Eupatorium hyssopifolium

| Eupatorium hyssopifolium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Eupatorium |

| Species: | E. hyssopifolium |

| Binomial name | |

| Eupatorium hyssopifolium L. | |

| |

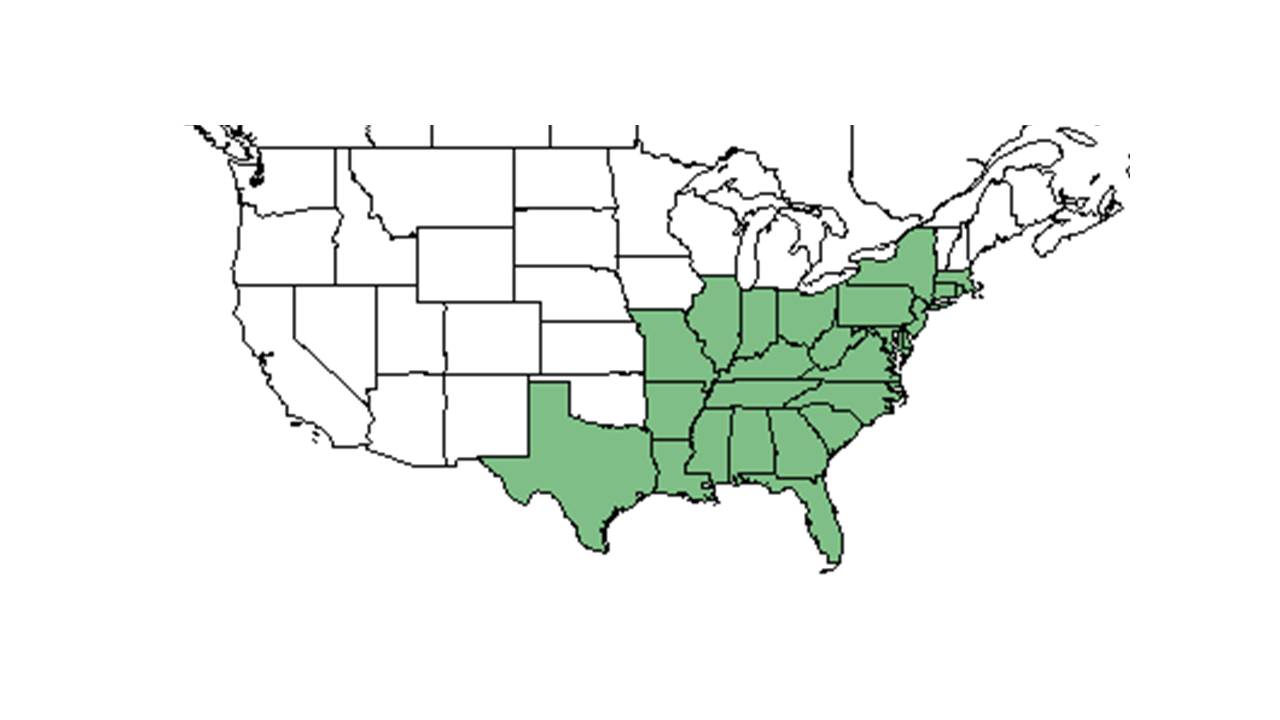

| Natural range of Eupatorium hyssopifolium from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: hyssopleaf thoroughwort; hyssopleaf Eupatorium

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Eupatorium hyssopifolium var. hyssopifolium[1]

Varieties: E. hyssopifolium var. calcaratum Fernald & Schubert; E. lecheifolium Greene; E. sessilifolium[1]

Description

A description of Eupatorium hyssopifolium is provided in The Flora of North America.

Distribution

E. hyssopifolium is generally distributed from Massachusetts south to Georgia and west to Tennessee and Louisiana.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Habitats of this species include pastures, roadbanks, fields and disturbed areas, and dry woodlands.[1] It is found in Longleaf pine-Turkey oak sand ridges, Longleaf pine sandhills and flatwoods, pine-palmetto flatwoods, Turkey oak scrubs, Longleaf pine-wiregrass savannas, and in open meadows. It is also found in human disturbed areas such as old fields, roadsides and areas that have been clear cut and bulldozed. It requires high levels of light. It is associated with sandy loam, sand-clay loam, and sandy soil types.[2] It is negatively correlated with soil disturbance.[3] As well, it is considered an indicator species of the clayhill longleaf woodlands in northern Florida.[4] E. hyssopifolium is a dominant plant species in old field sites rather than native ground-cover in the Red Hills region of northern Florida and southern Georgia.[5] However, E. hyssopifolium was found to be neutral in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[6]

Associated species include Andropogon, Pinus palustris, Quercus laevis, Quercus stellata, Aristida sp., Helianthus sp., and Conoclinium coelestinum.[2]

Eupatorium hyssopifolium is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[7]

Phenology

Generally, this species flowers from late July until October.[1] It has been observed flowering from July to November.[2]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind. [8]

Fire ecology

Overall, E. hyssopifolium increases in occurrence in response to fire disturbance.[9] It increased in frequency after 12 prescribed burns over an 18 year period.[10] It occurs in pinelands and savannas that are burned annually.[2] E. hyssopifolium is most commonly found in habitats with high fire return intervals,[11] such as those on the Pebble Hill plantation in north Florida that are known to withstand repeated annual burning.[12][13]

Herbivory and toxicology

The species attracts various birds.[14] Additionally, this species has been observed to host bees such as Bombus fraternus (family Apidae) and aphids such as Uroleucon sp. (family Aphididae).[15]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

E. hyssopifolium is listed as endangered by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Natural Areas and Preserves.[16] It is also listed as endangered by the Illinois Endangered Species Protection Board.[17]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: R. Lazor, Loran C. Anderson, J. P. Gillespie, R.K. Godfrey, Gary R. Knight, R. Kral, Angus Gholson, A. F. Clewell, N. C. Henderson, Victoria I. Sullivan, Carol Havlik, Richard S. Mitchell, R. Komarek, R. A. Norris, and R. F. Doren. States and Counties: Florida: Escambia, Gadsden, Jackson, Leon, Madison, Taylor, and Wakulla. Georgia: Grady and Thomas.

- ↑ Kay, C. A. R., et al. (1978). "Vegetative cover in a fallow field: Responses to season of soil disturbance." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 105(2): 143-147.

- ↑ Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson (2007). A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, south Georgia, USA. Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems, Tallahassee, Tall Timbers Research Station.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Niering, W. A. and G. D. Dreyer (1989). "Effects of prescribed burning on Andropogon scoparius in postagricultural grasslands in Connecticut." American Midland Naturalist 122: 88-102.

- ↑ Niering, W. A. and G. D. Dreyer (1989). "Effects of prescribed burning on Andropogon scoparius in postagricultural grasslands in Connecticut." American Midland Naturalist 122: 88-102.

- ↑ Mehlman, D. W. (1992). "Effects of fire on plant community composition of North Florida second growth pineland." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 119(4): 376-383.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 10, 2019

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 10 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ Board, I. E. S. P. (2015). "Checklist of Illinois Endangered and Threatened Animals and Plants."