Desmodium obtusum

| Desmodium obtusum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Desmodium |

| Species: | D. obtusum |

| Binomial name | |

| Desmodium obtusum (Muhl. ex Willd.) DC. | |

| |

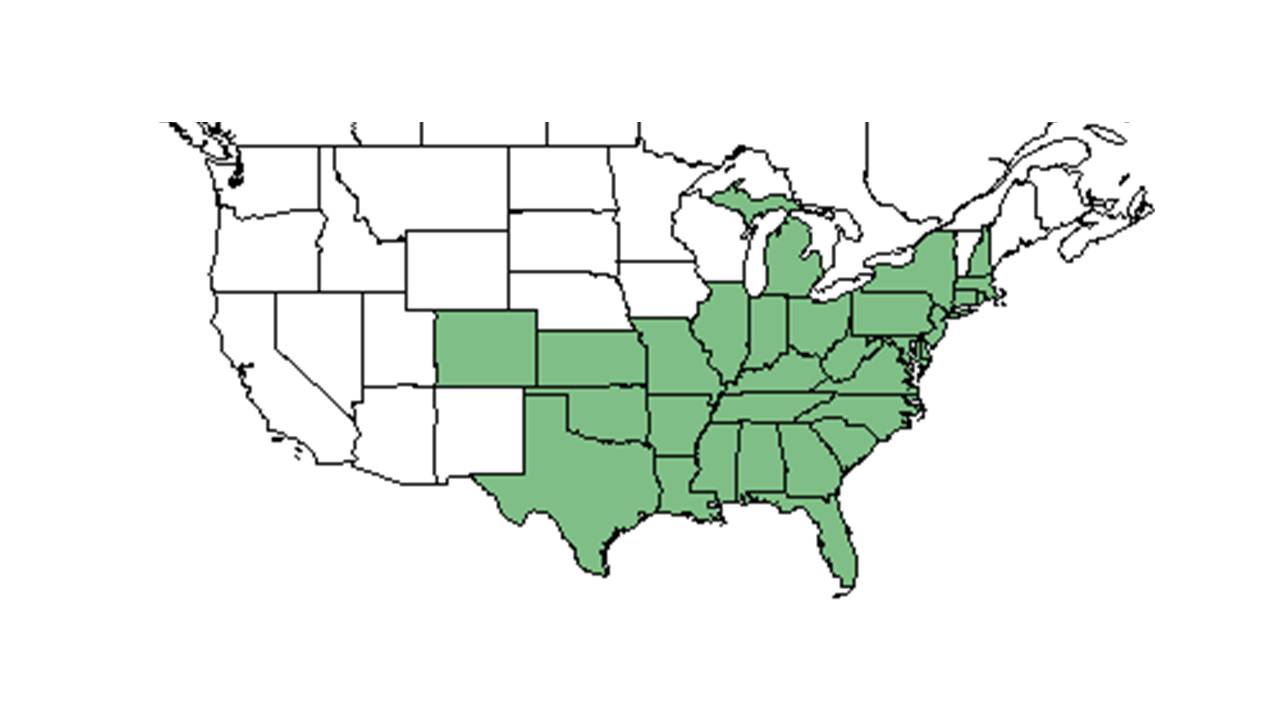

| Natural range of Desmodium obtusum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: stiff tick-trefoil

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Desmodium marilandicum (Linnaeus) A.P. de Candolle var. lancifolium (Fernald & B.G. Schubert) H. Ohashi; Desmodium rigidum (Elliott) A.P. de Candolle; Meibomia rigida (Elliott) Kuntze[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

Generally, for Desmodium genus, they are "annual or perennial herbs, shrubs or small trees. Leaves 1-5 foliolate, pinnately 3-foliolate in ours or rarely the uppermost or lowermost 1-foliolate; leaflets entire, usually stipellate; stipules caduceus to persistent, ovate to subulate, foliaceous to setaceous, often striate. Inflorescence terminal and from the upper axils, paniculate or occasionally racemose; pedicel of each papilionaceous flower subtended by a secondary bract or bractlet, the cluster of 1-few flowers subtended by a primary bract. Calyx slightly to conspicuously 2-lipped, the upper lip scarcely bifid, the lower lip 3-dentate; petals pink, roseate, purple, bluish or white; stamens monadelphous or more commonly diadelphous and then 9 and 1. Legume a stipitate loment, the segments 2-many or rarely solitary, usually flattened and densely uncinated-pubescent, separating into 1-seeded, indehiscent segments." [2]

Specfically, for D. obtusum species, they are "erect perennial; stems 0.5-1.2 m tall, densely uncinate-pubescent. Terminal leaflets oblong to ovate or elliptic, (0.8) 2-3.5 (4.5) cm long, mostly 1,8-2.2 times as wide, short-puberulent to short-pubescent or glabrate above, sparsely to densely short-pubescent and reticulate below; stipules soon deciduous, lance-attenuate to ovate-lanceolate, 2-6 mm long; stipels persistent. Inflorescence usually paniculate, short-pubescent to pilose; petals purplish, ca. 4-6 mm long; stamens diadelphous. Loment of 1-4 weakly obovate to suborbicular segments, each 3-5 mm long, 2.5-2.5 mm broad, very slightly convex along the upper suture and broadly rounded below, densely uncinulate-puberulent on both sides and sutures; stipe about 1.5-3.5 mm long, longer than the calyx tube but shorter than the lobes and the stamina remnants." [2]

Distribution

Found north to New Hampshire south to Florida and west to Colorado.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

It is distributed widely throughout the eastern U.S. and southern Great Plains.[4] General habitats include fields, woodland borders, dry pine woodlands, and disturbed areas.[5] Occurs in frequently burned longleaf and shortleaf pine-oak-hickory upland native and old-field communities (Ultisols),[6][7] longleaf pine-turkey oak sandhills (Entisols), longleaf and slash pine flatwoods (Spodosols), and in limestone outcrops.[7] It is fire-tolerant.[6] Occurs in both native areas and areas with recent soil disturbance. Some seem to have ruderal-growing tendencies. Occurs on a wide range of soils from loamy sand to clayey soils; and in sites ranging from xeric to moist. D. obtusum was found to be an increaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[8]

Associated species include Desmodium glabellum and Gnaphalium obtusifolium.[7]

Phenology

D. obtusum flowers from June to September and fruits from August through October.[5] In the southeastern coastal plain it has been observed to flower from September to October with peak inflorescence in October, and fruit from September to November.[9][7]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by translocation on animal fur or feathers. [10]

Fire ecology

Populations of Desmodium obtusum have been known to persist through repeated annual burns,[11][12] and thrives in frequently burned (1-2 year interval) habitats, occurring primarily in high-light environments but can also tolerate partial shade.[7] A study by Kush in 2000 found that D. obtusum benefits from spring seasonality burns.[13]

Pollination

Floral visitors include bumblebees (Bombus sp.), longhorned bees (Melissodes sp.), and leaf cutter bees (Megachile sp.).[14] Desmodium obtusum has been observed to host sweat bees such as Nomia maneei (family Halictidae).[15]

Herbivory and toxicology

D. obtusum consists of approximately 10-25% of the diet for large mammals and terrestrial birds.[16] Insect feeders include skipper caterpillars as Achalarus lyciades (hoary edge), Thorybes bathyllus (southern cloudywing), Thorybes pylades(northern cloudywing), and Epargyreus clarus (silver-spotted skipper); the caterpillars of the butterflies Everes comyntas(eastern tailed blue) and Strymon melinus (gray hairstreak). Seeds are eaten by gamebirds (bobwhite, wild turkey) and rodents (white-footed mouse, deer mouse). White-tailed deer and cottontail rabbits eat the foliage.[14]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

This species is listed as endangered by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, by the New Hampshire Division of Forests and Lands, and by the New York Division of Land and Forests.[4] For quail management, D. obtusum can be used as supplemental food planting.[17]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 604-10. Print.

- ↑ [[1]]NatureServe. Accessed April 21, 2016

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 26 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Cushwa, C. T. (1970). Response of legumes to prescribed burns in loblolly pine stands of the South Carolina Piedmont. Asheville, NC, USDA Forest Service.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: R.K. Godfrey, John Morrill, Loran C. Anderson, A. F. Clewell, R. Kral, J. P. Gillespie; D. C. Hunt, R. Komarek, Sidney McDaniel, Samuel B. Jones, Jr., Harry E. Ahles, J A Duke; Charles S. Wallis, William B. Fox, Lloyd H. Shinners, and Eula Whitehouse. States and Counties: Alabama: Greene and Macon. Florida: Calhoun, Escambia, Franklin, Jackson, Leon, Madison, and Wakulla. Georgia: Baker, Colquitt, Grady, and Thomas. Louisiana: Bossier. Mississippi: Lamar. North Carolina: Mecklenburg and Robeson. Oklahoma: Sequoyah. Texas: Freestone.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 26 APR 2019

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 [[2]]Illinois Wildflowers. Accessed: April 21, 2016

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [3]

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Hamrick, R., et al. (2007).