Dichanthelium aciculare

| Dichanthelium aciculare | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida – Monocotyledons |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae ⁄ Gramineae |

| Genus: | Dichanthelium |

| Species: | D. aciculare |

| Binomial name | |

| Dichanthelium aciculare (Desv. ex Poir.) Gould & C.A. Clark | |

| |

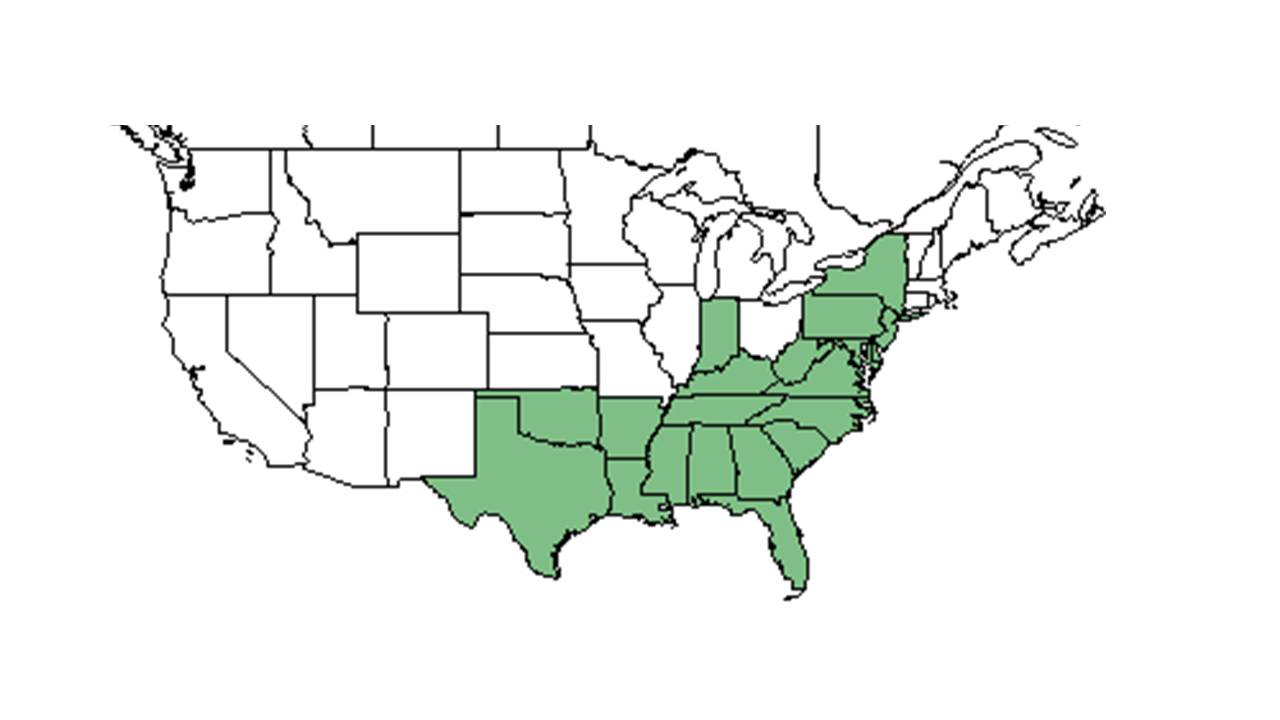

| Natural range of Dichanthelium aciculare from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: needleleaf rosette grass; needle-leaf witchgrass

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Dichanthelium aciculare (Desvaux ex Poiret) Gould & Clark ssp. aciculare; Panicum aciculare Desvaux ex Poiret[1]

Varieties: Panicum aciculare; P. arenicola W.W. Ashe; P. bennettense M.V. Brown[1]

Description

Generally, for the Dichanthelium genus, they have "spikelets usually in panicles, round or nearly so in cross section, 2-flowered, terminal fertile, basal sterile, neutral or staminate. First glume usually present, 2nd glume and sterile lemma similar; fertile lemma and palea indurate without hyaline margins. Taxonomically our most difficult and least understood genus of grasses, more than 100 species an varieties are ascribed to the Carolinas by some authors. Note general descriptions for species groups (e.g., 1-4, 5-8, 9-13, and 26-62)." [2]

Specifically, for the D. aciculare species they are "perennial with distinct basal rosettes; branching, when present, from nodes above basal rosette. Leaves basal and cauline, vernal and autumnal. Culms 1.5-6 dm tall, nodes bearded internodes long pilose. Blades to 8 cm long, lower blades 1-6 mm wide, uppermost less than 2 mm wide, glabrous or pilose on both surfaces, margins glabrous, usually long ciliate basally; sheaths pilose or puberulent; ligules ciliate, 1-3 mm long. Autumnal blades involute, 0.5-2 mm wide, glabrous to sparsely pilose on both surfaces. Panicle exserted, 2-7 cm long, 1-5 cm broad; rachis glabrous or puberulent, branches spreading-ascending, scaberulous, occasionally pilose basally. Spikelets obovoid, 1.5-2 mm long; pedicels scaberulous. First glume glabrous, scarious, acute, 0.6-0.8 mm long, 2nd glume and sterile lemma pubescent or puberulent, obtuse, 1.6-2 mm long; fertile lemma and palea 1.5-1.8 mm long, nerveless or faintly nerved, yellowish or brownish at maturity, lustrous, acute, or obtuse. Grain 1 mm long, yellowish or purplish, broadly ellipsoid or subglobose."[2]

Distribution

D. aciculare can be found in the United States from New Jersey down to north Florida and west to Texas and Oklahoma. It is also native to the West Indies and northern portions of South America[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Dichanthelium aciculare can generally be found in sandy woods and fields.[1] Other habitats it has been observed in include wet pine flatwoods, dune swales, bayheads, Myrica flats, turkey oak barrens, longleaf pine/turkey oak woods, creek banks, flooded cattail sloughs, depression marshes, coastal hammocks, longleaf pine/scrub oak ridges, cabbage palm/mixed oak communities, bog margins, sand pine scrubs, open palmetto scrubs, coastal scrubs, and edges of cypress depression swamps. It has also been recorded in disturbed areas such as along highways, man-made ponds, roadsides, and old fields. Soil types include loam, sand, sandy peat, sandy clay, loamy sand, coarse sand, and silt.[3]

D. aciculare was found to be an increaser in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances but neutral in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[4]

Associated species include Pinus palustrus, Quercus laevis, Aristida beyrichiana, Baccharis and Myrica.[3]

Phenology

General flowering time is between May and October.[1] This species has been observed to flower in April and May, July, and September and October with peak inflorescence in April and May.[5][3] Fruiting has been observed in May.[3]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by ants and/or explosive dehiscence. [6]

Seed bank and germination

Seeds of D. aciculare were found to persist in the seed bank after a fire disturbance.[7] Another study found them to persist up to even 35 years with fire disturbance.[8]

Fire ecology

Populations of Dichanthelium aciculare have been known to persist through repeated annual burns,[9][10] and has been observed in recently burned mesic pine flatwoods and a frequently burned low hillside seepage slope.[3]

Herbivory and toxicology

D. aciculare consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet for large mammals and about 10-25% of the diet for terrestrial birds.[11]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

This species is listed as endangered by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and Energy and by the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation.[12]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 142-152. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: October 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Tara Baridi, H.L. Blomquist, Edwin L. Bridges, W.C. Brumbach, R.B. Channel, A.F. Clewell, Richard R. Clinebell II, R.A. Davidson, Delzie Demaree, Rex Ellis, R.K. Godfrey, Ann F. Johnson, R. Kral, Sidney McDaniel, R. A. Norris, Steve L. Orzell, A.E. Radford, H.R. Reed, Lloyd H. Shinners, Cecil R. Slaughter, John W. Thieret, R.F. Thorne, West, Ben Wheeler. States and Counties: Alabama: Covington, Houston. Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Clay, Duval, Escambia, Franklin, Lee, Leon, Liberty, Madison, Polk, Putnam, Volusia, Wakulla, Washington. Georgia: Baker, Grady, McIntosh, Mitchell,Thomas. Louisiana: Jackson, Ouachita, Vernon. Mississippi: Harrison, Jackson, Lauderdale,Pearl River. North Carolina: Craven, Durham. South Carolina: Clarendon, Edgefield. Texas: Freestone, Van Zandt. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 26 APR 2019

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Kalmbacher, R., et al. (2005). "Seeds obtained by vacuuming the soil surface after fire compared with soil seedbank in a flatwoods plant community." Native Plants Journal 6: 233-241.

- ↑ Parks, G. R. (2007). Longleaf pine sandhill seed banks and seedling emergence in relation to time since fire, University of Florida. Master of Science: 84.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 26 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.