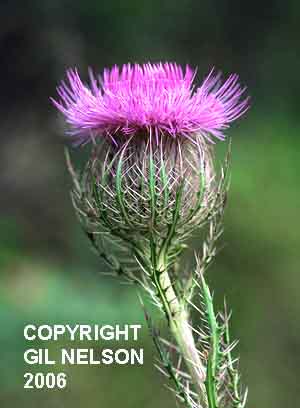

Cirsium horridulum

| Cirsium horridulum | |

|---|---|

| |

| photo by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Cirsium |

| Species: | C. horridulum |

| Binomial name | |

| Cirsium horridulum Michx. | |

| |

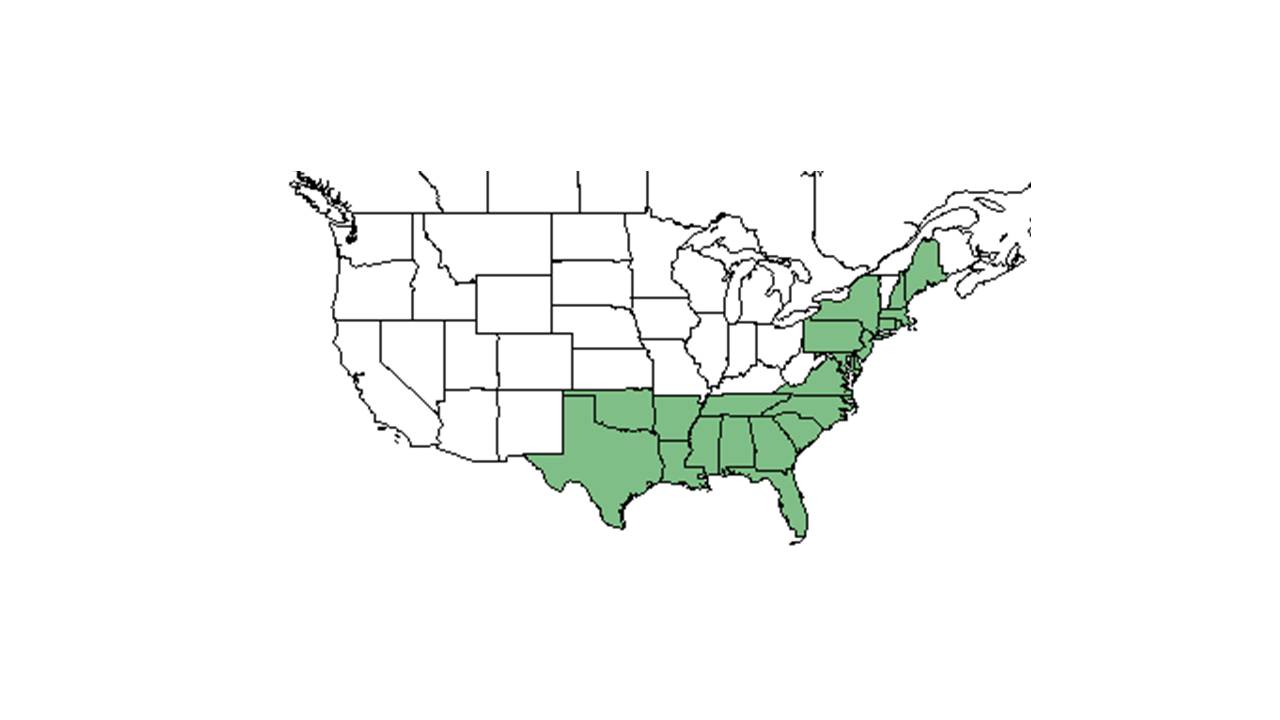

| Natural range of Cirsium horridulum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: yellow thistle, bigspine thistle, southern yellow thistle, bull thistle, pineland thistle

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Cardus spinosissimus Walter; Carduus smallii (Britton) H.E. Ahles[1]

Varieties: Cirsium horridulum Michaux var. horridulum; Cirsium horridulum Michaux var. megacanthum (Nuttall) D.J. Keil; Cirsium horridulum Michaux var. vittatum (Small) R.W. Long; Cirsium horridulum var. elliottii Torrey & A. Gray; Cirsium vittatum Small; Cirsium smallii Britton[1]

Description

A description of Cirsium horridulum is provided in The Flora of North America.

This species tends to resprout growing erect to about 1 meter,[2]

There are three varieties: horridulum, magacanthum, and vittatum. Var. horridulum is the only variety with yellow flowers, but it may also have red and purple flowers[3] topped with a dense rosette of spiny leaves that can be upwards of a foot in length.[4]

Distribution

C. horridulum is found in all the eastern coastal states from Maine to Texas, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. [5] The varieties may have differing ranges: variety C. horridulum is found throughout the species range, except Oklahoma and Arkansas, variety C. megacanthum is found only in the lower Piedmont and coastal plain, and the variety C. vittatum is isolated to the coastal plain. [3]

Ecology

Habitat

Cirsium horridulum is considered a facultative upland species that usually is found in non-wetland ecosystems, but can grow in wetlands as well.[6] Known habitats include pine-wiregrass woodlands, savannahs, pine-scrub oak woodlands, juniper-pine-palm woodlands, longleaf pine-turkey oak barrens, pine hills, cabbage palm hammocks, and along streams and marshes. This species has also been observed in human disturbed habitats such as roadsides, weedy fields, waste grounds, ligand fields, flat spoil areas, shallow watered ditches, pine plantations, and frequently mowed areas.

This plant takes to the moister soil below longleaf pine-scrub oak forested sand hills and occurs in open light conditions in loamy sand or peat, loose sand, and drying loamy sand. Usually inhabits moist open areas between either drier or wetter conditions and may be present in well-drained uplands and limestone substrate.[2]

Associated species include Pinus palustris, Quercus laevis, Melanthera, Eleocharis, Juncus, Xyris, and others. [2]

Phenology

This species has been observed flowering from March to October and fruiting from March through November. [2] The varieties may flower at different times: variety C. horridulum flowers April to June and September with peak inflorescence in April, variety C. megacanthum flowers March to June and variety C. vittatum flowers from February to August. [3][7] Kevin Robertson has observed this species flower within three months of burning. KMR The variety C. horridulum has produced natural hybrids with C. pumilum var. pumilum. [3]

Seed dispersal

Seeds are cypsela that are wind and bird dispersed. [3] This species is thought to be dispersed by wind. [8]

Fire ecology

This species is able to grow in burned old fields.[2] One study found C. horridulum to be most frequent in response to summer seasonality burns, rather than winter and spring burns.[9]

Pollination

Cirsium horridulum was observed to host a range of species at the Archbold Biological Station. These observations included bees such as Apis mellifera (family Apidae), sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as Augochlorella gratiosa, Halictus poeyi, Lasioglossum nymphalis and L. pectoralis, as well as leafcutting bees from the Megachilidae family such as Lithurgus gibbosus and Megachile brevis pseudobrevis.[10] Other pollinators in the Hymenoptera order observed to pollinate this species include Dialictus nymphalis, Eulaeus pectoralis, Halictus ligatus, and Osmia chalybea.[11][12] Additionally, this species has been observed to host sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as Agapostemon virescens, Halictus ligatus and Lasioglossum coriaceum, as well as leafcutting bees such as Coelioxys rufitarsis (family Megachilidae), and bees from the Apidae family such as Anthophora occidentalis and Bombus bimaculatus.[13] C. horridulum is considered to be of special value to native bees since it attracts large numbers for pollination.[14]

Herbivory and toxicology

C. horridulum comprises approximately 5-10% of the diet for terrestrial birds[15] including the American Goldfinch and Carolina Chickadee.[16] This species is the larval host to the little metalmark (Calephelis virginiensis) and painted lady (Vanessa cardui) butterflies.[17] This species also provides nesting materials and structure for various native bees.[14]

Diseases and parasites

The leaf epidermis is surrounded by an internal and external cuticle, which reduces the likelihood of a pathogen entering the plant. [18]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

C. horridulum is listed as an endangered species by the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection, the New Hampshire Division of Forests and Lands, and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. It is also listed as threatened by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management. This species is considered a noxious weed by the Arkansas State Plant Board, and the Iowa Department of Agricultire and Land Stewardship.[6]

Cultural use

Members of the Seminole Tribe have been said to use parts of this plant to make blowgun darts.[19] Medicinally, the root and leaves were soaked with whiskey and drunk in order to clear the lungs and throat from phlegm, and it is a strong astringent. The white heart of the plant can be eaten raw.[20]

The leaves and stems can be cooked, so keeping it as a potherb is a possibility.[21]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: L. C. Anderson, G. R. Cooley, J. R. Eaton, R. K. Godfrey, E. Keppner, L. Keppner, R. Kral, H. Kurz, K. MacClendon, K. M. Meyer, K. Patel, P. L. Redfearn Jr., W. R. Stimson, A. Townesmith, L. B. Trott, K. L. Tyson, and C. E. Wood Jr. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Dade, Dixie, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Marion, Monroe, Pasco, Polk, Taylor, Wakulla, and Washington. Georgia: Grady and Thomas.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 [[1]]Encyclopedia of Life. Accessed: April 14, 2016

- ↑ Denhof, Carol. 2021. Plant Spotlight Cirsium horridulum Michx. Yellow Thistle Aster Family - Asteraceae. The Longleaf Leader. Vol. XIII, Issue 4. Pg. 7

- ↑ [[2]]U.S. Wildflowers. Accessed: April 14, 2016

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 5 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 7 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Deyrup, M. J. E., and Beth Norden (2002). "The diversity and floral hosts of bees at the Archbold Biological Station, Florida (Hymenoptera: Apoidea)." Insecta mundi 16(1-3).

- ↑ Hall, H. G. a. J. S. A. (2010). "Surveys of bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila) in natural areas of Alachua County in north-central Florida." The Florida Entomologist 93(4): 609-629.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [3]

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 [[4]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 5, 2019

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Denhof, Carol. 2021. Plant Spotlight Cirsium horridulum Michx. Yellow Thistle Aster Family - Asteraceae. The Longleaf Leader. Vol. XIII, Issue 4. Pg. 7

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedfnps - ↑ Pesacreta, T. C. and K. H. Hasenstein (1999). "The Internal Cuticle of Cirsium horridulum (Asteraceae) Leaves." American Journal of Botany 86(7): 923-928.

- ↑ name="fnps">[[5]]Florida Native Plant Society. Accessed: April 14, 2016

- ↑ Speck, F. G. (1941). "A list of plant curatives obtained from the Houma Indians of Louisiana." Primitive Man 14(4): 49-73.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.