Vaccinium myrsinites

| Vaccinium myrsinites | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Pat Howell, Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Ericaceae |

| Genus: | Vaccinium |

| Species: | V. myrsinites |

| Binomial name | |

| Vaccinium myrsinites Lam. | |

| |

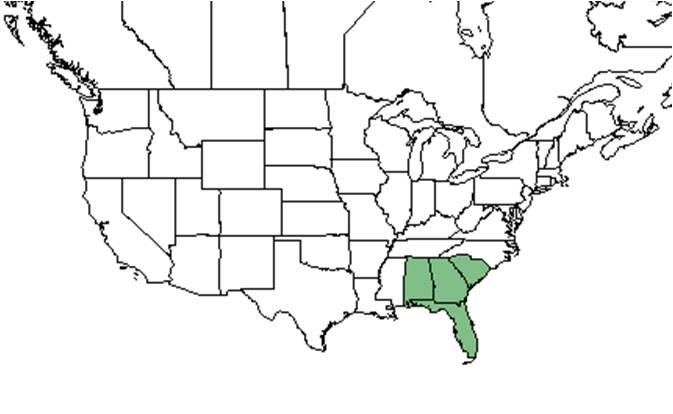

| Natural range of Vaccinium myrsinites from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Shiny blueberry, Southern evergreen blueberry

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonym: Cyanococcus myrsinites (Lamarck) Small var. myrsinites.[1]

Description

A description of Vaccinium myrsinites is provided in The Flora of North America.

Vaccinium myrsinites does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its taproot.[2] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an non-structural carbohydrate concentration of 97.7 mg/g (ranking 53 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 34.7% (ranking 78 out of 100 species studied).[2]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Vaccinium myrsinites has taproots with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 0.335 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 97.7 mg g-1.[3]

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

V. myrsinites has been found in sand pine scrub, pine-live oak woods, sand of pine ridges, pine flatwoods, sandy pine-palmetto woods, wet prairies, scrub oak sand ridges, and slash pine flatwoods.[4] It is also found in disturbed areas including along roadsides, open powerline corridors, and logged pinewoods.[4]

Associated species: Linum, V. floridanum, and Sisyrinchium.[4]

V. myrsinites reduced its crown cover and had a mixed response in its change in biomass in response to heavy silviculture in north Florida.[5] V. myrsinites became absent in response to military training in west Georgia.[6] It decreased its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in southwest Georgia savannas.[7] It also decreased its cover in response to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in north Florida flatwoods forests.[8] V. myrsinites showed change in foliar cover that was variable and dependent on time since disturbance in response to soil disturbance by clearcutting and roller chopping in north Florida.[9]

Vaccinum myrsinites is frequent and abundant in the Xeric Flatwoods, North Florida Mesic Flatwoods, and Central Florida Flatwoods/Prairies community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[10]

Phenology

V. myrsinites has been observed to flower January to April with peak inflorescence in March.[11]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[12] In particular, it has been found to be dispersed by the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus).[13]

Fire ecology

Populations of Vaccinium myrsinites have been known to persist through repeated annual burning.[14]

Pollination

Vaccinium myrsinites has been observed at the Archbold Biological Station with bees such as Nomada fervida (family Apidae), sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as Agapostemon splendens, Augochlorella aurata, A. gratiosa, Augochloropsis anonyma, A. metallica, A. sumptuosa, and Lasioglossum pectoralis, wasps such as Leucospis slossonae (family Leucospididae), leafcutting bees from the family Megachilidae such as Coelioxys sayi, Megachile brevis pseudobrevis, and M. mendica , thread-waisted wasps such as Ectemnius rufipes ais (family Sphecidae), and wasps from the Vespidae family such as Parancistrocerus salcularis rufulus, Pseudodynerus quadrisectus, Stenodynerus fundatiformis, S. histrionalis rufustus, and S. lineatifrons.[15] Additionally, this species has been observed with leafcutting bees such as Osmia sandhouseae.[16]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Vaccinium myrsinites produces a berry that can be eaten raw or cooked into goods such as jellies or pies.[17]

Photo Gallery

Flowers of Vaccinium myrsinites Photo by Shirley Denton (copyrighted- use by photographer’s permission only), Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants

References and notes

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, George R. Cooley, Robert K. Godfrey, O. Lakela, Robert J Lemaire, Joseph Monachino, Sidney McDaniel, and L. B. Trott. States and counties: Florida: Clay, Franklin, Hillsborough, Levy, Liberty, Osceola, Pasco, Union, Wakulla, and Walton.

- ↑ Conde, L.F., B.F. Swindel, and J.E. Smith. (1986). Five Years of Vegetation Changes Following Conversion of Pine Flatwoods to Pinus elliottii Plantations. Forest Ecology and Management 15(4):295-300.

- ↑ Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Lewis, C.E., G.W. Tanner, and W.S. Terry. (1988). Plant responses to pine management and deferred-rotation grazing in north Florida. Journal of Range Management 41(6):460-465.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 14 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kay Kirkman, unpublished data, 2015.

- ↑ Carlson, J. E., E. S. Menges, and P. L. Marks. 2003. Seed dispersal by Gopherus polyphemus at Archbold Biological Station, Florida. Florida Scientist, v. 66, no. 2, p. 147-154.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Hardin, J.W., Arena, J.M. 1969. Human Poisoning from Native and Cultivated Plants. Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina.