Carya illinoinensis

Common name: pecan [1]

| Carya illinoinensis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Juglandales |

| Family: | Juglandaceae |

| Genus: | Carya |

| Species: | C. illinoinensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Carya illinoinensis Wangen. | |

| |

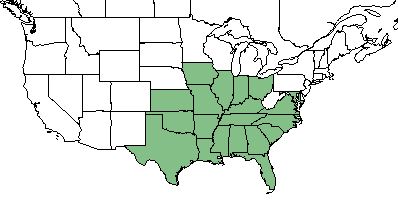

| Natural range of Carya illinoinensis from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Carya illinoensis[2]

Varieties: Hicoria pecan (Marshall) Britton; Hicoria texana LeConte[2]

Description

C. illinoinensis is a perennial tree of the Juglandaceae family native to North America[1] that can reach heights between 100 - 140 feet. Pecan is a medium to large deciduous tree with alternately arranged, pinnately compound leaves that have 11 - 17 leaflets each between 4 - 8 inches long. This species possesses unisexual flowers, which are located in separate clusters on the same tree. The fruit is a thin-shelled nut that grows in clusters of 3 - 12, four winged from the base to the apex, and brown in color with yellow scales. The husk is thin and can persist on branches into winter, while the nut is thin-shelled, reddish-brown, and pointed on each side. The bark can be light or grayish brown, and is shallowly furrowed and flat ridged.[3]

Distribution

C. illinoinensis can be found in the southeastern corner of the United States.[1] Originally, pecan trees were native to the south-central U.S., but spread into the southeastern region due to cultivation.[4] Additionally, it is thought that the Native Americans have spread the overall range of the species through planting.[5]

Ecology

Habitat

C. illinoinensis is found in bottomlands, suburban woodlands, rural forest edges and floodplains, disturbed areas, and is commonly cultivated around dwellings and in orchards. It also commonly naturalizes near where cultivated trees are located.[4][6] It grows on moist and rich soils that are well-drained, and soils that are not subjected to continued flooding.[3] It can be found in upland pinelands that are managed with frequent fire in north Florida and south Georgia, but it is not native.[7]

Associated species: Quercus sp., Pinus sp., Carya sp., Albizia sp., Melia sp., Prunus laurocerasus, and Cinnamomum camphora.[6]

Phenology

C. illinoinensis has been observed to flower in May, and fruit in September.[6] Common flowering time is between March and May.[5]

Seed bank and germination

Seeds of C. illinoinensis have a delayed germination and require cold stratification for propagation. They should be stratified between 36-41 degrees Fahrenheit for 30-60 days, which should then be followed by an incubation at room temperature. Best time to plant seeds is between December and February.[3]

Fire ecology

C. illinoinensis is not fire resistant, and has a low fire tolerance.[1] It is especially susceptible to fire damage due to the bark having low insulating capacity. Once a fire occurs, re-colonization happens through the seeds being dispersed to the site by water and animals.[3]

Herbivory and toxicology

C. illinoinensis has been observed to host planthoppers from the Acanaloniidae family such as Acanalonia bivittata and Acanalonia conica, aphids such as Aphis sp. (family Aphididae), froghoppers such as Prosapia bicincta (family Cercopidae), leafhoppers such as Alebra aurea (family Cicadellidae), cicadas such as Tibicen lyricen (family Cicadidae), spittle bugs from the Clastopteridae family such as Clastoptera proteus and Clastoptera obtusa, leaf-footed bugs from the Coreidae family such as Leptoglossus oppositus and L. phyllopus, treehoppers from the Membracidae family such as Carynota mera, Cyrtolobus tuberosus, Cyrtolobus sp., Enchenopa binotata, Entylia sp., Spissistilus festinus, Telamona monticola, Telamona unicolor, Telamona sp. and Vanduzea arquata, plant bugs from the Miridae family such as Ceratocapsus sp., Lygus lineolaris, Plagiognathus albatus, P. fuscosus and P. sp., stink bugs from the Pentatomidae family such as Acrosternum hilare, Murgantia histrionica, Parabrochymena arborea and Podisus maculiventris, assassin bugs from the Reduviidae family such as Arilus cristatus, Zelus luridus and Zelus sp., and true bugs such as Paromius longulus (family Rhyparochromidae).[8]

C. illinoinensis is not highly palatable to grazing or browsing animals, but is highly palatable to humans.[1] For wildlife, C. illinoinensis is used quite extensively. White-tailed deer browse on seedling and older trees' lower branches, nuts are eaten by various birds, raccoons, opossums, and squirrels, and the tree as a whole provides cover for various mammals and birds.[3] It is a larval host for the gray hairstreak butterfly (Strymon melinus), and one of the only few plants the walnut caterpillar (Datana integerrima) feeds on.[5][9] Stenosphenus notatus, a species of beetle, breeds in the dead limbs of this species and other hickories.[10]

Diseases and parasites

Pests that attack the nut include the pecan nut casebearer (Acrobasis nuxvorella), the pecan weevil (Curculio caryae), and the hickory shuck worm (Cydia caryana). A disease that can affect the plant is pecan scab, which can be caused by the fungus Fusicladium effusum.[11] It is a preferred host of the Elm Spanworm (Ennomos subsignarius), the Fall Webworm (Hyphantria cunea), and the Hickory Bark Beetle (Scolytus quadrispinosus).[9] C. illinoinensis is a host plant for American mistletoe (Phoradendron leucarpum), Combleaf seymeria (Seymeria pectinata), and Fascicled gerardia (Agalinis fasciculata).[12][13][14]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

For management, little pruning is necessary for C. illinoinensis since it forms a natural vase-shaped canopy; only management necessary is removing diseased, broken, or dead limbs as often as needed. However, pecan trees are susceptible to a zinc deficiency, which can be compensated by spraying the trees each 2-4 weeks in spring and early summer with zinc sulfate.[3] C. illinoinensis is a highly cultivated plant due to its use by humans as food.[4] These cultivars are available for variation in disease resistance, nut production, and various adaptability. Cultivars named by the USDA Agricultural Research Service are named after Native American tribes.[11]

Cultural use

The tree produces edible nuts for humans, and oil extracted from the nuts is used for cosmetics and cooking. Milk can also be extracted from the nut for various uses, and the wood is used occasionally for furniture, flooring, paneling, and cabinetry. Historically, Native American tribes used C. illinoinensis for multiple medical ailments. The Comanche tribe used pecan as a treatment for ringworm by pulverizing the leaves and rubbing this on the effected area. The Kiowa tribe created a decoction to consume for treatment of tuberculosis from the bark of the tree.

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 USDA Plant Database https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=CAIL2

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Moore, L. M. (2006). Plant Guide: Pecan Carya illinoinensis. N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture. Baton Rouge, LA.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 1, 2019

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Bob Farley, and R.K. Godfrey. States and counties: Florida: Franklin, Leon, Gadsden, Jefferson, Jackson, Liberty, Washington, Holmes, and Madison.

- ↑ Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson (2007). A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, south Georgia, USA. Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems, Tallahassee, Tall Timbers Research Station.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 USDA Forest Service (1989). Insects and diseases of trees in the South. USDA Forest Service, Atlanta, GA. Protection Report R8-PR 16. F. S. S. Region: 98.

- ↑ Fisher, W. S. (1946). "Entomology - Synopsis of the cerambycid beetles of the genus Stenosphenus Haldeman found in America, north of Mexico." Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences 36(3): 86-94.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Stevens, J. (2012). Plant Fact Sheet: Pecan Carya illinoinensis. N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture. Nacogdoches, TX.

- ↑ Musselman, L. J. (1996). "Parasitic weeds in the southern United States." Castanea 61: 271-292.

- ↑ Musselman, L. J. and W. F. Mann, Jr (1978). Root parasites of southern forests. , USDA Forest Service, Southern For. Exp. Station, New Orleans, LA. Gen. Tech. Rpt. SO-20. : 76.

- ↑ Musselman, L. J. and W. F. Mann, Jr (1979). "Agalinis fasciculata (Scrophulariaceae), a native parasitic weed on commercial tree species in the southeastern United States." American Midland Naturalist 101: 459-464.