Pinus palustris

Common Names: Longleaf pine [1]

| Pinus palustris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Gwaltney hosted at Southeastern Flora.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Pinaceae |

| Genus: | Pinus |

| Species: | P. palustris |

| Binomial name | |

| Pinus palustris Mill. | |

| |

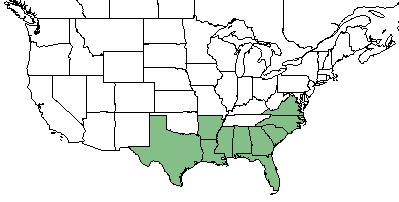

| Natural range of Pinus palustris from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonym: P. australis (Michaux)

Variety: none

Description

Pinus palustris is a perennial tree of the Pinaceae family that is native to North America. [1]

Distribution

P. palustris is found throughout the southeastern United States; specifically in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas. [1]

Ecology

Habitat

Habitat falls largely within the southeastern Atlantic coastal plain and Gulf coastal plain. They require warm, wet, and temperate climates that have a steady reliable annual precipitation of 43-69 inches. It is common in sandy, well-drained soils close to sea level. [1] P. palustris exhibits no significant response to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plains communities.[2]

Specimens have been collected from hardwood hammocks, longleaf pine scrub oak ridge, sandy soils with many oak species, and old longleaf stands. [3]

Being historically known to the southeastern coastal plains, the longleaf pine stands have been an ideal habitat for herbaceous diversity. [4]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind. [5]

Seed bank and germination

Germination needs mineral soil and 1-2 weeks after dispersal. Most germination occurs during the fall and spring. Only after the first two years of development, seedlings will begin to develop stems and growth in height begins to occur rapidly. During the first two years, the root system is developing, preparing for a rapid growth to extreme heights. [1]

Fire ecology

P. palustris requires frequent burning for a healthy environment. Without frequent burning, hardwood species will begin to overtake the habitat. The species requires burning to regenerate and seed. P. palustris has a high fire tolerance. [1]

Use by animals

Birds and small mammals eat the large seeds, ants will eat the seeds that are germinating, and razorback hogs eat the roots of the seedlings.[1]

The tree provides habitats for bobwhite quail, white tailed deer, wild turkey, and fox squirrel. [1]

Red-cockaded woodpecker will use the old growth stands for nesting. [1]

Diseases and parasites

Hogs eat the seedlings during the initial stages of development.[1]

The brown spot needle disease can cause defoliation of the P. palustris tree. It is a fungus that occurs with a build up of dead grass on the forest floor and can spread to the young trees and seedlings. Frequent burning can reduce the likelihood of this disease spreading. [1]

Conservation and Management

Frequent fire is necessary to maintain a healthy forest of P. palustris. They grow in the place of dead trees, allowing for many tree of the same age to disperse to the same area where old trees have fallen. [1]

Excessive grazing of the forest floor will reduce the P. palustris in the region. [1]

Pinus palustris stands have been declining since European settlement with an increase in logging, agricultural conversion, and suppressing natural fires that are key to the health of long-leaf pine land. [6] They were once considered the most abundant ecosystem in North America with over 37 million ha to only 1.5 ha in 1985. [7]

Cultivation and restoration

P. palustris is ideal for reforestation in the proper climates; dry, seep sands in the southeastern United States. [1]

Longleaf trees that were injured by anthropogenic activity will develop fire scars, where they were cut or sliced, after a burn. These can indicate when the region expereinced natural or prescribed burning. [8]

Soil disturbances such as soil compaction, surface scarring, and most sifgnificantly agricultural disturbances have a large impact on the longleaf pine composition in a region. [9]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 USDA Plant Database

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R.K. Godfrey, Cecil R. Slaughter, Kurt Blum, S.W. Leonard, A. S. Jensen, S. L. Beckwith, Sidney McDaniel, S. Snedaker, D. B. Ward, Patricia Elliot, L. B. Trott, J. P. Gillespie, R. Komarek, Leon Neel, K. M. Meyer, A. Townesmith, Annie Schmidt States and counties: Florida (Franklin, Leon, Putnam, Washington, Orange, Citrus, Nassau, Marion, Wakulla, Liberty) Georgia (Harris)

- ↑ Andreu, M. G., et al. (2009). "Can managers bank on seed banks when restoring Pinus taeda L. plantations in Southwest Georgia?" Restoration Ecology 17: 586-596.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Aschenbach, T. A., et al. (2010). "The initial phase of a longleaf pine-wiregrass savanna restoration: species establishment and community responses." Restoration Ecology 18(5): 762-771.

- ↑ Brockway, D. G. and C. E. Lewis (1997). "Long-term effects of dormant-season prescribed fire on plant community diversity, structure and productivity in a longleaf pine wiregrass ecosystem." Forest Ecology and Management 96: 167-183.

- ↑ Huffman, J. M. and M. T. Rother (2017). "Dendrochronological field methods for fire history in pine ecosystems of the southeastern coastal plain." Tree-Ring Research 73(1): 42-46.

- ↑ Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson (2007). A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, south Georgia, USA. Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems, Tallahassee, Tall Timbers Research Station.