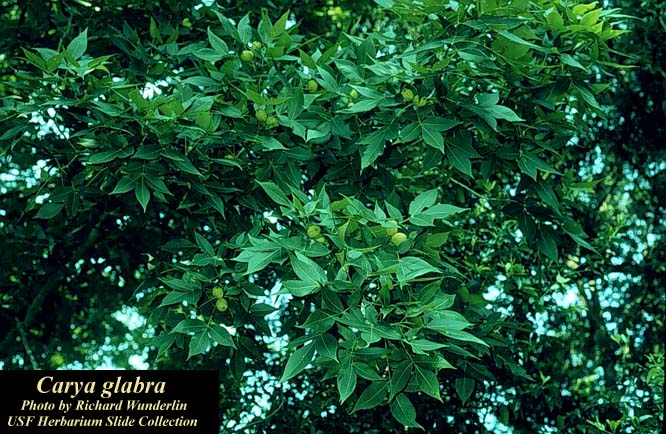

Carya glabra

Common name: pignut hickory [1]

| Carya glabra | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Juglandales |

| Family: | Juglandaceae |

| Genus: | Carya |

| Species: | C. glabra |

| Binomial name | |

| Carya glabra Mill. | |

| |

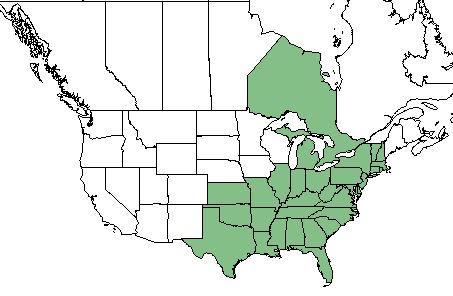

| Natural range of Carya glabra from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Carya glabra var. glabra[2]

Varieties: Carya ovalis (Wangenheim) Sargent var. hirsuta (W.W. Ashe) Sargent; Hicoria glabra (P. Miller) Britton var. glabra; Hicoria glabra (P. Miller) Britton var. hirsuta W.W. Ashe; Hicoria austrina Small[2]

Description

C. glabra is a perennial tree of the Juglandaceae family native to North America and Canada[1] that can reach heights of 50 - 100 feet; this large tree has short picturesque branches, a spreading crown, and coarsely textured bark. The leaves are pinnately compound, which turn golden-yellow in color in the fall.[3]

Distribution

C. glabra is found in the southeastern corner of the United States, as well as the Ontario region of Canada. [1]

Ecology

Habitat

C. glabra is found in a wide variety of forests and woodlands, but most often non-wetland areas.[4] It has been observed along moist roadsides, old fields, scrub, hammocks, hardwood bluffs, floodplains, and riverbanks. Soils include red sandy soil, sandy soil, loamy soil, and loamy sand.[5] It is considered to be associated with the longleaf pine forest ecosystem, and is a characteristic species of the shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands community.[6][7]

Associated species: Pinus clausa, Pinus sp., Quercus ilex, Quercus virginiana, Quercus geminata, Quercus laurifolia, Quercus sp., Magnolia sp., Sabal palmetto, Liquidambar styraciflua, Fagus sp., Celtis sp., Aesculus sp., Bumelia sp., Juniperus sp., Carya sp., Ilex opaca, and Persea borbonia.[5]

Phenology

C. glabra has been observed flowering February through December with peak inflorescence in April and September. [8]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates. [9]

Seed bank and germination

For propagation, it is easiest to sow seeds immediately after collecting or to stratify them and sow in the spring. To overcome embryo dormancy, moist stratification should be conducted between 33-40 degrees for 30-150 days; older seeds need less stratification.[3]

Fire ecology

C. glabra is not fire resistant, but has a medium fire tolerance,[1] and populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[10] A study by Clewell found that fire exclusion on a once annually burned upland pine woodland let pignut hickory colonize the unit.[11] However, it can still be found in areas that are regularly burned as well.[12] C. glabra has been shown to increase in frequency in annually burned areas than unburned areas.[13] As well, stem density has been shown to increase with application of prescribed fire.[14]

Herbivory and toxicology

Carya glabra has been observed to host planthoppers such as Synecdoche impunctata (family Achilidae) and Thionia simplex (family Issidae), leafhoppers from the family Cicadellidae such as Eratoneura acantha and E. parva, true bugs such as Cedusa sp. (family Derbidae), and treehoppers from the family Membracidae such as Carynota mera, C. fuliginosus, Smilia camelus and Telamona unicolor[15] C. glabra is not highly palatable to grazing or browsing animals, but is highly palatable to humans.[1] It is a food source for songbirds and small mammals, and serves as a larval host for Actias luna (family Saturniidae), Acronicta funeralis (family Noctuidae), and Citheronia regalis (family Saturniidae). It is also a food source for white-tailed deer.[16]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

In addition to the nuts being edible raw, Native Americans would use the tree for all sorts of culinary resources. Members of the Carya genus have a sap that makes an excellent syrup, the nuts can be boiled in order to make a butter from the oil that comes off and then the meat can be eaten or preserved. The oil butter or gravy could be used as a spread on food, or it could be utilized as a hair oil.[17]

The word "hickory" comes from the native peoples who would make this oil; they were known as the powcohicora people, which white settlers shortened to hickory.[18]

The wood is used for broom handles, tool handles, sport implements, and skis.[3]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 1, 2019

- ↑ Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: L. B. Trott, Donald E. Stone, H. Kurz, L. Baltzell, A. F. Clewell, S. W. Leonard, - Thompson, Robert K. Godfrey, Patricia Elliot, Loran C. Anderson, K. Craddock Burks, D. B. Ward, D. Burch. States and counties: Wakulla County Florida, Escambia County Florida, Liberty County Florida, Marion County Florida, Madison County Florida, Franklin County Florida, Walton County Florida, Santa Rosa County Florida, Leon County Florida, Gadsden County Florida, Hernando County Florida, Taylor County Florida, Okaloosa County Florida, Jefferson County Florida, Suwannee County Florida, Hamilton County Florida, Hardee County Florida, Levy County Florida, Sarasota County Florida, Columbia County Florida

- ↑ Brockway, D. G., et al. (2005). Restoration of longleaf pine ecosystems. F. S. United States Department of Agriculture, Southern Research Station.

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2013). "Prior prevalence of shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands in the Tallahassee red hills." Castanea 78(4): 266-276.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 17 MAY 2018

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2014). "Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida." Castanea 79: 147-167.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., et al. (2012). "Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station." Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Hutchinson, T. F., et al. (2005). "Prescribed fire effects on the herbaceous layer of mixed-oak forests." Can. J. For. Res 35: 877-890.

- ↑ Taft, J. B. (2003). "Fire effects on community structure, composition, and diversity in a dry sandstone barrens." Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 130: 170-192.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]

- ↑ Atwood, E. L. (1941). "White-tailed deer foods of the United States." The Journal of Wildlife Management 5(3): 314-332.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.