Elephantopus elatus

| Elephantopus elatus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Elephantopus |

| Species: | E. elatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Elephantopus elatus Bertol. | |

| |

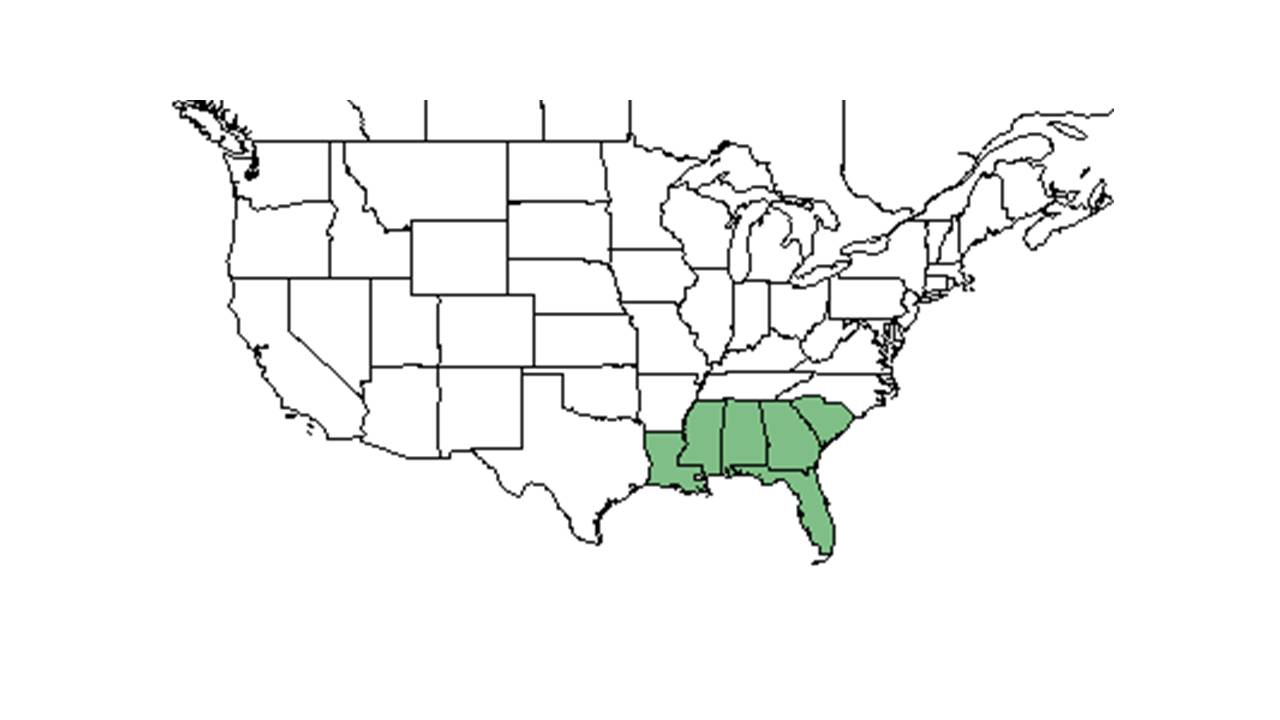

| Natural range of Elephantopus elatus from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: tall elephantsfoot; Southern elephant's-foot

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Description

A description of Elephantopus elatus is provided in The Flora of North America. It is usually a single plant, up to 1m tall, stems are rigid and brittle, with a pappus (modified calyx), flowers are lavender to white, and achenes are 3.5-4m. [1]

Distribution

Distributed from South Carolina, south to Florida and west to Louisiana.[2] More specifically in this range, it is found from eastern South Carolina to southern Florida as well as southeastern Louisiana.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

Generally, E. elatus can be found in pine sandhills or flatwoods.[3] It is found in well drained, open pinelands, longleaf pine-wiregrass sand ridges, slash pine flatwoods, longleaf pine savannas, pine-oak woodlands, pine-palmettos woodlands, oak hammock woodland, edges of river banks, sandhills, and edges of upland mixed forest with exposed limestone.[1] In the dry prairies of South Florida, it is limited to the "Dry Mesic" community type, which is the highest and driest within that landscape, but which occurs on poorly drained to somewhat poorly-drained Spodosols, mostly arenic or aeric haplaquods (Immokalee and Myakka series), with a perched wet-season water table.[4] Is also found in human disturbed areas that have been logged or clear cut (like flatwoods), along the roadsides, and in roadside depressions. Requires high levels of light in open areas. Is associated with loam soil, sandy loam soil, limestone, and clay soil types. [1] It prefers dry soil to wetter soil.[5] It is found in dry flatwoods and sandhill communities. [5] E. elatus responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in Southwest Georgia.[6]

Associated species include Cocculus carolinus, Pinus palustris, Pinus elliottii, Aristida sp., Quercus laevis, Quercus incana, and other Quercus sp.[1]

Elephantopus elatus is frequent and abundant in the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[7]

Phenology

E. elatus generally flowers from August until November.[3] This species has been observed to flower from July to November.[1][8] One study found flower duration to be longer in burned plots.[9]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind. [10]

Seed bank and germination

It was found viable in the seed bank of a pine flatwoods community in Florida in areas fire excluded for up to 29 years.[11]

Fire ecology

It responded positively to late winter annual and biennial burns.[5] Is abundant in area where there was a winter burn, observed in annually burned savannas, Longleaf pinelands, and in pine-oak woodlands. [1] Flower duration has also been shown to increase with fire regiments. The most notable difference in the vigor of the flowering response occurred 1 month after the burns and in the fall flowering censuses.[9]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Elephantopus elatus at Archbold Biological Station. [12]

Halictidae: Augochlora pura, Augochlorella aurata, Augochloropsis metallica

Leucospididae: Leucospis slossonae

Megachilidae: Anthidiellum perplexum, Megachile albitarsis, M. brevis pseudobrevis, M. xylocopoides

Sphecidae: Isodontia exornata

Vespidae: Pachodynerus erynnis, Stenodynerus fundatiformis

Use by animals

These bees, Azcgochlora pura, Augochlorella aurata, Azegochloropsis metallica, Anthidiellum perplexurn, Megachile albitarsis, M. brevis pseudobrevis, and M. xylocopoides, were found on E. elatus.[13] This species is eaten by adult and juvenile gopher tortoises (Gopherus polyphemus).[14]

Conservation and management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: R.K. Godfrey, R. D. Houk, R. L. Lazor, John Lazor, K. E. Blum, J. Wooten, James D. Ray, Jr., O. Lakela, A. F. Clewell, J. P. Gillespie, R. E. Perdue, Cecil R Slaughter, Loran C. Anderson, Brenda Herring, Don Herring, Gary R. Knight, Robert Kral, D. B. Ward, T. Myint, Richard S. Mitchell, E. L. Tyson, S. S. Ward, R. R. Smith, A. A. Will, Paul O. Schallert, L. Baltzell, Paul L. Redfearn, Jr., R. Komarek, MacClendons, G. Wilder, and Billie Bailey. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Citrus, Clay, Columbia, Dixie, Duval, Escambia, Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Hernando, Highlands, Hillsborough, Indian River, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Marion, Okaloosa, Okeechobee, Orange, Osceola, Pasco, Polk, Putnam, Sarasota, Seminole, St Johns, Taylor, Volusia, Wakulla, and Walton. Georgia: Grady and Thomas.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 6 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ Orzell, S.L. and E.L. Bridges. 2006. Species composition and environmental characteristics of Florida dry prairies from the Kissimmee River region of south-central Florida. Pages 100-135 in Land of fire and water: The Florida dry prairie ecosystem. Proceedings of the Florida Dry Prairie Conference, R. F. Noss (ed).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, et al. (2003). "Fire frequency effects on longleaf pine (Pinus palustris, P.Miller) vegetation in South Carolina and northeast Florida, USA." Natural Areas Journal 23: 22-37.

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 6 MAY 2019

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Heuberger, K. A. and F. E. Putz (2003). "Fire in the suburbs: ecological impacts of prescribed fire in small remnants of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) sandhill." Restoration Ecology 11: 72-81.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Maliakal, S.K., E.S. Menges and J.S. Denslow. 2000. Community composition and regeneration of Lake Wales Ridge wiregrass flatwoods in retlation to time-since-fire. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 127:125-138.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Deyrup, M. J. E., and Beth Norden (2002). "The diversity and floral hosts of bees at the Archbold Biological Station, Florida (Hymenoptera: Apoidea)." Insecta mundi 16(1-3).

- ↑ Mushinsky, H. R., Terri A. Stilson and Earl D. McCoy (2003). "Diet and Dietary Preference of the Juvenile Gopher Tortoise " Herpetologists' League 59(4): 475-486.