Conyza canadensis

| Conyza canadensis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Conyza |

| Species: | C. canadensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronquist | |

| |

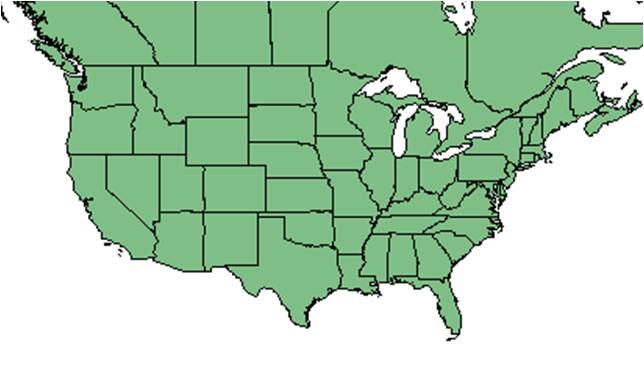

| Natural range of Conyza canadensis from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Canadian Horseweed; Common Horseweed

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Conyza parva Cronquist; Erigeron canadensis Linnaeus; Erigeron canadensis Linnaeus var. canadensis; Erigeron canadensis Linnaeus var. pusillus (Nuttall) Boivin; Erigeron pusillus Nuttall; Leptilon canadense (Linnaeus) Britton; Leptilon pusillum (Nuttall) Britton.[1]

Varieties: Conyza canadensis (Linnaeus) Cronquist var. canadensis; Conyza canadensis (Linnaeus) Cronquist var. pusilla (Nuttall) Cronquist.[1]

Description

A description of Conyza canadensis is provided in The Flora of North America.

Distribution

Generally, C. canadensis is native across North America, from the continental United States to most of Canada, and on Navassa Island, Puerto Rico, St. Pierre and Miquelon, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The species has been introduced to Alaska, Hawaii, and the Pacific Basin.[2] It was introduced to Europe in the 17th century.[3] Conyza canadensis var. canadensis is widespread, distributed from south Canada throughout the United States and into tropical America, whereas C. canadensis var. pusilla is distributed from southeast Massachusetts and Connecticut to south Indiana, down to Florida and Texas as well as into tropical America.[4]

Ecology

Habitat

Conyza canadensis can be found in a range of habitats from old fields to dunes, as well as gardens and disturbed areas.[4] This plant is a common pest of agricultural fields, and can grow on a range of acidic to neutral soils (pH 4.8 to 7.2).[3] Additionally, C. canadensis was found in the seed bank of scrub, longleaf pine, and ecotone habitats in the western panhandle region of Florida.[5] The species has also been observed in sandy pine plantations, pine flatwoods, scrub, open sand ridges, coastal dunes, and ridges.[6] C. canadensis is a common indicator for disturbance, since it commonly colonizes disturbed areas that it was either absent or sparse from before the disturbance.[7] Pine thinning increases the abundance of the species.[8]

Associated species exclude Ambrosia sp., Erechtites, Andropogon sp., Baccharis sp., Setaria sp., Cenchrus sp., Serenoa sp., Uniola sp., Liatris sp., Panicum sp., Eupatorium sp., Cassia sp., Schizachyrium sp., Muhlenbergia capillaris, Leptoloma cognatum, Quercus laevis, and Pinus palustris.[6]

Phenology

Flowering season of C. canadensis var. canadensis is from July to November while flowering season of C. canadensis var. pusilla is from July to December as well as occasionally May to December.[4] C. canadensis has been observed to flower in June.[9] Flowering in mid to late summer can be due to fall seed germination.[3] It has been observed to fruit in July, September, and October.[6]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind. [10] It produces a large amount of seeds that can easily colonize disturbed soils through wind.[3] One study found the seeds to travel at least 500 meters from the source populations.[11]

Seed bank and germination

C. canadensis germinates from seed at any time of the year with sufficient warmth and moisture. If it germinates in the fall, it overwinters as a rosette and bolts in the spring to flower in the summer, whereas if it germinates in the spring, the individual spends less time as a rosette before it bolts to flower.[3] One study found C. canadensis to be present in the seed bank of disturbed sites as well as non-disturbed sites, but it was more prevalent in the seed bank of disturbed sites.[12] It was also found to persist in the seed bank after a fire.[13] With this, another study found seeds of C. canadensis to persist in the seed bank up until 6 years after a fire disturbance.[14] During old field succession, it has been found to persist in the seed bank with high frequency, but to peak within the first five years of succession.[15] One study found C. canadensis to germinate the most from the seed bank on disturbed dunes, followed by low areas and back slopes.[16] As well, germination in one study was stimulated to increase by scarification.[17]

Fire ecology

It has been observed to grow in firelanes that are utilized for prescribed fires.[6] C. canadensis has also been shown to increase in frequency in response to increasing fire frequency regiments.[18] This could be due to seeds persisting in the seed bank after fires.[13] With this, one study found seeds to persist in the seed bank up until 6 years after fire disturbance.[14] A study in Oklahoma found frequency of C. canadensis to peak at 2 years after fire disturbance, and to disappear from the community the next year.[19] Summer burns increase the frequency of C. canadensis rather than spring burns.[20]

Pollination and use by animals

Conyza canadensis was observed at the Archbold Biological Station to host ground-nesting bees such as Andrena fulvipennis (family Andrenidae), bees such as Epeolus carolinus (family Apidae), sweat bees such as Sphecodes heraclei (family Halictidae), wasps such as Leucospis affinis (family Leucospididae), spider wasps such as Episyron conterminus posterus (family Pompilidae), thread waisted wasps from the Sphecidae family such as Anacrabro ocellatus, Cerceris blakei, Ectemnius rufipes ais, Microbembex monodonta, Pluto rufibasis, Tachysphex apicalis, and T. similis, and wasps from the Vespidae family such as Pachodynerus erynnis, Parancistrocerus salcularis rufulus, Stenodynerus beameri, S. fundatiformis, and S. histrionalis rufustus.[21] Additionally, this species has been observed to host ground-nesting bees such as Calliopsis helianthi (family Andrenidae), aphids from the Aphididae family such as Aphis sp., Brachycaudus sp., Myzus sp., and Uroleucon sp., as well as ladybugs from the family Coccinellidae such as Coccinella septempunctata, Cycloneda munda, Harmonia axyridis, Hippodamia convergens, H. variegata, and Olla v-nigrum.[22] This species was also observed to host plasterer bees from the family Colletidae such as Hylaeus affinis and H. mesillae, sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as Agapostemon sericeus, A. texanus, A. virescens, A. aurata, Lasioglossum laevissimum, and L. pilosum, leafcutting bees from the family Megachilidae such as Heriades variolosa and Megachile brevis, treehoppers from the family Membracidae such as Campylenchia latipes, Entylia carinata, Micrutalis calva and Spissistilus festinus, plant bugs from the Miridae family such as Lygus lineolaris, Pseudatomoscelis seriatus, Slaterocoris stygicus and Spanagonicus albofasciatus, and cuckoo wasps from the family Chrysididae Anthomyiidae sp., Chrysididae sp., Crabronidae sp., and Ripiphoridae sp.[23] Flies of the Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) families have been collected from the flowers of C. canadensis.[24]

C. canadensis consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet for large mammals, but consists of approximately 10-25% of the diet for white-tailed deer.[25][26] The plant is a host for the tarnished plant bug (Lygus lineolaris) that is a pest for agricultural crops including alfalfa and cotton.

Diseases and parasites

It is a host for the viral disease aster yellows that is distributed to other plant individuals through leafhoppers.[3]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

C. canadensis is considered to be weedy or invasive in Kentucky, the Northeast, Nebraska and the Great Plains, the West, and Canada.[2] To combat this, mowing can reduce the spread of seeds through reducing seed production and dissemination in disturbed areas. Pulling or roguing can also be successful for small occurrences of the species. It has also been found to increase in density with a reduced tillage or no-till regiment. It has been reported that biotypes of C. canadensis are resistant to different herbicides, including Gramoxone (Paraquat), atrazine, the ALS (acetolactate synthase) family of herbicides, and glyphosate. It is much easier to control when the plant is less than 2 inches tall, and best time to control the species is between late fall and early spring. Using multiple herbicides together as a treatment can help combat against resistant biotypes.[3]

Cultural use

Historically, Native Americans utilized the species for numerous ailments. The Seminole tribe used it for cold and cough medicine, the Navajo and Chippewa tribes used it for stomach pain, and the Iroquois tribe used it to help combat fevers.[3] Other medicinal uses include as a stimulant, antispasmodic, and a nervine.[27]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 15 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Tilley, D. 2012. Plant Guide for Canadian horseweed (Conyza canadensis). USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Aberdeen, ID Plant Materials Center. 83210-0296.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ Ruth, A. D., et al. 2008. Seed bank dynamics of sand pine scrub and longleaf pine flatwoods of the Gulf Coastal Plain (Florida). Ecological Restoration 26:19-21.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: March 2019. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, L. Baltzell, D. E. Breedlove, Jane Brockmann, R. F. Christensen, Andre F. Clewell, M. R. Darst, J. P. Gillespie, Robert K. Godfrey, H. E. Grelen, D. W. Hall, D. Hazlett, Richard D. Houk, Jeffrey M. Kane, Lisa Keppner, Gary R. Knight, R. Komarek, R. Kral, O. Lakela, Robert L. Lazor, S. W. Leonard, Jose R. Martinez, Sidney McDaniel, Richard S. Mitchell, Elmer C. Prichard, Peter H. Raven, Paul L. Redfearn, Jr., Gary Schultz, Cecil R Slaughter, William R. Stimson, Victoria I. Sullivan, Bian Tan, and Alush Shilom Ton. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Bay, Brevard, Calhoun, Citrus, Clay, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Hamilton, Hillsborough, Jackson, Jefferson, Lake, Leon, Liberty, Monroe, Okaloosa, Orange, Palm Beach, Pinellas, Polk, Santa Rosa, St Johns, Suwannee, Taylor, Volusia, and Washington. Georgia: Thomas.

- ↑ Brewer, S. J., et al. (2012). "Do natural disturbances or the forestry practices that follow them convert forests to early-successional communities?" Ecological Applications 22: 442-458.

- ↑ Harrington, T. B. (2011). "Overstory and understory relationships in longleaf pine plantations 14 years after thinning and woody control." Canadian Journal of Forest Research 41: 2301-2314.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 8 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Dauer, J.T., Mortensen, D.A., and M.J. Vangessel. 2007. Temporal and spatial dynamics of long-distance Conyza canadensis seed dispersal. Journal of Applied Ecology. 44: 105-114.

- ↑ Cohen, S., et al. (2004). "Seed bank viability in disturbed longleaf pine sites." Restoration Ecology 12: 503-515.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Creech, M. N., et al. (2012). "Alteration and Recovery of Slash Pile Burn Sites in the Restoration of a Fire-Maintained Ecosystem." Restoration Ecology 20(4): 505-516.

- ↑ Leck, M. A. and C. F. Leck (1998). "A ten-year seed bank study of old field succession in central New Jersey." The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 125(1): 11-32.

- ↑ Looney, P. B. and D. J. Gibson (1995). "The Relationship between the Soil Seed Bank and Above-Ground Vegetation of a Coastal Barrier Island." Journal of Vegetation Science 6(6): 825-836.

- ↑ Mou, P., et al. (2005). "Regeneration strategies, disturbance and plant interactions as organizers of vegetation spatial patterns in a pine forest." Landscape Ecology 20: 971-987.

- ↑ Burton, J. A. (2009). Fire frequency effects on vegetation of an upland old growth forest in eastern Oklahoma. Environmental Science. Stillwater, Oklahoma, Oklahoma State University. Bachelor: 78.

- ↑ Penfound, W. T. (1968). "Influence of a wildfire in the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge, Oklahoma." Ecology 49: 1003-1006.

- ↑ Towne, E. G. and K. E. Kemp (2008). "Long-term response patterns of tallgrass prairie to frequent summer burning." Rangeland Ecology & Management 61: 509-520.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]

- ↑ Tooker, J. F., et al. (2006). "Floral host plants of Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) of central Illinois." Annals of the Entomological Society of America 99(1): 96-112.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Gee, K.L., M.D. Porter, S. Demarais, F.C. Bryant, and G.V. Vreede. 1994. White-tailed deer: Their foods and management in the Cross Timbers. Ardmore.

- ↑ Rafinesque, C. S. (1828). Medical flora; or Manual of the medical botany of the United States of North America.