Vitis rotundifolia

| Vitis rotundifolia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Rhamnales |

| Family: | Vitaceae |

| Genus: | Vitis |

| Species: | V. rotundifolia |

| Binomial name | |

| Vitis rotundifolia Michx. | |

| |

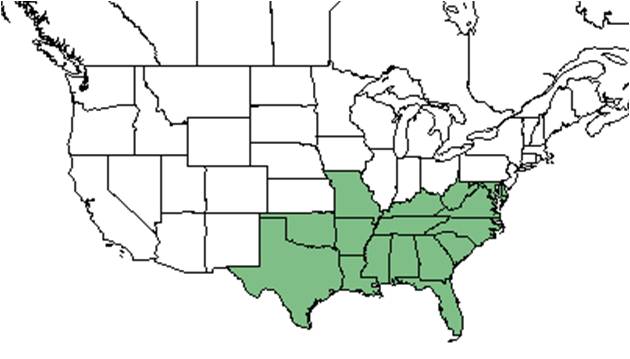

| Natural range of Vitis rotundifolia from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Muscadine

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Muscadinia munsoniana (Simpson ex Munson) Small; Muscadinia rotundifolia (Michaux) Small.[1]

Variations: Vitis rotundifolia var. munsoniana Simpson ex Munson.[2]

Description

"High-climbing or trailing vines; pith brown, continuous or discontinuous through the nodes. Leaves simple, acute or acuminate, serrate, base cordate, petiolate. Inflorescences paniculate. Calyx flat, round, usually without lobes; petals 5, 0.5-2.5 mm long, cohering at the summit, separating at the base, falling at anthesis; disk of 5 connate or separate glands, 0.2-0.4 mm long; stigmas small, style conical, 0.2-0.5 mm long. Berry dark purple, globose; seeds 1-4 usually red or brown, pyriform, 4-7 mm long."[3]

"High-climbing vine with adhering bark, conspicuous tendrils, and pith continuous through node; young branches angled, puberulent. Leaves suborbicular or widely ovate, to 8 cm long or wide, glabrate or glabrous. Mature inflorescences to 5 cm long, few-fruited; berries 1-2 cm in diam.; seeds ca. 6 mm long."[3]

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

V. rotundifolia responds negatively to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plain communities. This marks it as a possible indicator species for remnant woodland.[4][5] However, it responds positively to soil disturbance by heavy silvilculture in North Carolina[6] and exhibits positive as well as negative responses to heavy silvilculture in North Florida.[7] V. rotundifolia responds negatively to soil disturbance by clearcutting and roller chopping in North Florida.[8] It exhibits no response to soil disturbance by improvement logging in Mississippi.[9] V. rotundifolia responds negatively to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[10]

Vitis rotundifolia is frequent and abundant in the Calcareous Savannas community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[11]

Phenology

V. rotundifolia has been observed flowering from March to May and in July with peak inflorescence in May.[12]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[13]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Vitis rotundifolia at Archbold Biological Station:[14]

Apidae: Apis mellifera, Bombus impatiens

Halictidae: Agapostemon splendens, Augochloropsis anonyma, A. sumptuosa, Lasioglossum placidensis

Megachilidae: Megachile brevis pseudobrevis, M. mendica, M. petulans

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 695. Print.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ Cohen, S., R. Braham, and F. Sanchez. (2004). Seed Bank Viability in Disturbed Longleaf Pine Sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.

- ↑ Conde, L.F., B.F. Swindel, and J.E. Smith. (1986). Five Years of Vegetation Changes Following Conversion of Pine Flatwoods to Pinus elliottii Plantations. Forest Ecology and Management 15(4):295-300.

- ↑ Lewis, C.E., G.W. Tanner, and W.S. Terry. (1988). Plant responses to pine management and deferred-rotation grazing in north Florida. Journal of Range Management 41(6):460-465.

- ↑ McComb, W.C. and R.E. Noble. (1982). Response of Understory Vegetation to Improvement Cutting and Physiographic Site in Two Mid-South Forest Stands. Southern Appalachian Botanical Society 47(1):60-77.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 15 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.