Rhynchosia reniformis

| Rhynchosia reniformis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo was taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Genus: | Rhynchosia |

| Species: | R. reniformis |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhynchosia reniformis DC. | |

| |

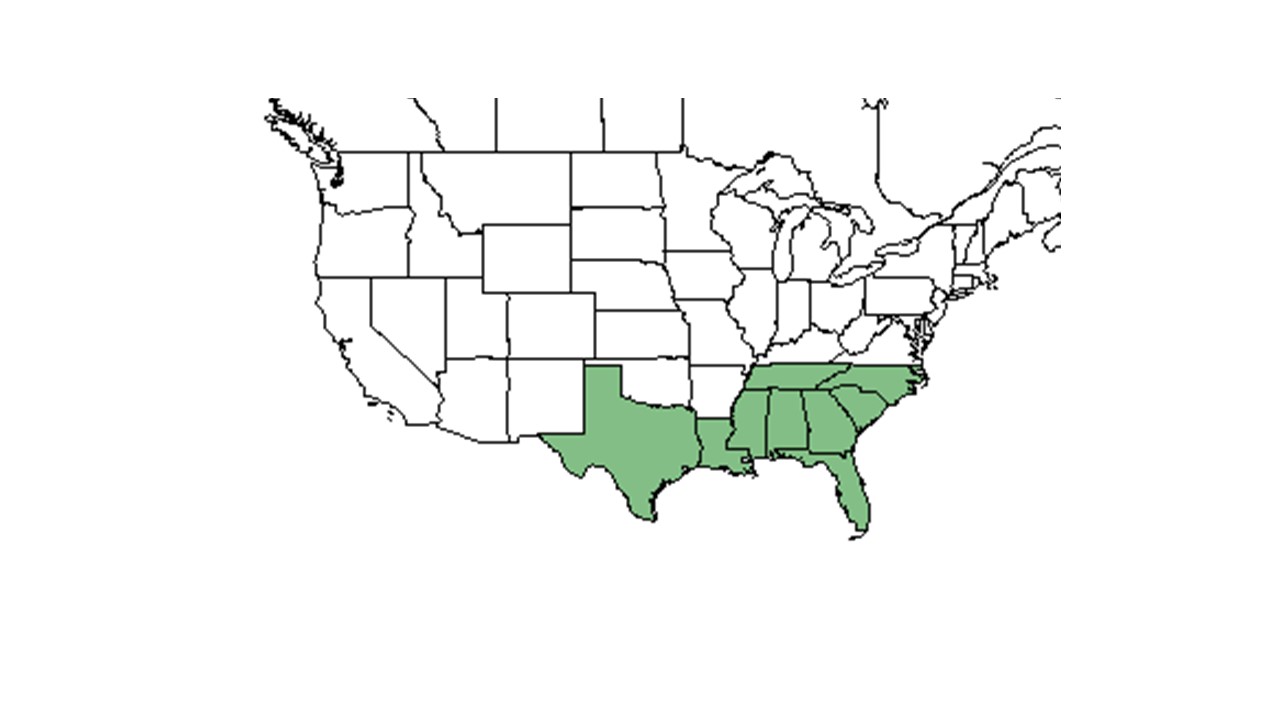

| Natural range of Rhynchosia reniformis from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Dollarleaf (Nelson 2005), Dollarweed

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonym: Rhynchosia simplicifolia (Walter) Wood

Description

“Erect, trailing or climbing, perennial herbs or shrubs. Leaves pinnately 3-foliolate or occasionally 1-foliolate; leaflets usually entire and often bearing amber glands, usually estipellate; stipules ovate to lanceolate. Flowers papilionaceous, rarely solitary or in pairs but usually in axillary or occasionally also terminal racemes, several to numerous, loose to compactly clustered, pedicellate, each subtended by a caduceus bract. Calyx tube campanulate or tubular, nearly regular, lobes equal or nearly so in size but with the 2 uppermost partially united; petals yellow in ours, often equaling or even shorter than the calyx; stamens diadelphous, 9 and 1. Legume usually oblong and flattened, 1-2 seeded, dehiscent." [1]

"Erect herb 0.5-2.5 dm tall with strongly angled, densely short-pubescent stems. Leaves mostly 1-foliolate or rarely the lowermost 3-foliolate; leaflets suborbicular to reniform, 2-5 cm long, usually wider than long, thick and conspicuously reticulate, sparsely to densely pubescent especially along the veins on both surfaces, inconspicuously beset with numerous, minute, amber glands above and below, stipels persistent, 1.5-2.5 mm long; stipules persistent, linear-lanceolate, 5-10 mm long. Racemes axillary and terminal, sessile or peduncles to 2 cm long with rachises mostly 1-3 cm long, with numerous, closely clustered flowers on pedicels 1.5-3 mm long each subtended by a linear-subulate bract 3-5 mm long. Calyx densely hirsute to villous with numerous, inconspicuous, amber glands, tube 1.5-2 mm long, lobes subequal, lanceolate, 6-9 mm long, long-acuminate to subulate; petals yellow, 6-8 mm long. Legume 1-1.8 cm long, 5-7 mm broad, densely short-pubescent, inconspicuously glandular."[1]

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

In the Coastal Plain region, R. reniformis can be found in burned longleaf pine-wiregrass stands, burned upland longleaf pine forests, loamy sands of longleaf pine-oak scrubs, sandhills, savannas, sandy open areas, sandpine flatwoods, pineflatwoods on limerock, recently burned scrubs of cutover pinewoods, and turkey oak sand ridges. [2] [3] It can also be found in open powerlines, clobbered slash pine forests, fallow longleaf pine-scrub oaks, and railroad embankments. Associated species include Galactia mollis, Desmodium floridanum, Desmodium strictum, R. tomentosa, Pinus palustris, Aristida stricta, slash pine, sand pine, Lactuca floridana, Serenoa repens, turkey oak, Acanthospermum, Polygala and Onosmodium. [2]

Soil types include dry sand, sandy loam, loamy sand, limerock and gravelly sand. [2]

Phenology

It inconsistently flowers from April to September. [3]

Seed dispersal

This species disperses by being consumed by vertebrates (being assumed). [4]

Fire ecology

R. reniformis is a legume found in frequently burned longleaf pine savannas. [5] [6] It was observed to resprout one month after a fire in July of 1993.[7] In a burning x no shade treatment, R. reniformis was found to have elevated levels of N2-fixation. [6] Herbivory damage for R. reniformis does not increase with time since fire. [8]

Conservation and management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 636. Print.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: July 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Robert L. Lazor, Steve L. Orzell, Edwin L. Bridges, Gary R. Knight, James R. Burkhalter, R.K. Godfrey, A. F. Clewell, Cheryl Vaughan, Robert Kral, Mable Kral, Gwynn W. Ramsey, R. S. Mitchell, Travis MacClendon, Karen MacClendon, Rodie White, Walter Kittredge, Kevin Oakes, Richard R. Clinebell II, Clarke Hudson, Charles M. Allen, Cecil R Slaughter, H. R. Reed, A. B. Seymour, F. S. Earle, S. B. Jones, Carleen Jones, S. W. Leonard, A. E. Radford, Henrietta Laing, Delzie Demaree, Lisa Keppner. States and Counties: Florida: Baker, Calhoun, Clay, Dade, Escambia, Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Hernando, Highlands, Jackson, Jefferson, Lee, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Okaloosa, Santa Rosa, St. Johns, Seminole, Suwannee, Union, Wakulla, Walton, Washington. Georgia: Baker, Grady, Seminole, Thomas. Mississippi: Clarke, Harrison, Ocean Springs, Pearl River, Pike. Louisiana: Allen. North Carolina: Harnett, Moore. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nelson, Gil. East Gulf Coastal Plain. a Field Guide to the Wildflowers of the East Gulf Coastal Plain, including Southwest Georgia, Northwest Florida, Southern Alabama, Southern Mississippi, and Parts of Southeastern Louisiana. Guilford, CT: Falcon, 2005. 184. Print.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Brewer, J. S. and S. P. Cralle 2003. Phosphorus addition reduces invasion of a longleaf pine savanna (southeastern USA) by a non-indigenous grass (Imperata cylindrica). Plant Ecology 167: 237-245.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hiers, J. K. and R. J. Mitchell 2007. The influence of burning and light availability on N-2-fixation of native legumes in longleaf pine woodlands. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 134: 398-409.

- ↑ Pavon, Milton Lara (1995). "Diversity and response of ground cover arthropod communities to different seasonal burns in longleaf pine forests." A Master's thesis.

- ↑ Knight, T. M. and R. D. Holt 2005. Fire generates spatial gradients in herbivory: an example from a Florida sandhill ecosystem. Ecology 86: 587-593.