Centella asiatica

Common name: Spadeleaf [1]; Centella [2]; Coinleaf [2]

| Centella asiatica | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Apiales |

| Family: | Apiaceae |

| Genus: | Centella |

| Species: | C. asiatica |

| Binomial name | |

| Centella asiatica L. Urb. | |

| |

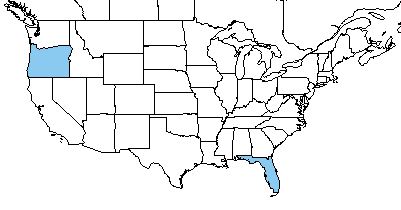

| Natural range of Centella asiatica from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Centella erecta (Linnaeus f.) Fernald; Centella repanda (Persoon) Small.[3]

Varieties: none.[3]

Description

C. asiatica is a perennial forb/herb or subshrub of the Apiaceae family native to the Pacific Basin, excluding Hawaii. [1]

Distribution

While native to the Pacific Basin, C. asiatica has been introduced in the United States in Hawaii, Oregon, and Florida.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

C. asiatica is a facultative wetland species[1] and is found in savannas, pondshores, ditches, and a wide variety of other moist to wet habitats.[2][4]

C. asiatica increased its crown cover and biomass in response to heavy silvilculture in North Florida. It has also shown additional regrowth in reestablished pine flatwoods that were disturbed by silvilculture,[5] and increased its frequency in response to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests. Additionally, it has shown positive regrowth in reestablished native flatwoods that were disturbed by clearcutting and chopping.[6]

Associated species include Xyris isoetifolia, Hypericum lissophloeus, Hypericum sp., Rhexia salicifolia, Taxodium distichum, Fraxinus profunda, Quercus laurifolia, Polygala lutea, Pluchea baccharis, Sarracenia flava, and Proserpinaca pinnata.[4]

Phenology

C. asiatica has been observed flowering from April to August as well as September and October.[7][4] It has been observed fruiting in August, October, and November.[4]

Seed bank and germination

Seed germination is greatest in low dunes, dry and wet swales, and marsh spoils.[8] It is prevalent in seed banks where it is found.[9]

Fire ecology

A study found C. asiatica to significantly increase in frequency in response to multiple disturbances, including burning, clearcutting, stump removal, shearing and piling, and discing in north Florida.[10]

Herbivory and toxicology

In some Asian countries, C. asiatica is a host plant for the false spider mite (Brevipalpus californicus).[11]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

The leaves are used pharmaceutically as an anti-inflammatory and as a diuretic.[12] It is also medicinally known to be aromatic, a narcotic, and used against leprosy.[13]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 USDA Plant Database https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=CEAS

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Ann F. Johnson, Cecil R. Slaughter, Dianne Hall, Kim Ponzio, Loran C. Anderson, R.F. Doren, Robert K. Godfrey, R. Kral, M. Darst, H. Light, L. Peed. States and counties: Washington County Florida, Indian River County Florida, Brevard County Florida, Gulf County Florida, Wakulla County Florida, Leon County Florida, Thomas County Georgia, Jackson County Florida, Covington County Alabama, Gadsden County Florida, Dixie County Florida.

- ↑ Conde, L.F., B.F. Swindel, and J.E. Smith. (1986). Five Years of Vegetation Changes Following Conversion of Pine Flatwoods to Pinus elliottii Plantations. Forest Ecology and Management 15(4):295-300.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 18 MAY 2018

- ↑ Looney, P. B. and D. J. Gibson (1995). "The Relationship between the Soil Seed Bank and Above-Ground Vegetation of a Coastal Barrier Island." Journal of Vegetation Science 6(6): 825-836.

- ↑ Poiani, K. A. and P. M. Dixon (1995). "Seed banks of Carolina bays: potential contributions from surrounding landscape vegetation " American Midland Naturalist 134: 140-154

- ↑ Conde, L. F., et al. (1983). "Plant species cover, frequency, and biomass: Early responses to clearcutting, burning, windrowing, discing, and bedding in Pinus elliottii flatwoods." Forest Ecology and Management 6: 319-331.

- ↑ Childers, C. C., et al. (2003). "Host plants of Brevipalpus californicus, B. obovatus, and B. phoenicis (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) and their potential involvement in the spread of viral diseases vectored by these mites." Experimental & Applied Acarology 30: 29-105.

- ↑ Akbar, K. F. and M. Athar. (2006). "Taxonomy and conservation of medicinal plants in canal-irrigated areas of Punjab, Pakistan." SIDA 22(1): 593-606.

- ↑ Nickell, J. M. (1911). J.M.Nickell's botanical ready reference : especially designed for druggists and physicians : containing all of the botanical drugs known up to the present time, giving their medical properties, and all of their botanical, common, pharmacopoeal and German common (in German) names. Chicago, IL, Murray & Nickell MFG. Co.