Eryngium yuccifolium

Common name: button eryngo [1], moccasin-master [2], southern/northern rattlesnake master [2]

| Eryngium yuccifolium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John B. of Blue Moon | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Apiales |

| Family: | Apiaceae |

| Genus: | Eryngium |

| Species: | E. yuccifolium |

| Binomial name | |

| Eryngium yuccifolium Michx. | |

| |

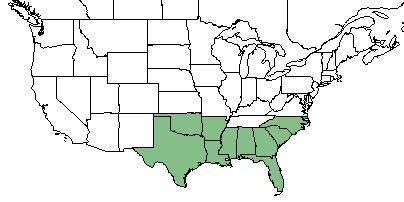

| Natural range of Eryngium yuccifolium from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Eryngium synchaetum (A. Gray ex J.M. Coult. & Rose) J.M. Coult. & Rose; Eryngium aquaticum Linnaeus.[3]

Varieties: Eryngium yuccifolium Michaux var. synchaetum A. Gray ex Coulter & Rose; Eryngium yuccifolium Michaux var. yuccifolium.[3]

The genus name Eryngium is Greek for "prickly plant", and the specific epithet yuccifolium is Greek for "yucca leaves".[4]

Description

E. yuccifolium is a perennial forb/herb of the Apiaceae family native to North America. [1] It has grasslike parallel-veined leaves with a stout furrowed stem and the flowers borne in a dense, stout-stemmed head. [5] Reaches heights between 2 to 6 feet with a short and thick rootstock. Basal leaves are bluish green in color, thick and parallel veined, with weak or soft prickles along the edges that are spaced apart. Flower heads arranged on stout peduncles at the tip of each stem, each spherical and with whitish bracts that sharply stick out from the flower inflorescence. These heads have a honey-like odor.[4]

Distribution

E. yuccifolium can be found along the southeastern coast of the United States from Texas to North Carolina.[1] E. yuccifolium var. synchaetum is a southeastern coastal plain endemic, ranging from southeast North Carolina to southern Florida and west across the coastal plain: the exact limits of its range is obscure. E. yuccifolium var. yuccifolium is distributed througout midwestern and southeastern North America; the exact limits of this variety are obscure, but most likely from New Jersey, Ohio, southern Michigan, Wisconsin, Maine, and Nebraska south to the panhandle of Florida and Alabama, Mississippi, northern Louisiana, and eastern Texas.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

E. yuccifolium var. synchaetum is found in wet savannas, especially those over calcareous clay soils, and E. yuccifolium var. yuccifolium can be found in olivine barrens, diabase glades and barrens, prairies, pine flatwoods on clay or loamy soils, pine savannas, and other open areas with some periodic moisture, generally in places that show some prairie affinities.[2] Specimens have been collected from pine woods, prairie, sandy woodland, sandy savanna, stream bottomland with peat-loam muck, open wiregrass longleaf pine flatwoods, river banks, palmetto flatwoods, marshes, and hammocks.[6] This species is overall best suited to calcareous soils.[7]

Associated species include Crataegus sp., Hypericum sp., Polygala sp., Phoebanthus sp., Balduina sp., Bigelowia sp., Cyperus sp., Styrax americana, Saururus cernuus, Crinum americanum, Cicuta mexicana, and Hymenocallis sp.[6]

Phenology

Generally, this species flowers from June until August.[2] E. yuccifolium has been observed flowering April through August and November. [8] It has been observed fruiting in August and September.[6]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind.[9]

Fire ecology

The spread of E. yuccifolium is highly favored by fire. It has been shown to increase establishment of seedlings as an effect of fire.[10] It has also been shown to overall increase in abundance in response to fire disturbance.[11] Specifically, E. yuccifolium will flower roughly 80 days after a burn and it will mature and fruit about 130 days after a burn. [12] It seems to benefit from spring and summer burn regiments rather than winter burn regiments.[13]

Pollination and use by animals

E. yuccifolium is mostly self-pollinated.[4] However, it is also recognized by pollination ecologists to be of special value to native bees since it attracts large numbers for pollination.[14] It has been observed that E. yuccifolium is pollinated by members of the Hymenoptera order, such as Apis mellifera, Bombus impatiens, Hylaeus modestus, Agapostemon splendens, Lasioglossum imitatum, Lasioglossum vierecki, Megachile petulans, and Megachile mendica.[15] Flies of the families Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) have been collected from the flowers of this plant as well and are thought to pollinate.[16] Additionally, E. yuccifolium has been observed to host sweat bees such as Lasioglossum imitatum (family Halictidae) and assassin bugs such as Zelus cervicalis (family Reduviidae).[17]

E. yuccifolium is unpalatable to grazing livestock due to its spiny leaves and flowers that also make walking through clumps of this plant difficult. This species also supports conservation biological control through attracting predatory or parasitoid insects that in turn prey upon pest insects.[14]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

E. yuccifolium is listed as endangered/extirpated by the Maryland Natural Heritage Program Department of Natural Resources, and as threatened by the Michigan Natural Features Inventory Department of Natural Resources and by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources Division of Natural Areas and Preserves. [1] For management, weed competition can be reduced by either using approved herbicides or by mowing the area. Fire disturbance can also be used when plant vigor decreases or when invading species threaten natural stands.[4]

E. yuccifolium can be commonly used in prairie restoration projects to help restore overall groundcover biodiversity.[4]

Cultural use

Historically, the roots of this plant have been used to treat liver problems rheumatism, respiratory problems, induce vomiting, and treat rattlesnake bites. An infusion was drank to relieve muscle pains and bladder problems.[18]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 USDA Plant Database https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=ERYUS

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Henry, J. and S. Bruckerhoff. (2006). Plant Fact Sheet: Rattlesnake Master Eryngium yuccifolium. N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture. Elsberry Plant Materials Center, Elsberry, MO.

- ↑ Sievers, A. F. (1930). American medicinal plants of commercial importance. Washington, USDA.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Delzie Demaree, R.Kral, Fred Barkley, H.F. L. Rock, R.L. Wilbur, Harry Ahles, P.L. Redfearn, S.B. Jones, John Thieret, E.J. Palmer, F.S. Earle, C.F. Baker, Raymond Athey, R.K. Godfrey, Roomie Wilson, Norlan Henderson, Gwynn Ramsey, H. Larry Stripling, John Bernard, Samuel B, Jones Jr., A.F. Clewell, Robert Lazor, M. Davis, R. Komarek, Cecil Slaughter, Richard Mitchell, Sydney Thompson, Culver Gidden, Annie Schmidt, W.P. Adams, Marc Minno, J.B. Nelson, R.H. Wnek, Gary Knight, Paul Fortsch, Nancy Edmonson, R.A. Pursell, Jean Wooten, S.W> Leonard, Angus Gholson, A.E. Radford, David Webb, Leon Bates, J. Haesloop, James W. Hardin, Wilbur Duncan, D.S. Correll, Helen Correll, Robert Thorne. States and counties: Florida (Wakulla, Gadsden, Franklin, Jefferson, Levy, Jackson, Gadsden, Leon, Washington, Santa Rosa, Okaloosa, Bay, Washington, Taylor, Sarasota, Calhoun, Dixie, Liberty, Brevard, Charlottee, indian River, Sumter, Palm Beach, Hernando) Mississippi (Jackson, Lamar, Covington, George) Georgia (baker, Lee, Seminole, Ben Hill, Cook, Johnson, Thomas, Grady, Charlton, Lowndes) Illinois (Cook, Champaign) Alabama (Conecuh, Colbert, Houston, Lee, Geneva) Texas (Bastrop) North Carolina (Pender, Cherokee) Tennessee (Coffee) Kentucky (Lyon, Todd) Louisiana (Tangipahoa, St. Tammany, Vernon, Lafayette) Missouri (Bates, Jasper, Greene) Arkansas (Lawrence)

- ↑ Van Kley, J. E. (1999). "The Vegetation of the Kisatchie Sandstone Hills, Louisiana." Castanea 64(1): 64-80.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 21 MAY 2018

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Curtis, J. T. and M. L. Partch (1948). "Effect of fire on the competition between blue grass and certain prairie plants." American Midland Naturalist 39: 437-443.

- ↑ Moore, W. H., et al. (1982). "Vegetative response to prescribed fire in a north Florida flatwoods forest." Journal of Range Management 35: 386-389.

- ↑ Comment by Jimi Cheak on Reed Noss post in January 26, 2018, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 10, 2019

- ↑ Grundel, R., et al. (2011). "A survey of bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of the Indiana Dunes and Northwest Indiana, USA." Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 84(2): 105-138.

- ↑ Tooker, J. F., et al. (2006). "Floral host plants of Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) of central Illinois." Annals of the Entomological Society of America 99(1): 96-112.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.