Houstonia procumbens

| Houstonia procumbens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo was taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Rubiales |

| Family: | Rubiaceae |

| Genus: | Houstonia |

| Species: | H. procumbens |

| Binomial name | |

| Houstonia procumbens (Walter ex J.F. Gmel.) Standl. | |

| |

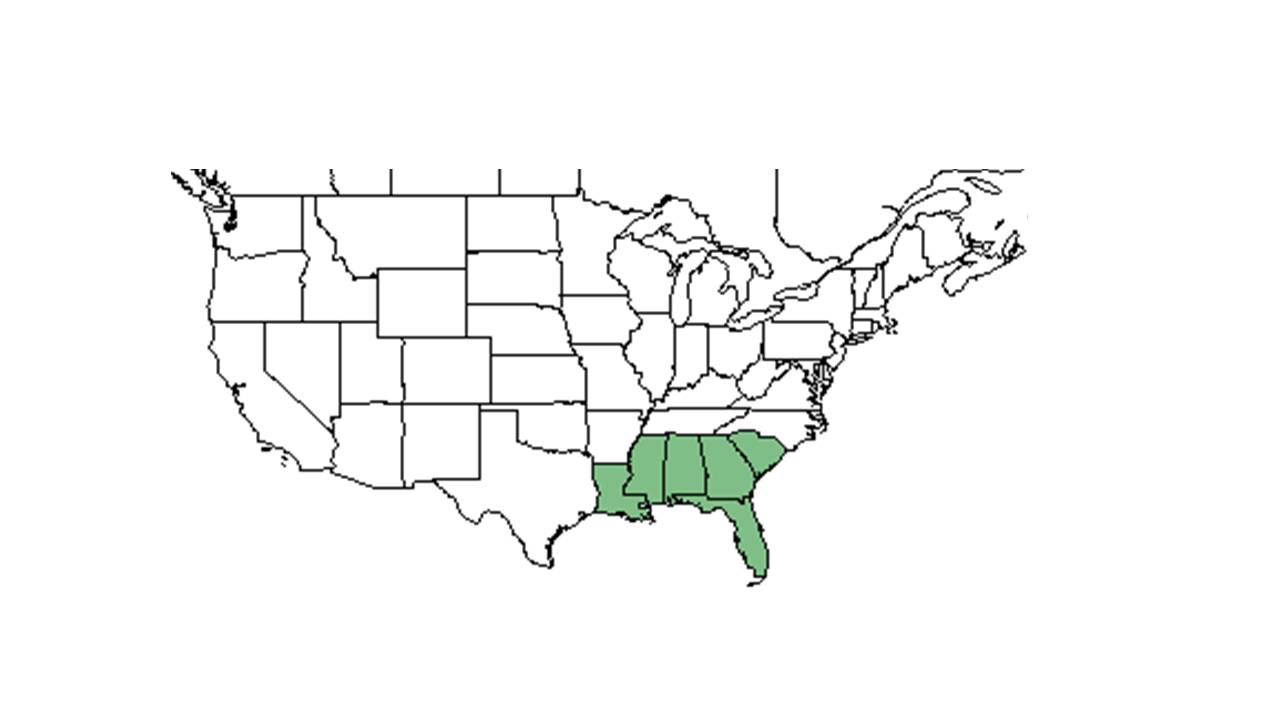

| Natural range of Houstonia procumbens from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: roundleaf bluet; creeping bluet; fairy-footprints; innocence

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Hedyotis procumbens (Walter ex J.F. Gmelin) Fosberg; Houstonia rotundifolia Michaux[1]

Varieties: Houstonia procumbens var. hirsuta (W.H. Lewis) D.B. Ward; H. procumbens var. procumbens[1]

The great variation in this plant's pubescence merits further study for possible varieties within the species.[2]

Description

Houstonia procumbens is a perennial herbaceous species with a procumbent, spreading growth habit and small white flowers.[3]

"Erect or creeping annuals or perennials. Leaves opposite, the bases connected by small stipules. Flowers in cymes or appearing solitary; sepals 4, lanceolate or subulate; corolla salverform or funnelform, lobes usually shorter than the tube; stamens 4, included. Capsule 2-locular, slightly flattened, the lower ½ enclosed by the calyx tube, the apex loculicidal."[4]

"Prostrate or weakly decumbent, creeping perennial, the solitary pedicels erect, 1-4 cm tall. Leaves widely ovate to suborbicular, 7-10 mm long, 4-10 mm wide, margins ciliolate. Corolla white, the tube 5-7 mm long, glabrous within, lobes 4-6 mm long. Capsule 3-4 mm broad." [4]

Distribution

It is distributed in the southeastern coastal plain, from southeastern South Carolina south to southern Florida and west to southeastern Louisiana.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Generally, H. procumbens can be found on wet to moist sandy pinelands as well as beach dunes.[1] As well, it grows in mostly moist open areas and pinelands or disturbed sites.[5] It occurs in moist to dry sandy or loamy soils, or in loose sand. It can be found in light conditions from partial shade to full sun. H. procumbens was found to decrease in occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in southwest Georgia. It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished native savanna communities that were disturbed by agricultural practices.[6] Native habitat it can be found in includes longleaf pine-scrub oak-wiregrass sand ridges, mixed hardwood woodlands, open slash pine stands, sand dunes, turkey oak scrub, and on stream banks. However, it can also occur in disturbed habitat such as roadsides, parking areas, cutover pinewoods, mowed lawns, bulldozed slash pine savannas, open pastures, and along trails.[3]

Associated species include Pinus palustris, Quercus, Aristida stricta, Pinus elliottii, Quercus virginiana, Phlox floridana, Stillingia sylvatica, Asimina longifolia var. spathulata, Lactuca graminifolia, Stylosanthes biflora, Erigeron strigosa, Baptisia lanceolata, Hedyotis crassifolia, Pterocaulon undulatum, Asclepias humistrata, and Quercus hemisphaerica.[3]

Houstonia procumbens is frequent and abundant in the North Florida Longleaf Woodlands and Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[7]

Phenology

This species generally flowers from October until April. Since it flowers in the winter, it can easily be overlooked by botanists who are more likely to be in the field around other times.[1] It has been observed flowering in January through May, July, August, and October with peak inflorescence in February. Fruiting has been observed in February through May, October, and November.[3][8] From the upper peninsula of Florida southward its flowering tends to be limited to the winter months.[9]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity. [10] Edwin Bridges and Alex Griffel observed in a sandhill woodland scrubby flatwoods in Polk County, Florida that, following flowering, as the fruit develops, the pedicels of the fruit recurve, and the fruit becomes buried in the sand below the prostrate leafy stems. When flowering is done, from above it looks like the plants are vegetative only, but if you pull them up and turn them over you can see abundant fruit.[11]

Seed bank and germination

For more successful germination, seeds of H. procumbens should be treated with moist stratification.[5] In multiple longleaf pine communities, it was found both in the standing vegetation and in the seedbank.[12][13] Another study by Navarra found that seeds of this species were in higher frequency in the seed bank of fire disturbed areas rather than unburned areas.[14]

Fire ecology

This species has been found in habitat that is often maintained by occasional fire,[3] and populations of Houstonia procumbens have been known to persist through repeated annual burning.[15] It benefits most from summer burn regiments and then lesser spring burn regiments rather than winter burn regiments.[16] As well, fire disturbance has been shown to increase the amount of seeds in the seed bank rather than leaving an area unburned.[14] With this, seedling emergence was seen to increase with fire disturbance in comparison to a site that was unburned.[13]

Pollination

Houstonia procumbens is a nectar source in late winter and early Spring, visited by butterflies including the zebra swallowtail (Eurytides marcellus).[17]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Ward, D. B. (2004). "New combinations in the Florida flora II." Novon 14(3): 365-371.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Harry E. Ahles, Loran C. Anderson, George R. Cooley, Delzie Demaree, Patricia Elliott, Suellen Folensbee, J. P. Gillespie, Robert K. Godfrey, Gary R. Knight, R. Komarek, R. Kral, Sidney McDaniel, R. S. Mitchell, Joseph Monachino, R. A. Norris, Kevin Oakes, Elmer C. Prichard, Gwynn W. Ramsey, W. D. Reese, Paul O. Schallert, John W. Thieret, L. B. Trott, and Jean W. Wooten. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Brevard, Citrus, Franklin, Gadsden, Jackson, Jefferson, Lafayette, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Polk, Sarasota, Seminole, Suwannee, Volusia, Wakulla, Walton, and Washington. Georgia: Grady and Thomas. Louisiana: Washington. South Carolina: Colleton.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 981-3. Print.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 22, 2019

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 DEC 2016

- ↑ Amye C. Travis post to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Group on Facebook, January 4, 2017.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Edwin Bridges post to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Group on Facebook, February 23, 2017.

- ↑ Andreu, M. G., et al. 2009. Can managers bank on seed banks when restoring Pinus taeda L. plantations in southwest Georgia? Restoration Ecology 17:586-596.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Parks, G. R. (2007). Longleaf pine sandhill seed banks and seedling emergence in relation to time since fire, University of Florida. Master of Science: 84.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ Post by "Brenda's Butterfly Habitat" to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Post on Facebeook, February 18, 2015.