Gordonia lasianthus

| Gordonia lasianthus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Theales |

| Family: | Theaceae |

| Genus: | Gordonia |

| Species: | G. lasianthus |

| Binomial name | |

| Gordonia lasianthus (L.) Ellis | |

| |

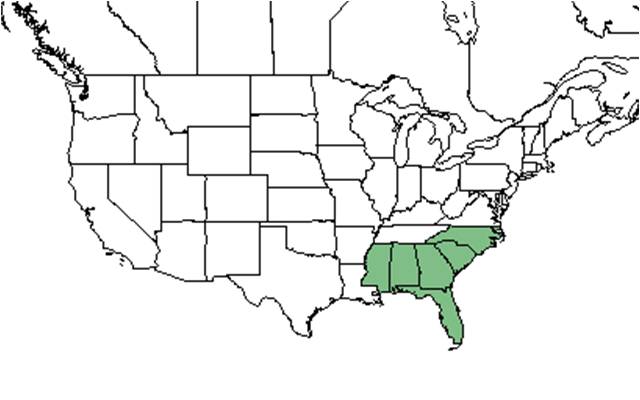

| Natural range of Gordonia lasianthus from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Loblolly bay

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

A description of Gordonia lasianthus is provided in The Flora of North America.

Loblolly bay is a perennial, evergreen tree with large, white, fragrant, cup-shaped flowers. The leaves are leathery, entire, oblong and oblanceolate and will turn scarlet in the fall.[2][3] It often grows with sweet bay, (Magnolia virginiana) and is easily distinguishable by having a light green underside while sweet bay has a white underside.[4]

Distribution

This southeast endemic is found in hydric habitats throughout the Coastal Plain. Its range extends from northeast North Carolina to southern peninsular Florida and west to southern Mississippi.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Gordonia lasianthus has been found along margins of titi swamps, densely wooded hammocks, swampy depressions, cypress domes, an ecotone between a titi-sweet bay swamp and a pond pine flatwood, ravine bottoms, shrub bogs, wet pine flatwoods, mesic steepheads, pocosins, bayheads, and bald cypress/mixed hardwoods swamps. Seedlings have been observed to require significant site disturbance exposing mineral soil, to become established. [5] It has been found to occur in disturbed areas such as cut-over pinewoods and powerline corridors. [6] Grows in acidic, swampy soils, with an accumulation of organic matter. Soil types include Spodosols, Inceptisols, Ultisols, and Histosols[7] and has been observed to grow in loamy sand. [6] Loblolly bay is rarely observed to occur in pure stands (Gresham and Lipscomb 1985), but has been observed to be the dominate canopy in some Carolina bays. [8] G. lasianthus responds positively to soil disturbance by heavy silvilculture in North Carolina.[9] However, it does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[10]

Associated species include Stewartia, Illicium, Ilex opaca, Ilex glabra, Persea borbonia, Magnolia glauca, Rhus vernix, Clethra, Cliftonia, Nyssa sylvatica, Cyrilla racemiflora, Pinus elliottii, Quercus nigra, Liquidambar, Magnolia virginiana, Oxydendron, Illicium floridanum, Myrica cerifera, Liriodendron, Pickneya, Rhododendron viscosum, Lyonia lucida, Serenoa, Osmunda, Sphagnum, and Lycopodium. [6]

Gordonia lasianthus is an indicator species for the North Florida Wet Flatwoods community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[11]

Phenology

The large, white fragrant flowers can be found flowering May through August with peak inflorescence in June and July.[6] The fruit is a hard, woody, five-valved capsule about 0.6 inches long; four to eight flat, winged seeds can be found in each valve.[6][12]

Seed dispersal

The majority of seeds fall with in a radius three times the height of the parent tree. Wind shakes the seeds out of the capsules; and the empty capsules will remain attached to the parent tree until peduncle and capsule abscission.[7]

Seed bank and germination

Germination of loblolly bay is epigeal and most seedlings do not live past the first growing season.[7]

Fire ecology

Gordonia lasianthus usually occurs in areas that do not experience a lot of fire, such as bayheads . Swamps dominated by pondcypress can develop into bays dominated by G. lasianthus when fire is suppressed and there is an accumulation of organic matter. Organic matter accumulates in unburned areas, providing a desirable habitat for G. lasianthus to germinate and grow. [13]

Following a disturbance, such as fire, G. lasianthus is a sprouter, recovering vegetatively from roots or stems. Sprouters invest more energy into below ground structures and produce fewer seeds, and are favored in systems with severe and frequent disturbance. G. lasianthus occurs commonly in bayheads, which have one of the lowest fire frequency of any forested wetland in Florida, but due to the deep organic soil, it can ignite during the dry season. The thin bark of G. lasianthus does not provide much insulation from smoldering heat, causing a low survival rate in bayhead interiors, where there is a lot of smoldering post-fire. G. lasianthus has the highest survival rate near bayhead edges, where char heights are the greatest, causing G. lasianthus to basally resprout. [14] Severe disturbance promotes basal sprouting and mild disturbance promotes sprouting in the tree crown (Bond and Midgley 2001).

Seedlings have been observed in plowed fire lines around a site that received a winter burn, but none were observed within the burned area (Gresham and Lipscomb 1985).

Pollination

Flowers are pollinated by bees, flies and hummingbirds.[7]

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Gordonia lasianthus at Archbold Biological Station: [15]

Sphecidae: Ectemnius rufipes ais

Vespidae: Pachodynerus erynnis, Polistes dorsalis hunteri

Use by animals

Deer eat the foliage.[2]

Diseases and parasites

G. lasianthus, M. virginiana and Persea borbonia can be found growing together in bayheads and Carolina Bays. Laurel wilt disease is a fungal disease transmitted by Xyleborus glabratus, a non-native beetle, that causes Persea borbonia to die. With the death of Persea borbonia there is an increase in open canopy gaps, which G. lasianthus and M. virginiana encroach and cause an alteration of the community composition and structure. More seedlings of G. lasianthus have been observed at these sites, suggesting that it will become the most dominant species over time. [16] It has been observed that G. lasianthus is not effected by laurel wilt disease. [17]

Root rot can be a problem for this species when young.[2]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

Cypert, Eugene. 1973. Plant succession on burned areas in Okefenokee Swamp following the fires of 1954 and 1955. In: Proceedings, annual Tall Timbers fire ecology conference; 1972 June 8-9; Lubbock, TX. Number 12. Tallahassee, FL: Tall Timbers Research Station: 199-217.

George B. Landman, and Eric S. Menges. “Dynamics of Woody Bayhead Invasion into Seasonal Ponds in South Central Florida”.

Castanea 64.2 (1999): 130–137.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 [[1]] Accessed: December 16, 2015

- ↑ [[2]]Accessed: December 16, 2015

- ↑ [[3]]Accessed: December 17, 2015

- ↑ Gresham, Charles A., and Donald J. Lipscomb. “Selected Ecological Characteristics of Gordonia Lasianthus in Coastal South Carolina”. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 112.1 (1985): 53–58.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: October 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Sarah Baxter, James R. Burkhaulter, N.H. Chevalier, Andre F. Clewell, H.S. Conard, H.A. Davis, Wayne R. Faircloth, A. Gholson Jr., R.K. Godfrey, D.W. Hall, Don Harrison, E.A. Hebb, R. Kral, O. Lakela, S.W. Leonard, Hui Lin Li, T. Myint, J.B. Nelson, Jackie Patman, James D. Ray Jr., C. Rhinehart, P.L. Redfearn Jr., Grady W. Reinert, Cecil R. Slaughter, A.G. Shuey, R.R. Smith, E. Tyson, D.B. Ward, Jean W. Wooten. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Baker, Bay, Columbia, DeSoto, Dixie, Escambia, Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Hamilton, Hardee, Highlands, Hillsborough, Jefferson, Lake, Leon, Liberty, Madison, Manatee, Marion, Nassau, Okaloosa, Orange, Polk, Putnam, Seminole, Taylor, Volusia, Wakulla, Walton. Georgia: Clarke, Grady. Pennsylvania: Phillidelphia. South Carolina: Pickens. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 [[4]]Accessed December 15, 2015

- ↑ Dimick, B. P., J. M. Stucky, et al. (2010). "Plant-Soil-Hydrology Relationships in Three Carolina Bays in Bladen County, North Carolina." Castanea 75(4): 407-420.

- ↑ Cohen, S., R. Braham, and F. Sanchez. (2004). Seed Bank Viability in Disturbed Longleaf Pine Sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 DEC 2016

- ↑ Casey, W. P. and K. C. Ewel (2006). "Patterns of succession in forested depressional wetlands in north Florida, USA." Wetlands 26(1): 147-160

- ↑ Matlaga, D. P., P. F. Quintana-Ascencio, et al. (2010). "Fire mediated edge effects in bayhead tree islands." Journal of Vegetation Science 21(1): 190-200.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Spiegel, K. S. and L. M. Leege (2013). "Impacts of laurel wilt disease on redbay (Persea borbonia (L.) Spreng.) population structure and forest communities in the coastal plain of Georgia, USA." Biological Invasions 15(11): 2467-2487.

- ↑ Mayfield, A. E. and J. L. Hanula (2012). "Effect of Tree Species and End Seal on Attractiveness and Utility of Cut Bolts to the Redbay Ambrosia Beetle and Granulate Ambrosia Beetle (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae)." Journal of Economic Entomology 105(2): 461-470.