Aristida purpurascens

| Aristida purpurascens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Cyperales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Genus: | Aristida |

| Species: | A. purpurascens |

| Binomial name | |

| Aristida purpurascens Poiret | |

| |

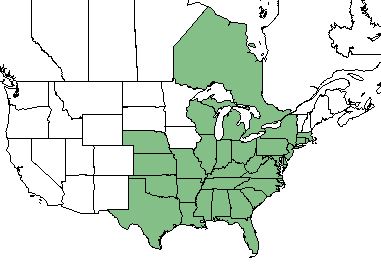

| Natural range of Aristida purpurascens from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common Name(s): arrowfeather,[1] arrowfeather threeawn[2]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Varieties: A. purpurascens var. purpurascens; A. purpurascens var. tenuispica; A. purpurascens var. virgata[2], A. purpurascens var. minor Vasey

Description

A. purpurascens is a monoecious perennial graminoid[2] that tolerates moderate shade.[3] In sandhill pine communities, it can be found in a green or strongly glaucous-blue form.[1] It reaches heights of 1.5-2.0 ft (0.46-0.61 m) with flat narrow leaf blades 4-12 in (10.2-30.5 m) long. Seedheads have a narrow panicle that is 1/3 to 1/2 the height of the plant.[3] Awnes are 1/2 to 3/4 inches long[3] and twice as thick at the base[4]. Seeds contain barblike hairs at the base.[3]

Distribution

Aristida purpurascens is found from Massachusetts west to Wisconsin and Kansas and southward to Florida and Texas.[1][2] It may also be found in parts of Nebraska and Ontario, Canada.[2][5]

Ecology

Habitat

This species is found in dry habitats[1] including pine savannas, fields, and waste places,[4][6] especially those containing sandy or rocky soils.[1] A study in Michigan old fields showed A. purpurascens had the second highest standing crop, which peaked in August at 270 g m-2 dry weight.[7] In Maryland pine-cedar savannas, A. purpurascens was the second most important species (IV = 23.5%; Importance Value Index[IV] - calculated by summing the relative frequency and relative cover).[8] Lesser importance was found in Maryland serpentine barrens between 1989 and 1992 (IV = 1.4-6.5%).[9] Despite its importance in dryer systems, A. purpurascens is also observed in seepage bogs with similar, or slightly greater, coverage as pine savannas.[6] In Louisiana sandstone outcrops where A. purpurascens also occurs, topsoil calcium were measured at 2267.5 ppm and magnesium at 586.5 ppm.[10] Dead material of A. purpurascens disappears from 2.0-2.7 mg g-1 in the fall (mid July-mid November) and 0.1-1.0 mg g-1 the rest of the year in a Michigan old field.[7]

Phenology

Seeds production usually peaks in June.[3]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity. [11]

Fire ecology

A. purpurascens withstands annual burning.[3] On Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, May and July burns increased the percentage of flowering culms on A. purpurascens.[12] In Maryland serpentine barrens, clearing and the combination of clearing and burning increased the importance value percentage to between 3.0-12.2% from between 1.4-6.5%[9]

Use by animals

Seeds from this grass compose 2-5% of the diet of some terrestrial birds.[2] A study in Michigan showed the seeds of A. purpurascens was also abundant in the caches of prairie deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus bairdii).[13] For a few weeks in the spring cattle can graze arrowfeather, but in the rest of the year it is considered a low quality forage.[3]

Conservation and Management

To reduce the abundance of A. purpurascens, grazing can be allowed for 2-3 weeks in the spring just before seedheads appear.[3]

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley A. S.(2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 14 December 2017). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Magee P. (2012). Plant fact sheet: Arrowfeather threeawn Aristida purpurascens. United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Baton Rouge, LA.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Allred K. W. (1986). Studies in the Aristida (Gramineae) of the southeastern United States. IV. Key and Conspectus. Rhodora 88(855):367-387.

- ↑ Catling P. M., Reznicek A. A., Riley J. L. (1977). Some new and interesting grass records from southern Ontario. Canadian Field-Naturalist 91(4):350-359.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Drewa P. B., Platt W. J., and Moser B. (2002). Community structure along elevation gradients in headwater regions of longleaf pine savannas. Plant Ecology 160:61-78.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Wiegert R. G. and Evans F. C. (1964). Primary production and the disappearance of dead vegetation on an old field in southeastern Michigan. Ecology 45(1):49-63.

- ↑ Tyndall R. W. and Farr P. M. (1989). Vegetation structure and flora of a serpentine pin-cedar savanna in Maryland. Castanea 54(3):191-199.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Tyndall R. W. (1994). Conifer clearing and prescribed burning effects to herbaceous layer vegetation on a Maryland serpentine "barren." Castanea 59(3):255-273.

- ↑ Kley J. E. V. (1999). The vegetation of the Kisatchie Sandstone Hills, Louisiana. Castanea 64(1):64-80.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Shepherd B. J., Miller D. L., and Thetford M. (2012). Fire season effects on flowering characteristics and germination of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) savanna grasses. Restoration Ecology 20(2):268-276.

- ↑ Howard W. E. and Evans F. C. (1961). Seeds stored by prairie deer mice. Journal of Mammalogy 42(2):260-263.