Baccharis halimifolia

| Baccharis halimifolia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John R. Gwaltney, Southeastern Flora.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Baccharis |

| Species: | B. halimifolia |

| Binomial name | |

| Baccharis halimifolia L. | |

| |

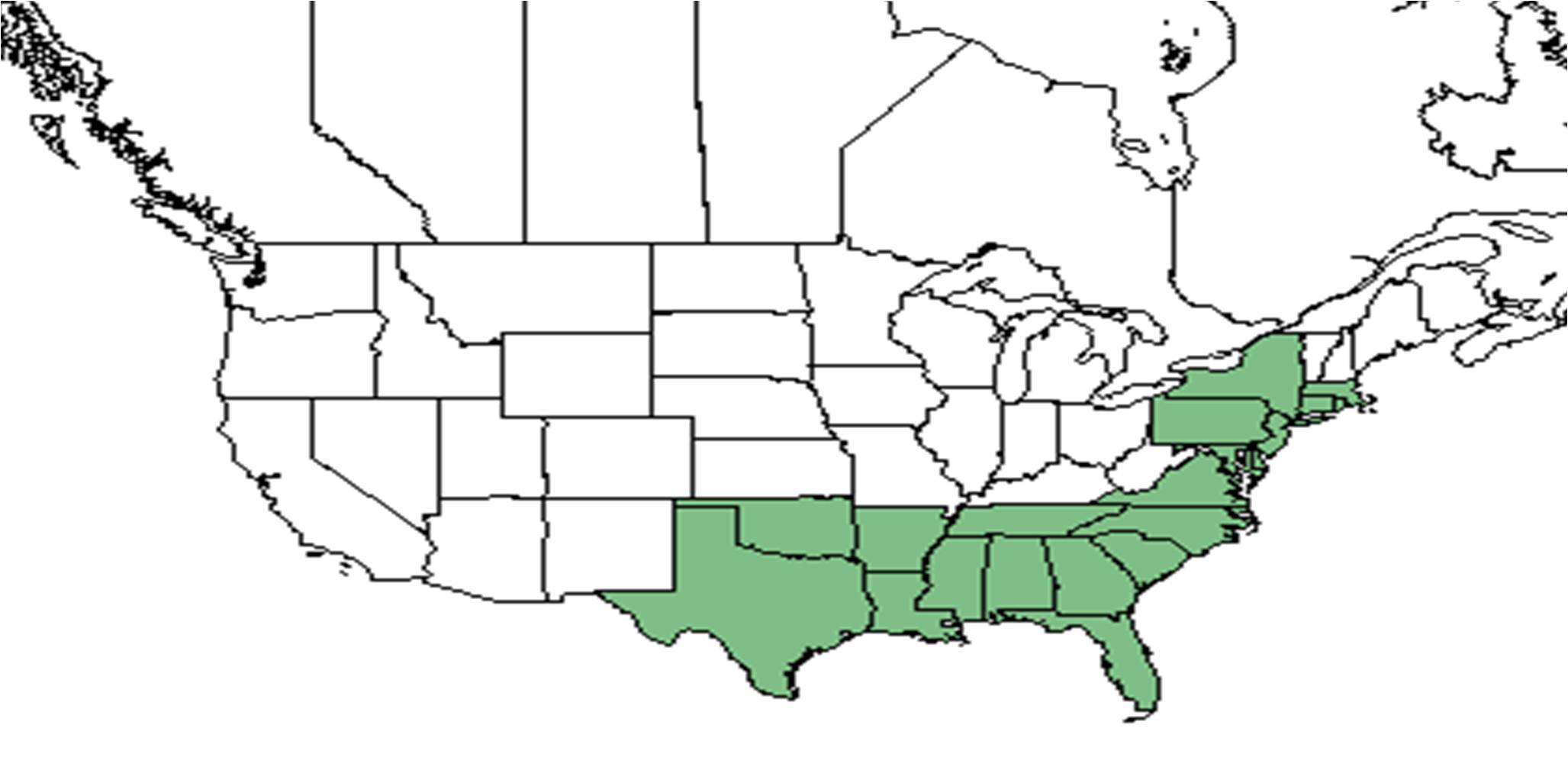

| Natural range of Baccharis halimifolia from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Eastern Baccharis; Silverling; High-tide Bush; Mullet Bush; Groundsel Tree

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonym: Baccharis halimifolia var. angustior de Candolle The Flora of North America.

Description

A description of Baccharis halimifolia is provided in The Flora of North America.

Baccharis genus are dioecious, glabrous shrubs. They are rarely small trees. The leaves are alternate, fleshy, toothed or entire. The heads pedunculated or sessile, most of the time in 3-5 glomerules. The involucres are cylindric, 4-5 mm long, 2.5-3.5 mm broad. The bracts are imbricate, sometimes purplish in color, and obtuse. The flowers are discoid and yellowish in color. The nutlets are tan in color, lustrous, cylindric, 10-ribbed, glabrous, and 1.2-1.5 mm long. The pappus bristles are white to tan in color. The capillary is 7-10 mm long.[1] Specifically for B. halimifolia, is a shrub, growing to approximately 1-4 m tall. The leaves are elliptic to obovate, rarely ovate; are coarsely serrate but mostly towards the apex, rarely entire. The leaves grow 3-7 cm long and 1-4 cm wide. The petioles are 5-12 mm long. The involucres are mostly in pedunculated glomerules. [1]

Distribution

B. halimifolia is native to the southeastern United States, from Texas to Virginia, and portions of the northeast including New York and Massachusetts.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

It is native to brackish and fresh marshes and marsh borders, moist abused land, ditches, roadsides and other disturbed areas, and hammocks.[3] It has also been observed in dry open slopes, moist loamy sand and loamy clay sand, shrub thickets, flatwoods, swamps, floodplain forests, and shores.[4] It is associated with the longleaf pine forest ecosystem.[5] One study in Mississippi found B. halimifolia to be limited to areas of higher elevation in an alluvial valley.[6]

B. halmifolia responds positively and negatively to soil disturbance by roller chopping and a KG blade in East Texas Loblolly Pine-Hardwood Forests.[7]

Associated species: Panicum virgatum, Juncus roemerianus, Solidago sempervirens, Myrica sp., Iva sp., Hudsonia sp., Fimbristylis sp., Spartina sp., Ilex opaca, Rhus copallina, Bidens sp., Polygonum sp., Cyperus sp., Ludwigia sp., and Baccharis angustifolia.[4]

Phenology

B. halimifolia has been observed to flower in February and between September to December.[8]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind.[9][6]

Fire ecology

It was observed in a burned over wiregrass, slash pine, and Magnolia virginiana bay.[4] As well, one study found the rootstock density of B. halimifolia to be significantly greater in burned treatments rather than unburned treatments.[10]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Baccharis halimifolia' at Archbold Biological Station. [11]

Apidae: Apis mellifera

Apidae: Bombus impatiens

Colletidae: Colletes mandibularis, C. simulans, C. thysanellae

Halictidae: Agapostemon splendens, Augochlora pura, Augochlorella aurata, Augochloropsis metallica, Halictus poeyi, Lasioglossum miniatulus, L. nymphalis, L. puteulanum, Sphecodes heraclei

Leucospidae: Leucospis affinis

Leucospididae: Leucospis affinis, L. robertsoni, L. slossonae

Pompilidae: Anoplius atramentaius, A. parsoni, Episyron conterminus posterus, Poecilopompilus algidus, P. interruptus

Sphecidae: Bicyrtes quadrifasciata, Cerceris blakei, C. flavofasciata floridensis, C. tolteca, Ectemnius decemmaculatus tequesta, E. rufipes ais, Larra bicolor, Oxybelus decorosum, O. laetus fulvipes, Palmodes dimidiatus, Philanthus ventilabris, Tachytes distinctus, T. floridanus, T. pepticus, T. validus

Vespidae: Pachodynerus erynnis, Parancistrocerus salcularis rufulus, Polistes bellicosus, P. dorsalis hunteri, P. fuscatus, P. metricus, P. perplexus, Stenodynerus beameri, S. fundatiformis, S. lineatifrons, Vespula squamosa, Zethus slossonae, Zethus spinipes

Other species known to pollinate B. halimifolia include Dialictus miniatulus, D. nymphalis, and Halictus ligatus.[12]

Use by animals

While the leaves on this plant are poisonous to livestock, marsh wrens and small birds use the openly branched and brittle stems for nests. The baccharis foliage feeding beetle (Trirhabda baccharidis) is a well known beetle to help keep Baccharis populations in check.[13] As well, it consists of 2-5% of the diet of large mammals and terrestrial birds;[14] studies have found B. halimifolia to be eaten by the Florida marsh rabbit and white-tailed deer.[15][16] Historically, it has been used by humans as a palliative and demulcent in consumption and cough, and the root was made into a strong decoction that could be drunk several times a day.[17]

Conservation and management

It is listed as rare by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.[2]

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 635-6. Print

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 26 March 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: March 2019. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Eduard Baltars, Fred A. Barkley, Robert Blaisdell, H. L. Blomquist, Steve Boyce, J. John Brady, D. Burch, K. Craddock Burks, R. S. Campbell, A. F. Clewell, George R. Cooley, Tom Daggy, Delzie Demaree, Joseph Ewan, E. S. Ford, William B. Fox, Douglas Gage, J. P. Gillespie, Robert K. Godfrey, A. E. Hammond, S. B. Jones, R. Komarek, R. Kral, H. Kurz, O. Lakela, Robert L. Lazor, Robert J. Lemaire, Sidney McDaniel, Richard S. Mitchell, D. E. Moreland, John Morrill, R. A. Norris, G. S. Ramseur, William Reese, Annie Schmidt, Lloyd H. Shinners, B. R. Sinor, T. E. Smith, B. C. Tharpe, John W. Thieret, D. B. Ward, Erdman West, Andrew W. Westling, Roomie Wilson, and D. R. Windler. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Collier, Franklin, Gilchrist, Gulf, Hernando, Hillsborough, Indian River, Jackson, Jefferson, Lee, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Manatee, Monroe, Nassau, Okaloosa, Palm Beach, Putnam, Santa Rosa, Sarasota, Taylor, and Wakulla. Georgia: Clinch, Grady, and Thomas. Mississippi: Covington, Franklin, Jackson, Leake, Neshoba, and Newton. Louisiana: Calcasieu, Jackson, Jefferson Davis, Lafayette, Plaquemines, St Bernard, Tangipahoa, and Vermillion. Maryland: Baltimore and Worcester. Alabama: Baldwin. Arkansas: Bradley, Clark, and Lafayette. North Carolina: Alamance, Bladen, Durham, Martin, Northampton, and Wake. Texas: Gonzales, Gregg, and Van Zandt.

- ↑ Brockway, D. G., et al. (2005). Restoration of longleaf pine ecosystems. F. S. United States Department of Agriculture, Southern Research Station.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Battaglia, L. L., et al. (2002). "Sixteen years of old-field succession and reestablishment of a bottomland hardwood forest in the lower Mississippi alluvial valley." Wetlands 22(1): 1-17.

- ↑ Stransky, J.J., J.C. Huntley, and Wanda J. Risner. (1986). Net Community Production Dynamics in the Herb-Shrub Stratum of a Loblolly Pine-Hardwood Forest: Effects of CLearcutting and Site Preparation. Gen. Tech. Rep. SO-61. New Orleans, LA: U.S. Dept of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Forest Experiment Station. 11 p.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 7 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Harrington, T. B., et al. (1998). "Two-year development of southern pine seedlings and associated vegetation following spray-and-burn site preparation with Imazapyr alone or in mixture with other herbicides." New Forests 15: 89-106.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Deyrup, M. J. E., and Beth Norden (2002). "The diversity and floral hosts of bees at the Archbold Biological Station, Florida (Hymenoptera: Apoidea)." Insecta mundi 16(1-3).

- ↑ Miller, Christopher. (2006). Plant Fact Sheet: Eastern Baccharis Baccharis halimifolia. N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture. Somerset, NJ.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Blair, W. F. (1936). "The Florida marsh rabbit." Journal of Mammalogy 17(3): 197-207.

- ↑ Harlow, R. F. (1961). "Fall and winter foods of Florida white-tailed deer." The Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences 24(1): 19-38.

- ↑ Porcher, F. P. (1869). Resources of the southern fields and forests, medical, economical, and agricultural. Richmond, VA, Order of the Surgeon-General.