Difference between revisions of "Clitoria mariana"

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

==Distribution== | ==Distribution== | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

| − | ===Habitat=== | + | ===Habitat=== |

| − | It occurs in frequently burned longleaf pine-turkey oak sandhills (FSU Herbarium), sand pine scrub (Greenberg 2003) | + | It occurs in frequently burned longleaf pine-turkey oak sandhills (FSU Herbarium), sand pine scrub (Entisols), <ref name=Greenberg> Greenberg, C. H. (2003). "Vegetation recovery and stand structure following a prescribed stand-replacement burn in sand pine scrub." Natural Areas Journal 23: 141-151. </ref> flatwoods (Spodosols) <ref name=bc03> Brewer, J. S. and S. P. Cralle (2003). "Phosphorus addition reduces invasion of a longleaf pine savanna (southeastern USA) by a non-indigenous grass (''Imperata cylindrica'')." Plant Ecology 167: 237-245. </ref> and upland longleaf pine-wiregrass communities (Ultisols), as well as the margins of mixed hardwood communities (FSU Herbarium) and loblolly pine plantations. <ref name=cushwa> Cushwa, C. T. (1966). The response of herbaceous vegetation to prescribed burning. Asheville, USDA Forest Service. </ref> It ranges from dry <ref name=wp> Walker, J. and R. K. Peet (1983). "Composition and species diversity of pine-wiregrass savannas of the Green Swamp, North Carolina." Vegetation 55: 163-179. <ref/> to moist sandy areas (FSU Herbarium). It can live in partially shaded areas (54% ambient light conditions). <ref name=Cathey> Cathey, S. E., L. R. Boring, et al. (2010). "Assessment of N2 fixation capability of native legumes from the longleaf pine-wiregrass ecosystem." Environmental and Experimental Botany 67: 444-450. </ref> It can be found in longleaf pine flatwoods communities. <ref name=bc03/> It is also found in loblolly pine communities. <ref name=cushwa/> It can also be found in sand pine scrub. <ref name=Greenberg/> It thrives in frequently burned areas, and typically occurs in high light environments, but also tolerates partial shade (FSU Herbarium). Although it occasionally occurs in frequently burned old-field communities, it is more typical of native pine communities which have minimal soil disturbance. Associated species include ''Desmodium nudiflorum, D. ochroleucum, Quercus laevis, Q. stellata, Pinus palustris, P. echinata, Centrosema virginianum, Carya tomentosa'', with other weeds, vines and trees in roadside ditches (FSU Herbarium). |

| − | |||

| − | It can be found in longleaf pine flatwoods communities | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Associated species include ''Desmodium nudiflorum, D. ochroleucum, | ||

===Phenology===<!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ===Phenology===<!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ||

Revision as of 09:01, 8 April 2016

| Clitoria mariana | |

|---|---|

| |

| photo by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Clitoria |

| Species: | C. mariana |

| Binomial name | |

| Clitoria mariana L. | |

| |

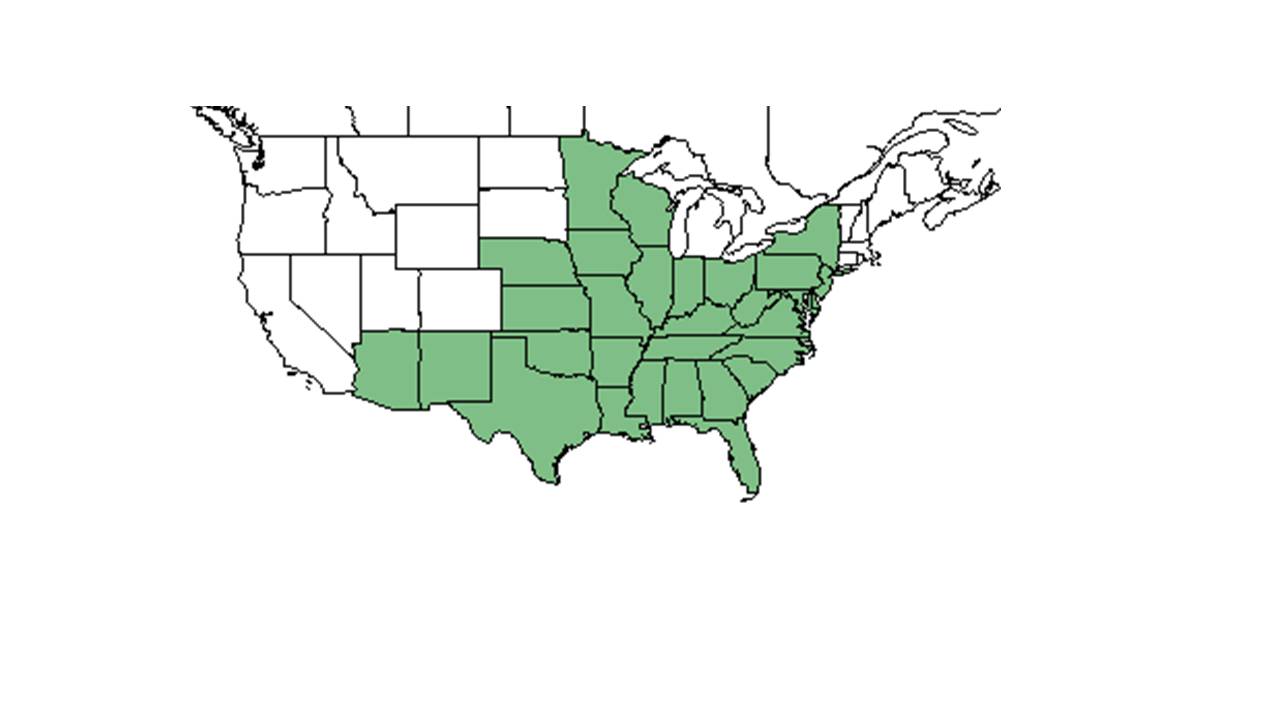

| Natural range of Clitoria mariana from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Atlantic pigeonwings

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonym: Martiusia mariana (L.) Small ITIS-Integrated Taxonomic Information System.gov

Description

It has a vining habit, where some are large vines whereas other are small erect plants (FSU Herbarium). It is paraheliotropic.[1]

Clitoria mariana is a trailing, twining, perennial, herbaceous vine growing up to 0.5-1 m long with glabrous to short-pubescent stems. The leaves are pinnately 3-foliolate. The leaflets are entire, mostly ovate to lanceolate or ovate-oblong to somewhat elliptic, growing 2-7 cm long; glabrous above and glabrous or occasionally short-pubescent beneath, stipellate; stipules ovate-lanceolate to lanceolate, ca. 2-4 mm long, tardily deciduous, striate. The racemes are axillary, peduncles growing 0.5-4(6) cm long, usually shorter than subtending leaves, are 1-3 flowered; pedicels are usually glabrous or rarely short-pubescent, (2) 4-10 mm long, each subtended by a triangular to lanceolate, striate bract growing 1-3 mm long and with a pair of linear bractlets growing3-6 mm long at or near the summits. The calyx is usually glabrous or rarely short-pubescent, somewhere bilabiate. The tube is cylindric, growing 1-14 cm long, upper lobes are widely triangular, acute, growing 4-6 mm long, lateral lobes ovate-lanceolate, acuminate, grwoing 5-7 mm long, lowermost lobe lanceolate, acuminate, growing 6-8 mm long. The petals are pale blue or lavender in color, the standard are spurless, growing 4-6 cm long, and 3-4 cm wide. The wing petals are smaller and attahced to the strongly incurved keel petals. The stamens are monadelphous. The legumes are flattened, oblong-linear, growing 3-6 cm long; stipe elongate, growing 1-2 cm long, valves longitudinally twisting upon dehiscence. The seeds are sticky and adherent (Radford 1964).

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

It occurs in frequently burned longleaf pine-turkey oak sandhills (FSU Herbarium), sand pine scrub (Entisols), [2] flatwoods (Spodosols) [3] and upland longleaf pine-wiregrass communities (Ultisols), as well as the margins of mixed hardwood communities (FSU Herbarium) and loblolly pine plantations. [4] It ranges from dry Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag It can be found in longleaf pine flatwoods communities. [3] It is also found in loblolly pine communities. [4] It can also be found in sand pine scrub. [2] It thrives in frequently burned areas, and typically occurs in high light environments, but also tolerates partial shade (FSU Herbarium). Although it occasionally occurs in frequently burned old-field communities, it is more typical of native pine communities which have minimal soil disturbance. Associated species include Desmodium nudiflorum, D. ochroleucum, Quercus laevis, Q. stellata, Pinus palustris, P. echinata, Centrosema virginianum, Carya tomentosa, with other weeds, vines and trees in roadside ditches (FSU Herbarium).

Phenology

It flowers from May to August and fruits from September to October (FSU Herbarium).

Seed dispersal

According to Kay Kirkman, a plant ecologist, this species disperses being carried externally by vertebrates. [5]

Fire ecology

Because it was found in Henley Park plots which were burned every one to two years in the winter, it is fire-tolerant (Brewer and Cralle 2003). It resprouts quickly after fire, which can be supported by the fact that it resprouted within a month after fire in Pavon's study (Pavon 1995). It attained its peak in two-year rough plots at Henley Park, plots that had undergone two growing seasons since the last burn (Brewer and Cralle 2003). This is supported by Greenberg's study, which shows the peak percent cover to be 16 months after fire around 80% (Greenberg 2003).

Use by animals

It is a game-food plant (Cushwa 1966), so it is probably consumed by Gopherus polyphemus (Gopher tortoise) white-tailed deer, and bobwhite quail (Hainds et al 1999).

Conservation and Management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

Brewer, J. S. and S. P. Cralle (2003). "Phosphorus addition reduces invasion of a longleaf pine savanna (southeastern USA) by a non-indigenous grass (Imperata cylindrica)." Plant Ecology 167: 237-245.

Cathey, S. E., L. R. Boring, et al. (2010). "Assessment of N2 fixation capability of native legumes from the longleaf pine-wiregrass ecosystem." Environmental and Experimental Botany 67: 444-450.

Cushwa, C. T. (1966). The response of herbaceous vegetation to prescribed burning. Asheville, USDA Forest Service.

Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Wilson Baker, R.K. Godfrey, William Reese, Paul Redfearn, Robert L. Lazor, R. Kral, C. Jackson, O. Lakela, Paul R. Fantz, James R. Burkhalter, Andre F. Clewell, Travis MacClendon, Karen MacClendon, R. A. Norris, Rodie White, Kevin Oakes, Delzie Demaree, John W. Thieret, Alex Lasseigne, L. J. Uttal, D. S. Correll, H. B. Correll, Norlan C. Henderson, James D. Ray, Jr., Charles S. Wallis, Bayard Long, F. S. Earle, C. F. Baker, R. L. Wilbur, Mary E. Wharton, Raymond Athey, W.C. Coker, A. B. Seymour, A. E. Radford, and Rachel Williamson. States and Counties: Florida: Calhoun, Collier, Escambia, Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Hernando, Jackson, Jefferson, Lafayette, Leon, Liberty, Okaloosa, Taylor, Wakulla, and Walton. Georgia: Coffee, Grady, McIntosh, Pike, and Thomas. Alabama: Lee. North Carolina: Pamlico, Wake, and Wilson. Arkansas: Conway, Garland, Pulaski, and Saline. Missouri: Carter, Douglas, McDonald. Louisiana: Caddo, and Jackson. Virginia: Alleghany, Montgomery, and Sussex. Texas: Callahan, Morris, Upshur, and Van Zandt. Mississippi: Tishomingo. Oklahoma: Latimer. New Jersey: Cape May. Kentucky: Livingston, and Nelson. South Carolina: Darlington.

Greenberg, C. H. (2003). "Vegetation recovery and stand structure following a prescribed stand-replacement burn in sand pine scrub." Natural Areas Journal 23: 141-151.

Hainds, M. J., R. J. Mitchell, et al. (1999). "Distribution of native legumes (Leguminoseae) in frequently burned longleaf pine (Pinaceae)-wiregrass (Poaceae) ecosystems." American Journal of Botany 86: 1606-1614.

Pavon, M. L. (1995). Diversity and response of ground cover arthropod communities to different seasonal burns in longleaf pine forests. Tallahassee, Florida A&M University.

Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 636. Print.

Walker, J. and R. K. Peet (1983). "Composition and species diversity of pine-wiregrass savannas of the Green Swamp, North Carolina." Vegetatio 55: 163-179.

- ↑ KMR observation in July on Pebble Hill Plantation, Georgia.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Greenberg, C. H. (2003). "Vegetation recovery and stand structure following a prescribed stand-replacement burn in sand pine scrub." Natural Areas Journal 23: 141-151.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Brewer, J. S. and S. P. Cralle (2003). "Phosphorus addition reduces invasion of a longleaf pine savanna (southeastern USA) by a non-indigenous grass (Imperata cylindrica)." Plant Ecology 167: 237-245.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Cushwa, C. T. (1966). The response of herbaceous vegetation to prescribed burning. Asheville, USDA Forest Service.

- ↑ Kay Kirkman, unpublished data, 2015.