Helianthus angustifolius

| Helianthus angustifolius | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Tracheophyta- Vascular plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Ericaceae |

| Genus: | Helianthus |

| Species: | H. angustifolius |

| Binomial name | |

| Helianthus angustifolius L. | |

| |

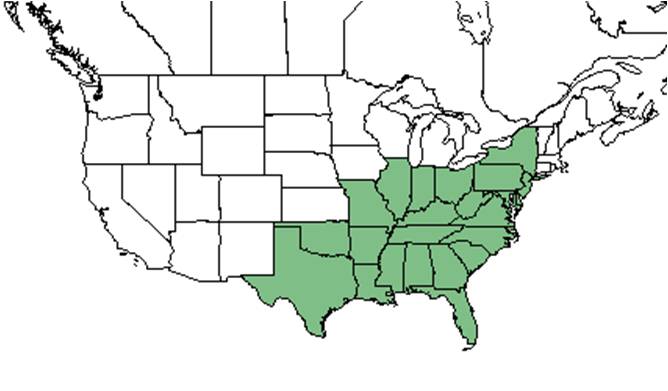

| Natural range of Helianthus angustifolius from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: swamp sunflower; swamp sneezeweed; narrowleaf sunflower

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: Helianthus angustifolius var. angustifolius; H. angustifolius var. planifolius Fernald[1]

Description

A description of Helianthus angustifolius is provided in The Flora of North America. Flowers are usually about 2 inches in diameter, and overall size class of the plant is between 1 and 3 feet tall.[2]

Distribution

Helianthus angustifolius is mostly found along the southeastern coastal plain, but is distributed from Long Island, New York south to central peninsular Florida and west to Texas, as well as irregularly inland up to Ohio, Missouri, and Indiana.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Generally, this species is found in savannas, marshes, ditches, and other wet habitats.[1] It is also found in various floodplains and bottomlands, and prefers partial shade in a variety of soils including sandy, sandy loam, medium loam, clay loam, clay, and acid-based soils.[2] Habitats that Helianthus angustifolius has been observed in include sandy pinewoods, pine savannas, partially shaded mesic pine flatwoods, old field sites, open fields, dry ridges and ridge thickets, open banks of small streams, various low areas, pitcher plant bogs and swamps, swales, moors, pond banks, marsh margins, and others. It was also found to be tolerant of disturbances, since it was found in roadsides, along powerlines, and in clearcut areas. Other soils it was found growing on include muck and wet sands, and wet sandy peat.[3] It is listed by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service as a facultative wetland species, where it is more often found in wetland habitats, but can also be found in non-wetland habitats.[4] As well, it is considered an indicator species of the upper panhandle savannas and native ground cover in southern Georgia and northern Florida.[5]

Helianthus angustifolius is an indicator species for the Upper Panhandle Savannas community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[6]

H. angustifolius was found to become absent or decrease its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in southwest Georgia. It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished pinelands that were disturbed by agricultural practices.[7]

Associated species include Pinus taeda, Pinus elliottii,Pinus palustris, Carphephorus sp., Solidago stricta, Rudbeckia sp., Liatris sp., Naccharis sp., Lobelia sp., Coelorachis rugosa, Hyptis alata, Vitis rotundifolia, Rhexia sp., and grasses.[3]

Phenology

H. angustifolius has been observed to flower from July to December, and fruit during the same time period.[8][3] It is considered very showy along roadsides when it is in flower, especially in October.[1] As well, this species was found to flower three months are a fire disturbance.[3]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind.[9]

Seed bank and germination

Helianthus angustifolius was found present in the seed bank at a loblolly pine plantation in southwest Georgia, but not in high abundance.[10]

Fire ecology

Populations of Helianthus angustifolius have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[11][12] It grows in areas that are frequently burned, and flowers in response to fire disturbance.[3] Fire disturbance has been shown to increase the occurrence of this species.[13] As well, H. Angustifolius benefits most from high fire return intervals.[14] Seasonality of burns did not seem to affect H. Angustifolius within a Louisiana longleaf pine site.[15]

Pollination

Helianthus angustifolius has been observed to host aphids such as Uroleucon sp. (family Aphididae), bees such as Melissodes tincta (family Apidae), and treehoppers such as Entylia carinata (family Membracidae).[16] The plant is considered by pollination ecologists to be of special value to native bees since it attracts such large numbers for pollination.[2] It is also pollinated by insects, mostly flies but also beetles, and Lepidoptera species.[17]

Herbivory and toxicology

H. angustifolius consists of approximately 5-10% of the diet for various large mammals, small mammals, and terrestrial birds.[18] This species is a source of food for northern bobwhite quail.[19]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

H. angustifolius should avoid soil disturbance by agriculture to conserve its presence in pine communities.[7] It is listed as threatened by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, Endangered Species Protection Board, and by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Land and Forests. As well, it is listed as extirpated by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.[4] This species is also considered to be an exotic species in West Virginia.[17]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 21, 2019

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: May 2019. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Raymond Athey, Wilson Baker, Fred A. Barkley, C. Ritchie Bell, S. Bennett, Kurt E. Blum, S. Boyce, Ted Bradley, J. John Brady, K. Craddock Burks, A. F. Clewell, H. S. Conard, W. Cooper, D. S. Correll, Delzie Demaree, Wilbur H. Duncan, Joseph Ewan, G. Fleming, William B. Fox, P. Genelle, J. P. Gillespie, R. K. Godfrey, Rnady Haynes, Norlan C. Henderson, S. C. Hood, D. C. Hunt, S. B. Jones, Samuel B. Jones, Jr., Brian R. Keener, Lisa Keppner, Gary R. Knight, R. Komarek, R. Kral, H. Kurz, O. Lakela, S. W. Leonard, Peter S. Mathies, Sidney McDaniel, Herbert Monoson, J. Richard Moore, D. E. Moreland, John Morrill, John B. Nelson, R. A. Norris, Katelin D. Pearson, James D. Ray, Jr., P. L. Redfearn, Jr., L. L. Reese, W. D. Reese, H. F. L. Rock, M. Sears, L. H. Shinners, B. C. Tharpe, and Charles S. Wallis. States and Counties: Alabama: Baldwin, Limestone, Macon, Marion, Monroe, and Talladega. Arkansas: Drew, Greene, and Saline. Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Charlotte, Citrus, Duval, Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Hernando, Hillsborough, Holmes, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Pinellas, Polk, Santa Rosa, Taylor, Wakulla, Walton, and Washington. Georgia: Bartow, Brantley, Colquitt, Decatur, Grady, Seminole, and Thomas. Kentucky: Lyon. Louisiana: Lafayette, Morehouse, and Washington. Mississippi: Covington, Harrison, Lamar, and Oktibbeha. North Carolina: Brunswick, Cabarrus, Hertford, Person, and Robeson. Oklahoma: Sequoyah. Tennessee: Coffee, Cumberland, and Macon. South Carolina: Allendale and Orangeburg. Texas: Freestone, Galveston, Gonzales, Henderson, Robertson, and Van Zandt.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 21 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson (2007). A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, south Georgia, USA. Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems, Tallahassee, Tall Timbers Research Station.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Andreu, M. G., et al. (2009). "Can managers bank on seed banks when restoring Pinus taeda L. plantations in Southwest Georgia?" Restoration Ecology 17: 586-596.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Haywood, J. D., et al. (1995). Responses of understory vegetation on highly erosive Louisiana soils to prescribed burning in May. Asheville, NC, USDA Forest Service, Research Note SO-383: 8.

- ↑ Mehlman, D. W. (1992). "Effects of fire on plant community composition of North Florida second growth pineland." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 119(4): 376-383.

- ↑ Haywood, J. D., et al. (2001). "Vegetative response to 37 years of seasonal burning on Louisiana longleaf pine site." Southern Journal of Applied Forestry 25: 122-130.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 [[3]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: May 21, 2019

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Chenault, T. P. (1940). "The phenology of some bob-white food and cover plants in Brazos County, Texas." The Journal of Wildlife Management 4(4): 359-368.