Chasmanthium laxum

Common name: Slender Woodoats[1]; Slender Spikegrass[2]

| Chasmanthium laxum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Cyperales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Genus: | Chasmanthium |

| Species: | C. laxum |

| Binomial name | |

| Chasmanthium laxum (L) Yates | |

| |

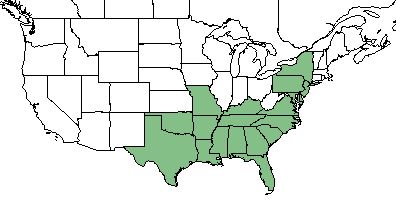

| Natural range of Chasmanthium laxum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Uniola laxa (Linnaeus) Britton, Sterns, & Poggenburg; Chasmanthium laxum (Linnaeus) Yates var. laxum

Varieties: none

Description

C. laxum is a perennial graminoid of the Poaceae family native to North America. [1] Leaves alternate, simple, and with parallel venation. Fruit type is a caryopsis, and overall root growth is fibrous.[3] Weakley notes that C. sessiliflorum is mostly morphologically similar to C. laxum and they often grow side by side.[2]

Distribution

C. laxum can be found along the southeastern coast from Texas to New York. [1]

Ecology

Habitat

C. laxum can be found in savanna-pocosin ecotones, sandhill-pocosin ecotones, moist hardwood swamps, bottomland hardwood forests, mesic hammocks, and other moist habitats.[2][4] It also occurs in upland closed-canopy forests where fire is excluded, including slope forest and upland hardwood (beech-magnolia) forest.[4] It is listed as a facultative wetland species that commonly grows in wetlands, but can also grow in non-wetland areas.[1] It is also shade-tolerant, enabling it to thrive under the canopy of other plants. [5] Other habitats it has been observed in include roadside ditches and other wet disturbed areas, low pinewoods, stream banks, in shallow water, and other shaded areas. Soils include sandy, sandy loam, loamy, and moist loam sand.[6] Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum) has a negative effect on C. laxum and overcompetes the species when the canopy is opened.[7]

Associated species: Pinus elliottii, Chasmanthium nitidum, C. latifolium, C. ornithorhynchus, Panicum sp., Pterocaulon sp., Vitis rotundifolia, Toxicodendron radicans, Gibasis pellucida, Calopogon tuberosus, Quercus geminata, Quercus nigra, Quercus sp., Liquidambar styraciflua, and others.[6][8]

Phenology

C. laxum has been observed to flower from June to August, and fruit during the same time period.[9][6]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.[10]

Fire ecology

C. laxum is not fire resistant and has no fire tolerance. [1]

Use by animals

C. laxum is highly palatable to browsing and grazing animals.[1] It consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet for large mammals and terrestrial birds.[11]

Conservation and Management

C. laxum is listed as an endangered species by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Land and Forests, and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. [1]

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 USDA Plant Database https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=CHLA6

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 5, 2019

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Florida Natural Areas Inventory 2010. Guide to the natural communities of Florida: 2010 edition. Florida Natural Areas Inventory, Tallahassee, Florida, 228 pg.

- ↑ Iglay, R. B., et al. (2010). "Effect of plant community composition on plant response to fire and herbicide treatments." Forest Ecology and Management 260: 543-548.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: March 2019. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, A. F. Clewell, S. T. Cooper, M. Darst, R. F. Doren, R.K. Godfrey, J. Good, B. F. Hansen, J. M. Kane, Herbert Kessler, Tina Kessler, R. Komarek, Mabel Kral, R. Kral, - Kurz, H. Light, G. Mahon, D. L. Martin, R. Mattson, Sidney McDaniel, Robert A. Norris, R. E. Perdue, Paul Redfearn, Jr., George Robinson, Cecil Slaughter, and J. N. Triplett, Jr. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Baker, Clay, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Hernando, Holmes, Jefferson, Leon, Levy, Marion, Okaloosa, St Johns, Taylor, Wakulla, and Walton. Georgia: Atkinson, Grady, and Thomas.

- ↑ Brewer, S. J., et al. (2012). "Do natural disturbances or the forestry practices that follow them convert forests to early-successional communities?" Ecological Applications 22: 442-458.

- ↑ Morris, M. W. (1988). "Noteworthy vascular plants from Grenada County, Mississippi." SIDA Contributions to Botany 13(2): 177-186.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 18 MAY 2018

- ↑ Creech, M. N., et al. (2012). "Alteration and Recovery of Slash Pile Burn Sites in the Restoration of a Fire-Maintained Ecosystem." Restoration Ecology 20(4): 505-516.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.