Diodella teres

| Diodella teres | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Rubiales |

| Family: | Rubiaceae |

| Genus: | Diodella |

| Species: | D. teres |

| Binomial name | |

| Diodella teres Walter | |

| |

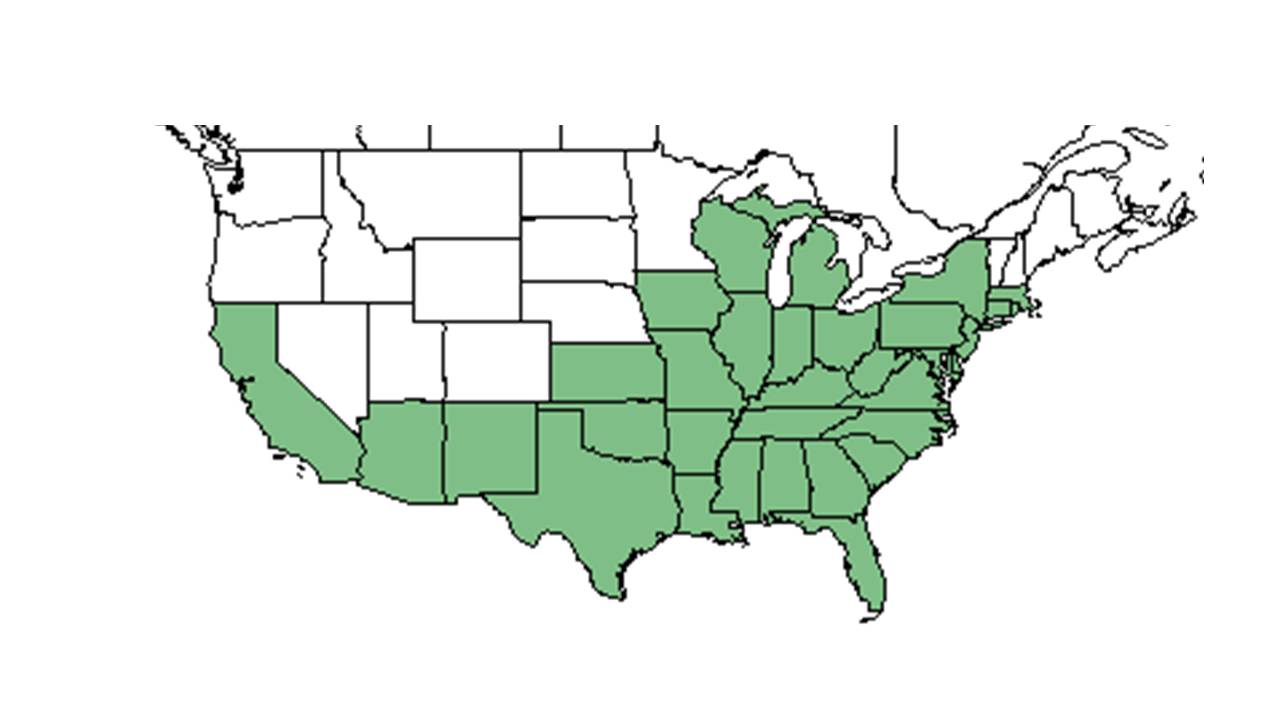

| Natural range of Diodella teres from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Poorjoe

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Diodia teres Walter; Diodia teres var. hirsutior Fernald & Griscom; Diodia teres var. hystricina Fernald & Griscom; Diodia teres var. oblongifolia Fernald; Diodia teres var. teres

Description

Generally, for Diodia genus (this description is from Radford 1964. Diodella was not an accepted name at the time) they are "annual or perennial herbs. Leaves sessile, opposite pubescent or glabrate, margins hyaline, setose-serrate; stipules linear or fimbriate, ½ as long, or longer than, the fruit. Flowers 4-merous, axillary, usually solitary, sessile; calyx lobes equal or unequal; corolla salverform. Fruit leathery, surmounted by the persistent calyx lobes, splitting into 2, indehiscent, 1-seeded segments." [1]

Specifically, for D. teres, they are "erect or spreading, usually pubescent perennial from a woody root crown, the stems branched, 1-6 dm or more long. Leaves elliptic-lanceolate to oblanceolate, mostly 2-7 cm long, 4-21 mm wide. Calyx lobes 2, linear-lanceolate, 4-6 mm long, pubescent; corolla white, tube 4-5 mm long, glabrous; stigma 2-lobed. Fruit hispid, obpyriform, 2.5-4 mm long, with a single longitudinal furrow. Fruit splitting into 2, indehiscent, 1-seeded segments." [1]

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

D. teres occurs in semi-shaded to open areas and well-drained sandy soil.[2] It can be found in longleaf pine savannas,[3] turkey oak sand ridges, mixed hardwood forests, exposed coastal dunes, coastal hammocks, and scrub hills.[2]

This species decreased significantly in response to clearcutting and thinning. This is evidence that Diodella teres prefers relatively undisturbed areas as to disturbed areas.[4] However, it still occurs in some disturbed habitats, including roadsides and railroad yards.[2]

In the Piedmont, it has been observed to occur in areas of washing with most or all of the A horizon destroyed.[5]

Associated species include Toxicodendron, Rubus cuneifolius, Pteridium aquilinum, Elephantopus tomentosus, Triplasis purpurea, Crotalaria, Desmodium, D. virginiana, Serenoa repens, live oak, pine.[2]

Phenology

Flowering has been observed in June through October, and fruiting has been observed in June through November.[2]

Seed dispersal

This species disperses by gravity. [6]

Fire ecology

This species has been found frequently burned areas, including annually burned pinelands.[2] It appears to benefit especially from high fire frequency (in the Osceola study plots).[7]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Diodia teres at Archbold Biological Station: [8]

Halictidae: Augochloropsis sumptuosa

Sphecidae: Prionyx thomae

Use by animals

It is an important food to bobwhites in the summer months.[9] It is also a principal food for the morning dove in north-central Florida in October and December.[10]

The bee Augochloropsis suinptzosa was found on D. teres.[11]

Conservation and management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 979. Print.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Tom Barnes, A. F. Clewell, D. L. Fichtner, J. P. Gillespie, R. K. Godfrey, Bruce Hansen, R. Kral, Robert L. Lazor, Cecil R. Slaughter, Gwynn W. Ramsey, H. Larry Stripling, Brenda Herring, Wendy Zomlefer, Mabel Kral, D. W. Mather, F. C. Craighead, R. A. Norris, R. Komarek, Edwin L. Tyson, and JoAnn Hansen. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Bay, Citrus, Dade, Duval, Escambia, Franklin, Highland, Holmes, Jefferson, Lake, Leon, Liberty, Madison, Marion, Okaloosa, Orange, Polk, Santa Rosa, St. Johns, Taylor, Wakulla, and Walton. Georgia: Grady and Thomas. Other countries: Panama.

- ↑ Heuberger, K. A. and F. E. Putz (2003). "Fire in the suburbs: ecological impacts of prescribed fire in small remnants of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) sandhill." Restoration Ecology 11: 72-81.

- ↑ Brockway, D. G. and C. E. Lewis (2003). "Influence of deer, cattle grazing and timber harvest on plant species diversity in a longleaf pine bluestem ecosystem." Forest Ecology and Management 175: 49-69.

- ↑ McQuilkin, W. E. (1940). "The Natural Establishment of Pine in Abandoned Fields in the Piedmont Plateau Region." Ecology 21(2): 135-147.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, et al. (2003). "Fire frequency effects on longleaf pine (Pinus palustris, P.Miller) vegetation in South Carolina and northeast Florida, USA." Natural Areas Journal 23: 22-37.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Jones, J. D. J. and M. J. Chamberlain (2004). "Efficacy of herbicides and fire to improve vegetative conditions for northern bobwhites in mature pine forests." Wildlife Society Bulletin 32: 1077-1084.

- ↑ Beckwith, S. L. (1959). "Mourning Dove Foods in Florida during October and December." The Journal of Wildlife Management 23(3): 351-354.

- ↑ Deyrup, M. J. E., and Beth Norden (2002). "The diversity and floral hosts of bees at the Archbold Biological Station, Florida (Hymenoptera: Apoidea)." Insecta mundi 16(1-3).