Liquidambar styraciflua | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Southeastern Flora Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Hamamelidales |

| Family: | Hamamelidaceae |

| Genus: | Liquidambar |

| Species: | L. styraciflua |

| Binomial name | |

| Liquidambar styraciflua L. | |

| |

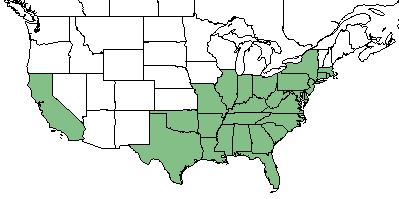

| Natural range of Liquidambar styraciflua from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: none.[3]

Varieties: none.[3]

Description

L. styraciflua is a perennial tree of the Hamamelidaceae family native to North America.[1]

Distribution

L. styraciflua ranges from Connecticut, west to southern Ohio, Illinois, and Oklahoma, and south to southern Florida, Texas, and Guatemala.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

L. styraciflua is found in swamp forests, floodplains, moist forests, depressional wetlands, old fields, and disturbed areas.[2] Specimens have been collected from hardwood swamp, lowland woodland, wet hammock, lake edges, pine woods, mixed woodland, wet slash pine, sand bluffs, and the edge of mesic woodlands.[4]

L. styraciflua responds positively to soil disturbance by heavy silviculture in North Carolina.[5] When exposed to soil disturbance by military training in West Georgia, L. styraciflua responds negatively by way of absence.[6] It exhibits no response to soil disturbance by improvement logging in Mississippi.[7] L. styraciflua responds negatively to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[8] It also responds negatively to soil disturbance by roller chopping and disturbance by a KG blade in East Texas Loblolly Pine-Hardwood Forests.[9]

Liquidambar styraciflua is frequent and abundant in the North Florida Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[10]

Phenology

L. styraciflua flowers from April through May.[11]

Fire ecology

L. styraciflua is quite fire resistant.[12]

Use by animals

L. styraciflua has medium palatability for browsing animals[1], and the bark is a favorite food of beavers. Additionally, the sap used to be gathered as chewing gum.[2]

Conservation and Management

L. styraciflua is listed as a species of special concern by the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection.[1]

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 USDA Plant Database https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=LIST2

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Cecil Slaughter, R.K. Godfrey, Kathy Craddock Burks, David A. Breil, Kurt Blum, Andre F. Clewell, Patricia Elliot, Gary Knight, A. Gholson Jr., Richard P. Wunderlin, Bruce Hansen, Karen MacClendon, Paul L. Redfearn, M.P. Burbank, Sherman, Shamblee, John W. Thieret, G.S. Ramseur, A.E. Hammond, Windler, M. Burch, Clarke Hudson, D.S. Correll, Raymond Jones, R. E. Wicker, Ed Keppner, Lisa Keppner, Richard Gaskalla, Ana Ochoa, Marc Minno. States and counties: Florida (Marion, Leon, Jefferson, Liberty, Walton, Dixie, Jackson, Santa Rosa, Levy, Hernando, Madison, Gadsden, Hillsborough, Wakulla, Calhoun, Osceola, Baker, St. Johns, Washington, Holmes) Georgia (THomasGrady, De kalb, Clarke) Arkansas (Stone, Searcy, Marion) North Carolina (Moore, Alamance) West Virginia (Cabell) Louisiana (Washington, Bienville, Evangeline, Tangipahoa, Lafayette, Lincoln) Tennessee (Coffee) Maryland (St. Marys) Mississippi (Forrest)

- ↑ Cohen, S., R. Braham, and F. Sanchez. (2004). Seed Bank Viability in Disturbed Longleaf Pine Sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.

- ↑ Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ McComb, W.C. and R.E. Noble. (1982). Response of Understory Vegetation to Improvement Cutting and Physiographic Site in Two Mid-South Forest Stands. Southern Appalachian Botanical Society 47(1):60-77.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Stransky, J.J., J.C. Huntley, and Wanda J. Risner. (1986). Net Community Production Dynamics in the Herb-Shrub Stratum of a Loblolly Pine-Hardwood Forest: Effects of CLearcutting and Site Preparation. Gen. Tech. Rep. SO-61. New Orleans, LA: U.S. Dept of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Forest Experiment Station. 11 p.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 24 MAY 2018

- ↑ Brockway, D. G., et al. (2005). Restoration of longleaf pine ecosystems. F. S. United States Department of Agriculture, Southern Research Station.