Ipomoea pandurata

| Ipomoea pandurata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Solanales |

| Family: | Convolvulaceae |

| Genus: | Ipomoea |

| Species: | I. caroliniana |

| Binomial name | |

| Ipomoea pandurata (L.) G. Mey. | |

| |

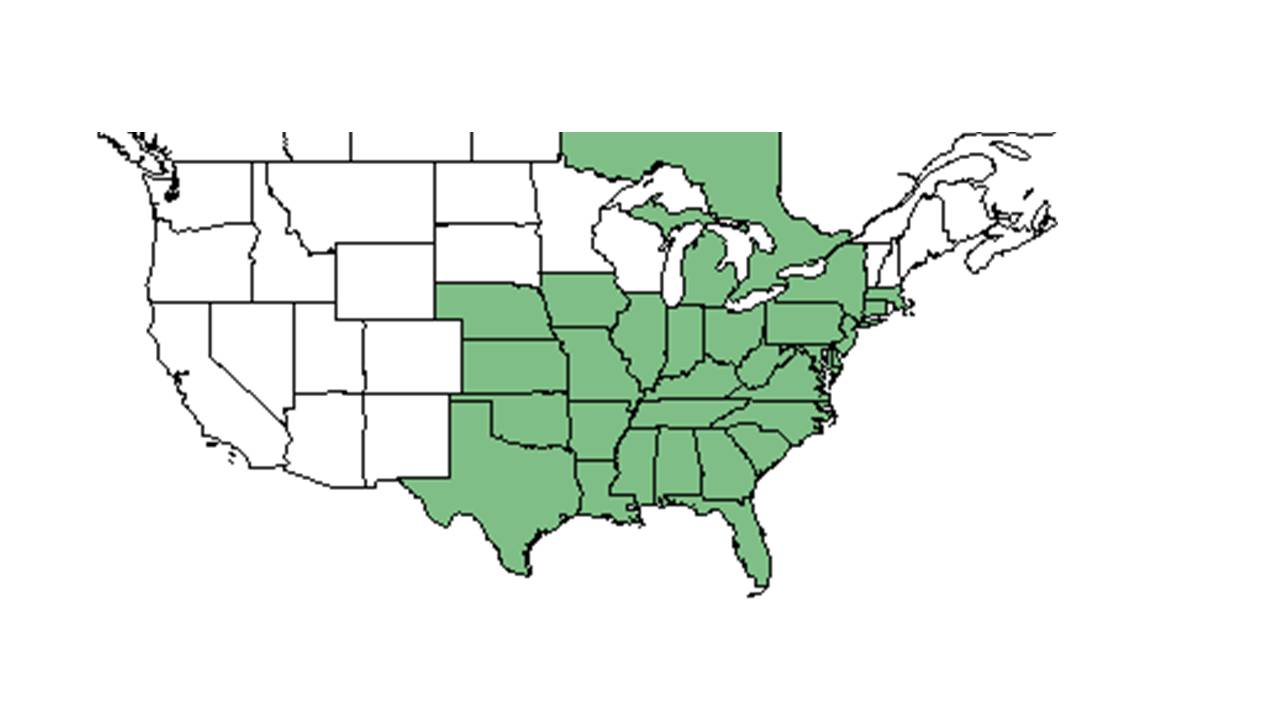

| Natural range of Ipomoea pandurata from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Common name: Carolina indigo

Description

Ipomoea pandurata, a perennial morning glory, has a large storage root and heart-shaped leaves (fig. 2). The plant forms one or more trailing vines that will grow along any surface. Produces a new shoot every year.[1]

"Herbaceous annual or perennial vines, or rarely a shrubby perennial. Flowers axillary, solitary or in 2-5 flowered cymes. Calyx lobes 5, often imbricate; corolla campanulate to funnel-form, or salverform in 2 species; stamens 5, inserted in the corolla tube alternate with the lobes; stigma globose, entire or slightly lobed, style 1, ovary 2-or-4 locular. Capsule 2-4 valved; seeds 2-6, sometimes villous. A large genus of primarily tropical plants, some of which were introduced as horticultural plants and have escaped to become noxious weeds." - Radford et al 1964

"Trailing, glabrate or weakly pubescent perennial from an enlarged root. Leaves ovate, entire or pandurate, 3.5-8 cm long, 2.5-8 cm wide, cordate, often pubescent beneath. Peduncles 1-5 flowered; pedicel glabrous, stout; calyx lobes coriaceous, oblong-elliptic, 12-15 mm long, glabrous, strongly imbricate; corolla campanulate, 6-8 cm long, about sa broad, the limb white, the tube lavender within; anthers 5-7 mm long, stamens and stigma included. Capsule ovoid, ca. 1 cm long; seeds villous on the angles." - Radford et al 1964

Distribution

Ecology

Net photosynthesis did not differ significantly among the disturbance levels. However, whether a site was burned in the previous year clearly influenced net photosynthesis. Low sites that had been burned recently tended to have lower net photosynthesis than unburned low disturbance sites. Recently burned medium sites had much higher net photosynthesis than unburned medium sites. The highest rate of photosynthesis occurred at the burned medium and high sites (Freeman et al 2004). We found that recent prescribed burning, a management tool used to promote the growth of longleaf pine in this ecosystem, elevated levels of net photosynthesis for both ground cover species that we examined as stress indicators. In species with underground perennating organs, burning has been shown to stimulate rates of net photosynthesis (Freeman et al 2004). Although a flush of nutrients immediately follows burning, with an increase in mineralized nitrogen potentially persisting for up to a year (Freeman et al 2004), most of the increase in net photosynthesis is believed to be the result of a change in the ratio of roots to shoots. The new smaller shoots have a proportionately larger root system that provides ample water and nutrients (Freeman et al 2004).

Habitat

This species does well in canopy openings in dry woods and thickets.(Freeman et al 2004). Grows in well drained uplands (FSU Herbarium). This species has also been observed to grow in open pine-oak scrub, along roadsides, and in open fields (FSU Herbarium).

Phenology

Flowers in June (FSU Herbarium).

Seed dispersal

Seed bank and germination

Fire ecology

It appeared growing after a burn at the end of May/early June.[2] It occurs in mostly longleaf pine communities that are annually burned as well (FSU Herbarium).

Pollination

Use by animals

Diseases and parasites

Conservation and Management

Physical habitat disturbance was caused by activities associated with infantry training, including mechanized elements (tanks and personnel carriers) and foot soldiers. In addition, we examined the influence of prescribed burns and microhabitat effects (within meter-square quadrats centered about the plant) on these measures of plant stress. Net photosynthesis declined with increasing disturbance in the absence of burning for both species. However, when sites were burned the previous year, net photosynthesis increased with increasing disturbance.[1]

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R. F. Doren, R. Komarek, R. A. Norris, and Gwynn W. Ramsey. States and Counties: Florida: Gadsden and Leon. Georgia: Brooks, Grady, and Thomas.

Freeman, D. Carl, Michelle L. Brown, Jeffrey J. Duda, John H. Graham, John M. Emlen, Anthony J. Krzysik, Harold E. Balbach, David A. Kovacic, and John C. Zak. "Photosynthesis and Fluctuating Asymmetry as Indicators of Plant Response to Soil Disturbance in the Fall‐Line Sandhills of Georgia: A Case Study Using Rhus Copallinum and Ipomoea Pandurata." International Journal of Plant Sciences 165.5 (2004): 805-16. Web. 24 June 2013.

Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 864-8. Print.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedFreeman 2004 - ↑ Arata, A. A. (1959). "Effects of burning on vegetation and rodent populations in a longleaf pine-turkey oak association in north central Florida." Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences 22: 94-104.