Hieracium gronovii

| Hieracium gronovii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo was taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Hieracium |

| Species: | H. gronovii |

| Binomial name | |

| Hieracium gronovii L. | |

| |

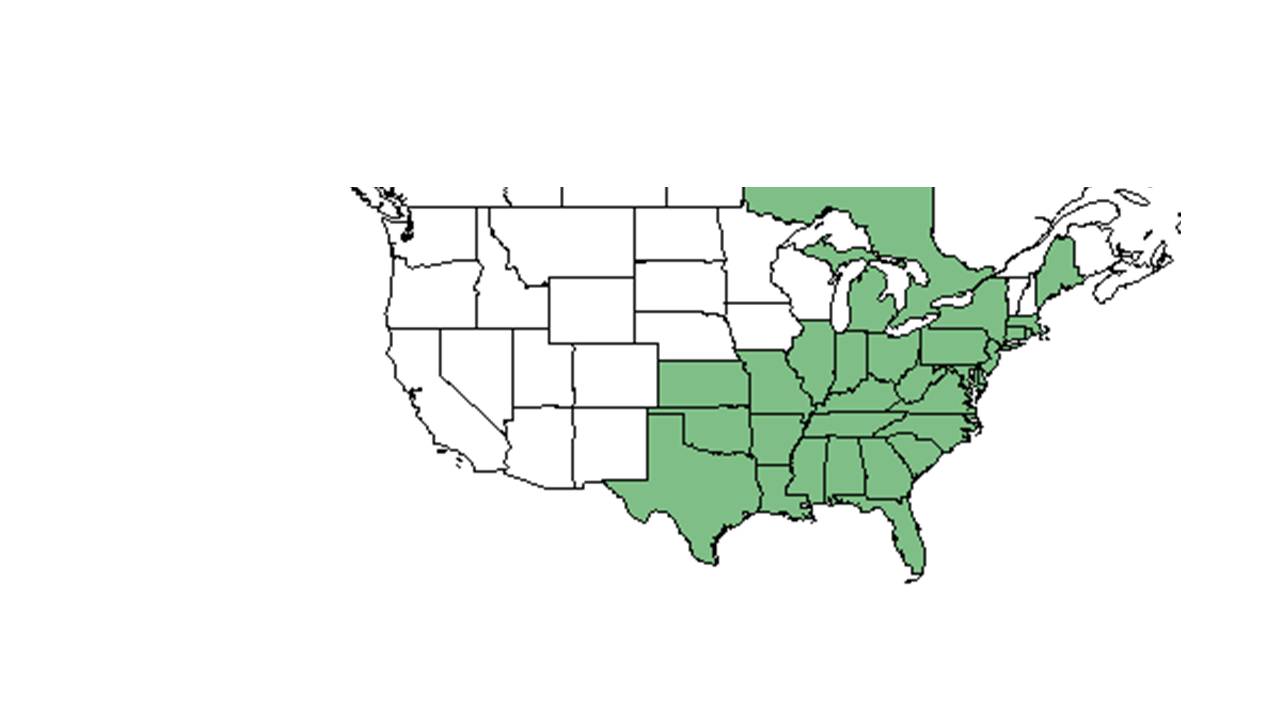

| Natural range of Hieracium gronovii from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: queendevil; beaked hawkweed

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

A description of Hieracium gronovii is provided in The Flora of North America. Hieracium gronovii is a perennial herbaceous species.

Distribution

Hieracium gronovii is distributed from Massachusetts west to Michigan and Kansas south to central peninsular Florida and Texas.[1] It is also native to the Canadian province of Ontario.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

Generally, H. gronovii can be found in dry forests, sandhills, roadsides, and various woodland margins.[1] It occurs in moist or dry sandy soils, from dry loamy sand to moist sandy peat, dry sand, and moist sandy loam. This species can occur in a range of native and disturbed habitats. Native habitat includes mixed oak-pine sandhills, pine-scrub oak-palmetto communities, longleaf pine savannas, turkey oak barrens, open mixed hardwood forests, and sandy areas bordering cypress ponds and hillside bogs. However, it can also be found in disturbed areas including roadsides, old fields, open annually mowed pineland, power line corridors, and drainage ditches.[3] Additionally, H. gronovii is frequent and abundant in the North Florida Subxeric Sandhills and Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[4]

This species was shown to decrease in frequency in response to the control of woody species.[5] H. gronovii has shown regrowth in reestablished longleaf pine woodlands that were disturbed by agriculture in South Carolina coastal plain communities, making it an indicator species for post-agricultural woodlands.[6] H. gronovii was found to be an increaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[7]

Associated species include Quercus margaretta, Pinus palustris, Aristida stricta, Serenoa repens, Crotalaria spectabilis, Lechea mucronata, Desmodium tortuosum, Rubus cuneifolius, Heterotheca subaxillaris, Andropogon virginicus, Paspalum notatum, Solidago altissima, and Eupatorium compositifolium.[3]

Phenology

This species generally flowers from July until November.[1] H. gronovii has been observed flowering in January, February, and July through November, and fruiting in May. [3][8]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind. [9]

Seed bank and germination

Several short-lived perennial forbs also have a seed bank persistent for at least several years.[10] It has been seen to germinate from the seed bank at early successional 1 and 2 year old field sites.[11] As well, fire disturbance has been shown to positively affect seed germination over time.[12]

Fire ecology

Hieracium gronovii has been found in habitats maintained by frequent fire[3] such as the Pebble Hill plantation in north Florida[13] where populations persist through repeated annual burns.[14] Overall, it significantly increases in frequency in response to fire disturbance.[15] This species has been shown to benefit most from summer burn regiments rather than winter or spring burn regiments.[16] As well, it is most frequent in low fire return intervals.[17] Fire disturbance has also been shown to increase the amount of seed germination over a 1 year time span.[12]

Pollination

Hieracium gronovii has been observed at the Archbold Biological Station to host leafcutting bees such as Anthidiellum perplexum (family Megachilidae), as well as sweat bees from the family Halictidae such as Augochloropsis sumptuosa, Halictus poeyi, and Lasioglossum coreopsis.[18] Other pollinators of Hieracium gronovii in the Hymenoptera order include Dialictus coreopsis, Halictus ligatus, Anthidium maculifrons, Megachile breuis pseudobrevis, and M. georgica, M. mendica, Ceratina dupla, C. mikmaqi, Augochlora pura, Augochlorella aurata, Agapostemon splendens, Lasioglossum bruneri, L. macoupinense, L. pectorale, L. pilosum, and Heriades variolosus.[19][20]

Herbivory and toxicology

Additionally, this species has been observed to host aphids from the Uroleucon sp. (family Aphididae).[21] H. gronovii is known to be eaten by white-tailed deer.[22]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Hieracium gronovii is listed as possible extirpated by the Maine Department of Conservation, Natural Areas Program. As well, the genus Hieracium is listed as a class C noxious weed for non-native species by the state of Washington.[2] It is also imperiled in Kansas and Ontario.[23]

Cultural use

Medicinally, leaves of H. aculeatus can be bruised and then applied to warts to help eradicate them.[24]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 22 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Wilson Baker, Robert Blaisdell, Chris Cooksey, George R. Cooley, R. A. Davidson, Richard J. Eaton, J. P. Gillespie, Robert K. Godfrey, S. R. Hill, Richard D. Houk, Ed Keppner, Lisa Keppner, Gary R. Knight, R. Komarek, R. Kral, Robert L. Lazor, Sidney McDaniel, Richard S. Mitchell, John Morrill John B. Nelson, R. A. Norris, R. E. Perdue Jr., James D. Ray Jr., Paul L. Redfearn Jr., Cecil R. Slaughter, Bian Tan, R. F. Thorne, and Jean W. Wooten. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Bay, Calhoun, Clay, Columbia, Dade, Franklin, Gulf, Hernando, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Nassau, Okaloosa, Osceola, Putnam, Santa Rosa, Taylor, and Wakulla. Georgia: Grady and Thomas.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Harrington, T. B. (2011). "Overstory and understory relationships in longleaf pine plantations 14 years after thinning and woody control." Canadian Journal of Forest Research 41: 2301-2314.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Platt, W. J., S. M. Carr, et al. (2006). "Pine savanna overstorey influences on ground-cover biodiversity." Applied Vegetation Science 9: 37-50.

- ↑ Oosting, H. J. and M. E. Humphreys (1940). "Buried viable seeds in a successional series of old field and forest soils." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 67(4): 253-273.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Parks, G. R. (2007). Longleaf pine sandhill seed banks and seedling emergence in relation to time since fire, University of Florida. Master of Science: 84.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Taft, J. B. (2003). "Fire effects on community structure, composition, and diversity in a dry sandstone barrens." Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 130: 170-192.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ Mehlman, D. W. (1992). "Effects of fire on plant community composition of North Florida second growth pineland." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 119(4): 376-383.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Deyrup, M. J. E., and Beth Norden (2002). "The diversity and floral hosts of bees at the Archbold Biological Station, Florida (Hymenoptera: Apoidea)." Insecta mundi 16(1-3).

- ↑ Grundel, R., et al. (2011). "A survey of bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of the Indiana Dunes and Northwest Indiana, USA." Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 84(2): 105-138.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Atwood, E. L. (1941). "White-tailed deer foods of the United States." The Journal of Wildlife Management 5(3): 314-332.

- ↑ [[2]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: May 22, 2019

- ↑ Porcher, F. P. (1869). Resources of the southern fields and forests, medical, economical, and agricultural. Richmond, VA, Order of the Surgeon-General.