Lepidium virginicum

| Lepidium virginicum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Capparales |

| Family: | Brassicaceae ⁄ Cruciferae |

| Genus: | virginicum |

| Species: | L. virginicum |

| Binomial name | |

| Lepidium virginicum L. | |

| |

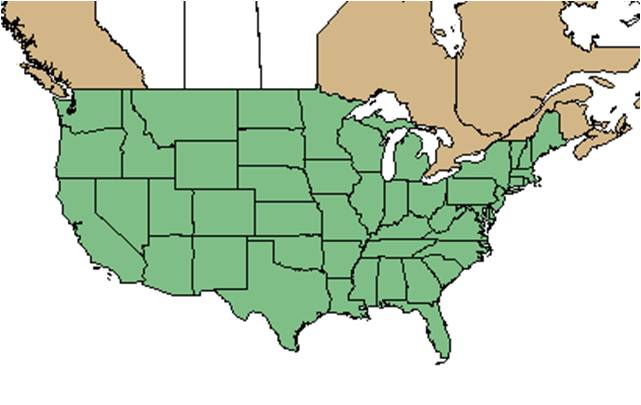

| Natural range of Lepidium virginicum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Virginia pepperweed

Contents

Taxonomic notes

It is similiar to Lepidium campestre in both appearance and growth habitat; however,the lobed rosette leaves and the bottle brush appearance of mature L. virginicum can help distinguish the two species [1].

Description

A description of Lepidium virginicum is provided in The Flora of North America.

L. virginicum is a prolific weed that can either be an annual or biennial species, depending on environmental conditions [2]. Initially, it appears as a low growing rosette with pinnatifid leaves, later, the stems emerge upward, occasionally branching, often becoming bushy. Flowers can be found blooming at the top of the raceme, at the bottom, flattened seedpods take the place of flowers, often said to resemble a bottle-brush[3][1]. The flowers are small and white, with 4 petals and 2 stamens[2].

Distribution

This species can be found throughout North America, except Prairie Provinces and parts of the far north [2].

Ecology

Habitat

L. virginicum is usually found in disturbed areas such as roadsides, vacant lots, sandy fallow fields, and lawns. It has also be found in natural communities such as river floodplains, marshy salt flats bordering mangrove swamps, and sandy flats and shores of shallow lakes (FSU Herbarium). This species has been found growing in highly disturbed areas such as the Copper Basin, which has long been subjected to sulfur dioxide pollution and it has been observed to have a ecotypic adaptation resulting from natural selection in this area (Murdy 1979).

Soils include loamy sand and sandy loam. Associated species include cyperus and mangroves (FSU Herbarium).

Phenology

Initially L. virginicum appears as a low growing rosette with pinnatifid leaves, with a stem emerging later, branching occasionally, causing the plant to be bushy [3]. The tiny white flowers have 4 petals and 2 stamens and are found at the top of the raceme, with seeds appearing on the lower end of the raceme, replacing the flowers. It can be observed flowering and fruiting February through November (FSU Herbarium).

Seed dispersal

The individual seedpods may be carried a short distance by the wind or an entire raceme of mature seedpods will become detached from the mother plants and drift away in the wind [3].

Seed bank and germination

In a study conducted by Toole and Cathey (1961) it shows that when treated with gibberellic acid, seeds can germinate in total darkness and higher temperatures. Toole and Toole (1955) found that Coumarin promotes germination to at a certain level (1.1*10^-4) and past this level, causes inhibition.

Fire ecology

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Lepidium virginicum at Archbold Biological Station (Deyrup 2015):

Colletidae: Colletes mandibularis

Halictidae: Augochlorella gratiosa

Megachilidae: Heriades leavitti

Sphecidae: Ectemnius rufipes ais, Oxybelus laetus fulvipes, Tachysphex similis

Vespidae: Stenodynerus fundatiformis

Use by animals

Commonly used as a food source for the larvae of Pieris butterflies and noctuid moths, aphids, beetles, and grasshoppers. There is an induced response to herbivory such as increasing the number of trichomes per leaf. Pieris rapae caterpillars are not affected by the induced response of herbivory to this species (Agrawal 2000).

Diseases and parasites

Conservation and Management

L. virginicum can often be thought of as a noxious weed in some crops. Alida et al. (1998) found populations of L. virginicum that are resistant to paraquat applications in southern Ontario.

Cultivation and restoration

The seeds are often eaten for their peppery taste [2]. There are health promoting properties of L. virginicum that have been used in traditional Mexican medicine to treat diarrhea and dysentery (Osuna et al. 2006).

Photo Gallery

References and notes

Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: October 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, D.J. Banks, D.E. Breedlove, D. Burch, Andre F. Clewell, K. Craddock Burks, Suellen Folensbee, R.K. Godfrey, Gary R. Knight, Robert M. Laughlin, O. Lakela, Robert J. Lemaire, S.W. Leonard, Marc Minno, Richard Mitchell, Jackie Patman, Elmer C. Prichard, Gwynn W. Ramsey, Peter H. Raven, Cecil R. Slaughter, Victoria I. Sullivan, L.B. Trott, Edwin L. Tyson, Bruce Walton, D.B. Ward, Jean Wooten. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Brevard, Collier, Dixie, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Hamilton, Hernando, Hillsborough, Holmes, Indian River, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Marion, Okaloosa, Orange, Polk, St. Johns, Taylor, Union, Volusia, Wakulla, Walton. Countries: Mexico, Panama. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.