Asclepias verticillata

| Asclepias verticillata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Gentianales |

| Family: | Asclepiadaceae |

| Genus: | Asclepias |

| Species: | A. verticillata |

| Binomial name | |

| Asclepias verticillata L. | |

| |

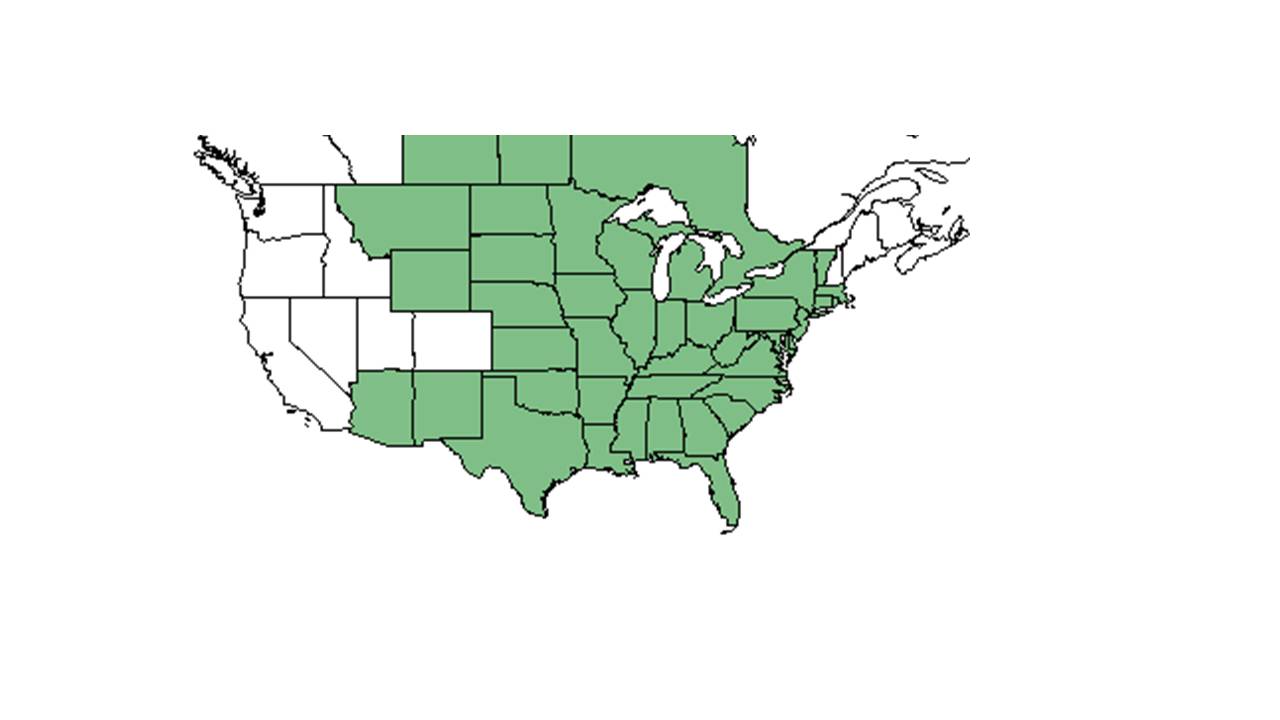

| Natural range of Asclepias verticillata from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Whorled Milkweed

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Asclepias is named for Asklepio, the Greek god of medicine and healing.[1] Verticillata is Latin for whorled.[2]

Synonyms: none.[3]

Varieties: none.[3]

Description

Species in the genus Asclepias are typically perennial herbs with a milky sap. The stems are erect, spreading or decumbent and usually are simple and often solitary. The leaves are opposite to subopposite, are sometimes whorled, and rarely alternate. The corolla lobes are reflexed and are rarely erect or spreading. The filaments are elaborate into five hood forming a corona around the gynosteguim. The corona horns are present in most species.[4]

Specifically, for A. verticillata, the stems are simple or there is branching in the upper third portion. Grows approximately 3-8 dm tall and is pubescent in lines. There are numerous leaves that are whorled or subverticillate, are linear, and grow to be 3-7 cm long and 1-2 mm wide. The leaves are pubescent or glabrate and usually revolute. There are 2-8 umbels coming from the upper nodes, they are 2.2-5 cm broad. The peduncle is 1.5-2.5 cm long. The corolla is greenish white in color. The lobes are 3.5-4.5 mm long and have rose-purple tint at the tip of the lobes. The corona is 3-5 mm in diameter. The acicular horns are exserted. The follicles are erect and are 4.5-8.5 cm long and 4-6 mm broad. Flowers June to September; September to October.[4]

The root system of A. verticillata includes root tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.[5]. Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 29.8 mg/g (ranking 87 out of 100 species studied).[5]

Distribution

It is found from Massachusetts, south to Texas, east to Florida, and west to Arizona.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

Native upland pine and pine-hardwood communities, loblolly pine plantations (Ultisols), borders of wetland depressions within pine communities, sandhills and sand ridges, (Entisols), open calcareous glades, bluffs along Apalachicola River,[6] and roadsides.[7] It can be found in bluestem prairie. It increases with spring burning. It is a warm-season grass.[8] Can occur in areas with soil disturbance.[6] Thrives in frequently burned areas and flowers within two months of burning in the growing season (Robertson observation). Tolerates full sunlight to partial shade. Tolerates moist to xeric conditions but seems to be limited to sandy or calcareous soil. Found barrens of thin soils of rock outcrops (mafic rocks), also in woodlands and sandhills.[3] and in flatwoods.[9] A. verticillata has also been observed on abandoned gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) mounds.[10]

Associated species include Pinus palustris, Quercus laevis, Q. margaretta, Q. rubra, Tragia, Setaria, Panicum, Hedyotis, Euphorbia floridana, Gaillardia aestivalis, Rhynchospora globularis, Pteridium aquilinum, Polianthes, Fraxinus, Melanthera nivea, sweetgum, poison oak, mockernut hickory, and others.[6]

Asclepias verticillata is an indicator species for the North Florida Subxeric Sandhills community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[11]

Phenology

It has been observed to flower from April to September with peak inflorescence in August, and fruit for the same time period.[12][6] It resprouts and flowers within a few weeks of being burned from early spring through summer, but it also flowers in years when it is not burned up to at least five years following fire, primarily in July and August in northern Florida and southern Georgia (KMR[13]). It is one of the last milkweed species to flower and is a common late season host plant for monarch larvae.[14]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind.[15] Asclepias verticillata has seed pods that extend vertically from meristems near the top of the stem. Seeds are dispersed by wind after pod dehiscence. Seeds are up to 4 mm in diameter but have a large white coma facilitating distant seed dispersal (KMR[16]).

Seed bank and germination

If seeds are planted in the fall, seedlings will germinate immediately, yet most likely not to flower until the second year.[17]

Fire ecology

A. verticillata has been found to increase in frequency particularly with annual burns.[18] It has been observed in recently burned mesic Pinus densa (rockland pine) communities of Hendry County, FL.[19] As well, a study found A. verticillata increased with spring burning.[20]

Pollination

Pollination of Asclepias is unusual. Pollen is contained in sacs (pollinia) located in the slits of the flower (stigmatic slits), when a pollinator walks across the flower head, these sacs attach to the pollinator and disperses on to another plant when the pollinator lands and walks.[1] An unpollinated flower can last 4-5 days and produce nectar throughout. A study found that nectar production predominantly occurs daily from 6:00 PM to 10:00 PM, with the most sugar available at night and early morning.[21] There is no specialist insect pollinator[22] Pollinated by Monarch butterflies.

The following species have been observed pollinating A. verticillata: honeybees, bumblebees, Halictid bees (Augochlorella spp., Halictus spp., Lasioglossum spp.), Halictid cuckoo bees (Sphecodes spp.), sand-loving wasps (Tachytes spp.), weevil wasps (Cerceris spp.), Sphecid wasps (Sphex spp., Prionyx spp.), five-banded Tiphiid wasp (Myzinum quinquecinctum), northern paper wasp (Polites fuscatus), spider wasps (Anoplius spp.), Eumenine wasps (Euodynerus spp., etc.), Syrphid flies, thick-headed flies (Physocephala spp., etc.), Tachinid flies, flesh flies (Sarcophagidae), Muscid flies, painted lady (Vanessa cardui) and other butterflies, Peck's skipper (Polites peckius) and other skippers, squash vine borer moth (Melittia cucurbitae) and other moths, and the Pennsylvania soldier beetle (Chauliognathus pennsylvanicus).[23][24][25] Some visitors to A. verticillata have been found to be frequent thieves, meaning they visit the flower, remove the nectar, but do not carry any pollinia. But overall, the wide variety of pollinators suggests that the species is not closely adapted to any certain group of pollinators, but is generally adapted to a wide array of possible pollinators.[21]

Use by animals

It is highly toxic to livestock and horses.[2] However, it is a species of special value for native bees, bumble bees, and honey bees, and supports conservation biological control through attracting predatory or parasitoid insects that prey on pest considered insects.[17] Insects that destructively feed on the foliage, flowers, and seedpods include: small milkweed bug (Lygaeus kalmii), milkweed leaf beetle (Labidomera clivicollis), yellow milkweed aphid (Aphis nerii), and a moth, the delicate Cycnia (Cycnia tenera).[23] Like other milkweeds, A. verticillata is a larval host for Monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus).[17] For humans, it has been used in the past as a domestic remedy for snakebites. The fibre can also be drawn from the plant to be used as sewing thread without the need for further preparation.[26]

Conservation and management

A. verticillata is listed as threatened by the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, and listed as a species of special concern by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management. It can also be considered a weedy or invasive species in some cases due to its toxicity to livestock.[27][17]

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 [[1]]Florida Native Plant Society. Accessed: March 30, 2016

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 [[2]]North Creek Nurseries. Accessed: March 31, 2016

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "weakley" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 4.0 4.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 848-850. Print.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: July 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Guy Anglin, Gary R. Knight, John B. Nelson, Robert L. Lazor, Robert K. Godfrey, R. Kral, R. R. Smith, T. Myint, N. C. Henderson, S. W. Leonard, Cecil R Slaughter, Jimmy Meeks, Brenda Herring, Don Herring, William Lindsey, S.C. Hood, Richard S. Mitchell, Kevin Oakes, Tom Hyde, R.A. Norris, Andre F. Clewell, R. Komarek, R. F. Doren, Chris Cooksey, M. Davis, MacClendons, G. Wilder. States and Counties: Florida: Leon, Lee, Walton, Washington , Okaloosa, Jackson, Gadsden, Jefferson, Pasco, Liberty, Taylor, Marion, Charlotte, Wakulla, Suwannee, Orange, Levy, Citrus, Escambia, Dixie, Georiga: Thomas. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ Observation by Floyd Griffith near Ponce DeLeon Springs State Park, FL, August 23, 2015, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group August 23, 2015.

- ↑ Hover, E. I. and T. B. Bragg (1981). "Effect of season of burning and mowing on an eastern Nebraska Stipa-Andropogon prairie." American Midland Naturalist 105: 13-18.

- ↑ Wunderlin, Richard P. and Bruce F. Hansen. Guide to the Vascular Plants of Florida. Third edition. 2011. University Press of Florida: Gainesville/Tallahassee/Tampa/Boca Raton/Pensacola/Orlando/Miami/Jacksonville/Ft. Myers. 271. Print.

- ↑ Kaczor, S. A. and D. C. Hartnett (1990). "Gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) effects on soils and vegetation in a Florida sandhill." American Midland Naturalist 123: 100-111.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 22 MAR 2019

- ↑ KMR observations at Pebble Hill Plantation Fire Plots near Thomasville, GA.

- ↑ [[3]]Monarch Watch. Accessed: March 31, 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Observations at Pebble Hill Plantation near Thomsville, Georgia

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 [[4]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: March 22, 2019

- ↑ Bragg, T. B., et al. (2001). Preserving restored tallgrass prairie using seasonal burning and mowing: results from 1981-1993 [abstract]. Abstracts from The Ecological Society of America 86th Annual Meeting, Madison, WI.

- ↑ Observation posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group.

- ↑ Hover, E. I. and T. B. Bragg (1981). "Effect of season of burning and mowing on an eastern Nebraska Stipa-Andropogon prairie." American Midland Naturalist 105: 13-18.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Willson, M. F., et al. (1979). "Nectar Production and Flower Visitors of Asclepias verticillata." The American Midland Naturalist 102(1): 23-35.

- ↑ [[5]]Xerces Society. Accessed: March 30, 2016

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 [[6]]Illinois Wildflowers. Accessed: March 31, 2016

- ↑ Grundel, R., et al. (2011). "A survey of bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of the Indiana Dunes and Northwest Indiana, USA." Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 84(2): 105-138.

- ↑ Tooker, J. F., et al. (2006). "Floral host plants of Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) of central Illinois." Annals of the Entomological Society of America 99(1): 96-112.

- ↑ Porcher, F. P. (1869). Resources of the southern fields and forests, medical, economical, and agricultural. Richmond, VA, Order of the Surgeon-General.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 22 March 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.