Galactia regularis

| Galactia regularis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo was taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Galactia |

| Species: | G. regularis |

| Binomial name | |

| Galactia regularis (L.) Britton, Sterns & Poggenb. | |

| |

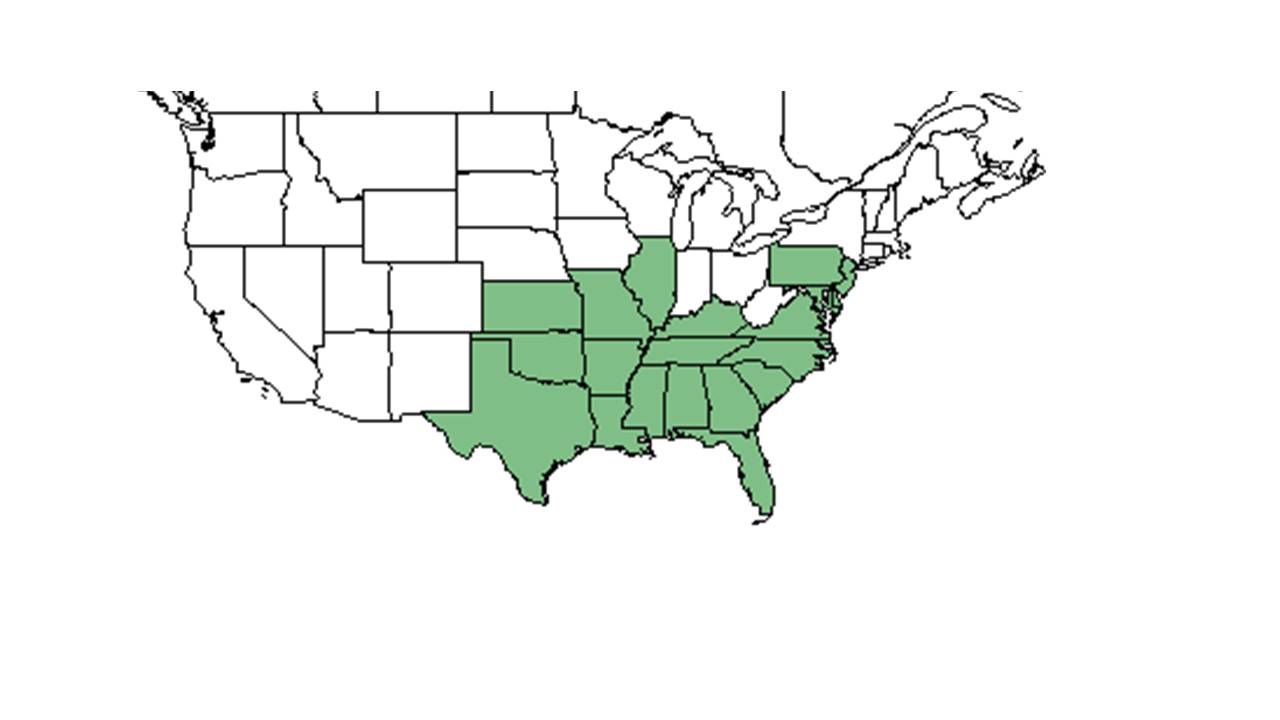

| Natural range of Galactia regularis from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: eastern milkpea

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Galactia volubilis (Linnaeus) Britton; G. macreei M.A. Curtis; G. volubilis

Description

G. regularis is a prostrate perennial with showy violet-purple flowers, frequently found climbing over bushes.[1] Stems have been observed to twine on low shrubs.[2] It has been documented as a prostrate structure. It is strongly paraheliotropic.[3]

Generally, the genus Galactia are "trailing or twining, climbing, perennial, herbaceous or woody vines or erect, perennial herbs or rarely shrubs. Leaves 1-pinnate, usually 3-foliolate (or rarely 1-,5-7-,9-folilolate); leaflets entire, petiolulate, stipellate. Racemes axillary, pedunculate with few to numerous, papilionaceous flowers borne solitary or 2-several at a node, ech subtended by a bract and fusion of the 2 uppermost, with the laterals usually shorter than the uppermost and lowermost; petals usually red, purple, pink or white; stamens diadelphous or elsewhere occasionally monadelphous; ovary sessile or shortly stipitate. Legume oblong-linear to linear, few-many seeded, compressed, straight or slightly curbed, dehiscent with often laterally twisting valves."[4]

Specifically, for this species, G. regularis, they are "trailing, perennial herb with minutely appressed-pubescent to glabrate stems, 0.4-1.2 m long. Leaves 3-foliolate, rachis 3-18 mm long; leaflets oblong to elliptic or oblong-lanceolate, (1.2) 2-3.5 (5) cm long, glabrous, or nearly so, above and glabrous to appressed-pubescent beneath. Racemes with glabrous to appressed short-pubescent peduncles and rachises (1) 3-13 cm long; flowers few to many, each on a puberulent pedicel 1-5 mm long subtended by ovate to triangular-subulate bracts ca. 1 mm long; bractlets triangular to linear-subulate, 0.8-1.5 (3) mm long. Calyx glabrous or sparsely appressed-pubescent, tube 2-3.5 mm long, lobes 3-6 mm long; petals reddish purple, the standard 1.2-1.8 cm long. Legume densely appressed-pubescent, 2-5 cm long, 4-5 cm broad."[4]

Distribution

It occurs in pinelands and sandy woods from New York to Florida and Mississippi.[1] Occurs in a Pinus elliottii plantation in South Carolina.[5]

Ecology

Habitat

Galactia regularis has been documented in open sand ridges, open cedar glades, dry prairies, dry upland woods, along rocky banks, scrub oak-wiregrass ridges, shell ridge in a brackish marsh, dry grassy scrub border of a cypress swamp, open oak-hickory woods of a bog boarder, pine flatwoods at the edges of pond cypress wetland, edge of a floodplain woodland on a natural levee, and mature longleaf pine-wiregrass stand that is frequently burned.[2] It can be found in xeric areas with hot, wet summers and mild, dry winters.[6] G. regularis has been documented in pine sandhill communities.[7] It has also been observed in shrublands.[6]

In disturbed habitats G. regularis has been found growing in areas of clay with sandstone that have been recently cleared and bulldozed along with developed locations.[2]

Soils range from sand to sandy loam.

Species that have been associated with G. regularis are Elephantopus, Yucca, bahia grass, centipede grass, Galactia volubilis and Rhynchosia difformis.[2]

Phenology

Flowers June through November.[2]

Seed bank and germination

Maximum germination was observed for G. regularis at the 80 degrees Celsius dry heat shock treatment. Wet heat (boiling water) treatments, however, resulted in 100% mortality of seeds.[8] Soil scarification seems to impede germination.[5] It reproduces by resprouting after fire.[9]

Fire ecology

In a field study of vegetation change in the Florida scrub, G. regularis increased in abundance post fire.[10] However, this increase may not be the direct result of fire. Heat shock germination may play a role in its post-fire recruitment.[8] The amount of G. regularis decreased after a spring burn; decreased slightly after a summer burn; and increased in the control plots.[11] A total of 24 plants in four new quadrants were recruited postburn study in the Florida scrub – Lake Wales Ridge area.[10]

In previous studies conducted by Cushwa and his collegues determined that leguminous plants and their seeds respond best to hot, or high temperature, fires. Cuswha and his team also conducted laboratory tests indicating that the legume species will germinate the best when hit by moist heat, such as a prescribed fire being conducted on a day that is 80 degrees Celsius.[11]

As an herbaceous vine, the amount of groundcover of G. regularis increased slightly when the area has not been burned (controlled treatment). The amount of ground cover decreased from ~58 to 23% after a burn.[9]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Galactia regularis at Archbold Biological Station: [12] Apidae: Apis mellifera, Bombus impatiens, Svastra atripes

Halictidae: Augochlorella aurata, Augochloropsis metallica, A. sumptuosa, Nomia maneei

Megachilidae: Anthidiellum notatum rufomaculatum, A. perplexum, Anthidium maculifrons, Coelioxys germana, C. sayi, Megachile albitarsis, M. brevis pseudobrevis, M. brimleyi, M. deflexa, M. exilis parexilis, M. georgica, M. integra, M. mendica, M. petulans

Sphecidae: Trypargilum clavatum johannis

Vespidae: Stenodynerus fundatiformis

Use by animals

On occasion, occurred in White-tailed deer’s diet[13]. Seeds of G. regularis have been found in stomachs of the bobwhite and has been considered an important food[1].

Diseases and parasites

G. regularis reposnded moderately resistant to a root-knotnematodes study. A nematode, M. incognita, showed an immune response to the root galls and egg masses in the 2004 study but only a highly resistant response in 2001[14].

Conservation and management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Graham, E. H. (1941). Legumes for erosion control and wildlife. Washington, USDA

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: July 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, H. E. Ahles, Tom Barnes, Michael B. Brooks, Robert W. Simons, Dianna Hall, R. Kral, R. K. Godfrey, Sidney McDaniel, R. A. Norris, H. R. Reed, Cecil R. Slaughter, Frankie Snow, A. E. Redford, C. Simon, A. A. Eaton, Robert L. Lazor, Bruce Hansen, JoAnn Hansen, W. A. Silveus, A. F. Clewell, Robert Blaisdell, O. Lakela, George R. Cooley, Richard J. Eaton, Daniel B. Ward, Paul O. Schallert, A. H. Curtiss. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Brevard, Clay, Dixie, Duval, Escambia, Franklin, Flagler, Gadsden, Hillsborough, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Nassau, Osceola, Putnam, Sarasota, St. Johns, Taylor, Wakulla, Washington. Georgia: Camden, Coffee, Grady. Mississippi: Pearl River, Oktibbeha. North Carolina: Alexander. South Carolina: Hampton. Virginia: Pulaski. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ KMR observation at Pebble Hill Plantation, Georgia in July.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 643-4. Print.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Mou, P., R. H. Jones, et al. (2005). "Regeneration strategies, disturbance and plant interactions as organizers of vegetation spatial patterns in a pine forest." Landscape Ecology 20: 971-987.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hawkes, C. V. and E. S. Menges (2003). "Effects of lichens on seedling emergence in a xeric Florida shrubland." Southeastern Naturalist 2: 223-234.

- ↑ Downer, M. R. (2012). Plant species richness and species area relationships in a Florida sandhill community. Integrative Biology. Ann Arbor, MI, University of South Florida. M.S.: 52.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bolin, J. F. (2009). "Heat shock germination responses of three eastern North American temperate species." Castanea 74: 160-167. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "bolin" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 9.0 9.1 Reinhart, K. O. and E. S. Menges (2004). "Effects of re-introducing fire to a central Florida sandhill community." Applied Vegetation Science 7: 141-150.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Weakley, C.W. and E.S. Menges. 2003. Species and vegetation responses to prescribed fire in a long-unburned, endemic-rich Lake Wales ridge scrub. J. Torrey Bot. Soc. 130: 265-282. Bolin, J. F. (2009). "Heat shock germination responses of three eastern North American temperate species." Castanea 74: 160-167.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Cushwa, C. T., M. Hopkins, et al. (1970). Response of legumes to prescribed burns in loblolly pine stands of the South Carolina Piedmont. Asheville, NC, USDA Forest Service, Research Note SE-140: 6.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Gee, K. L., M. D. Porter, et al. (1994). White-tailed deer : their foods and management in the cross timbers. Ardmore, OK, Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation.

- ↑ Quesenberry, K. H., J. M. Dampier, et al. (2008). "Response of native southeastern U.S. legumes to root-knot nematodes." Crop Science 48: 2274-2278.