Cuscuta compacta

| Cuscuta compacta | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Solanales |

| Family: | Cuscutaceae |

| Genus: | Cuscuta |

| Species: | C. compacta |

| Binomial name | |

| Cuscuta compacta Juss | |

| |

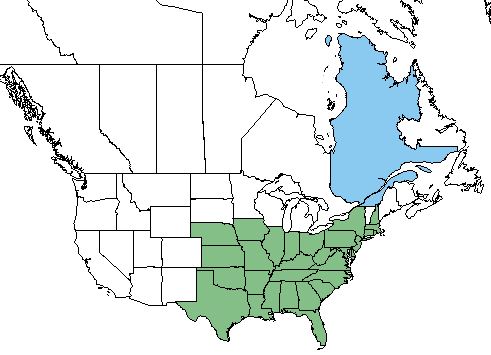

| Natural range of Cuscuta compacta from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common Name: compact dodder[1][2]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: C. compacta var. compacta; C. compacta var. efimbriata Yuncker [1][2]

Varieties: none

Description

C. compacta is a parasitic dioecious perennial that grows as a forb/herb or a vine.[2] Stems are more than 2 mm in diameter, yellow-green, and form rope-like masses. Although this species is typically a light green color, there is considerable variation within the species. Its inflorescence is a glomerule of 3-5 tubular flowers 5 mm long and 2 mm wide. Seeds are 2-2.6 mm long, brown when fresh, scurfy, globose, ovate to angled or flattened, and oblong.[3][4]

Distribution

C. compacta occurs from Nebraska, south to Texas, eastward to central peninsular Florida, and northward to Illinois, New York, and New Hampshire.[1][2] It has also been introduced in Quebec Canada.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

C. compacta is found on herbaceous and woody hosts in bottomland forests, stream banks, marshes, swamps, pine savannahs, wet fields, and other wet habitats.[1][3] This species has been reported parasitizing a wide range of species[3], including Vaccinium ashei and Vaccinium corymbosum in North Carolina[5] and Citrus sinensis in Florida.[6] In Virginia, C. compacta is the only dodder to grow on Alnus serrulata, and has not been recorded parasitizing any monocots. Other frequent hosts in Virginia include species of Acer, Liquidambar, Rubus, Rhus, and Aralia.[3]

Phenology

In the southern and mid-Atlantic United States, C. compacta has been observed to flower from late July through November.[1][7] Flowering in Virginia occurs from August 15th to September 28th.[3]

Seed bank and germination

In Virginia, C. compacta has a very high percentage of seed set. Germination occurs best at temperatures of 22-23 °C.[3]

Pollination

While other species of Cuscuta are well adapted for insect pollination, C. compacta is well developed for autogamy.[3]

Use by animals

Pawnee Indians would use C. compacta to dye materials, such as feathers, orange. Maidens of the Pawnee would also use the parasite for divination to determine if their suitors sincerely loved them. A Mexican Indian has reported that rattlesnakes would take this plant into their dens for food.[8]

Diseases and parasites

C. compacta is reported to transmit the psorosis virus to 5% of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) tested.[6]

Conservation and Management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley AS (2015) Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 USDA NRCS (2016) The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 24 January 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Musselman LJ (1986) The genus Cuscuta in Virginia. Castanea 51(3):188-196.

- ↑ Austin DF (1980) Studies of the Florida Convolvulaceae - III. Cuscuta. Florida Scientist 43(4):294-302.

- ↑ Monaco TJ, Mainland CM (1981) Cuscuta compacta on blueberries in North Carolina. Haustorium, Parasitic Plants Newsletter 7:1.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Price WC (1965) Transmission of psorosis virus by dodder. International organization of citrus virologists conference proceedings (1957-2010) 3(3):162-166.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 24 JAN 2018

- ↑ Gilmore MR (1919) Uses of plants by the indians of the Missouri river region. Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Annual Report 33.