Dichanthelium ovale

oval-flowered witchgrass; low stiff witchgrass

| Dichanthelium ovale | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Genus: | Dichanthelium |

| Species: | D. ovale |

| Binomial name | |

| Dichanthelium ovale (Elliot) Gould & C.A. | |

| |

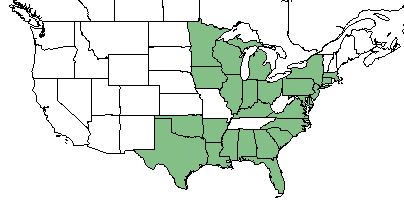

| Natural range of Dichanthelium ovale from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Dichanthelium commonsianum (Ashe) Freckmann; Panicum commonsianum Ashe; P. ovale Elliott var. pseudopubescens (Nash) Lelong; Dichanthelium ovale ssp. ovale; P. ovale Elliott; P. ovale var. ovale Lelong[1]

Varieties: Dichanthelium ovale (Elliott) Gould & Clark var. addisonii (Nash) Gould & Clark; Dichanthelium ovale (Elliott) Gould & Clark var. ovale; D. wilmingtonense (W.W. Ashe) Wipff; Panicum addisonii Nash; P. commonsianum W.W. Ashe; P. commonsianum var. addisonii (Nash) Fernald; P. commonsianum var. commonsianum; P. mundum Fernald; P. wilmingtonense Ashe[1]

Description

Also known as eggleaf rosette grass, Dichanthelium ovale is a native perennial graminoid that is a member of the Poaceae family. It has a rapid growth rate reaching a mature height of 1.7 meters on average, and a short lifespan. [2] It is distinguished from D. consanguineum by the upper blade surface being glabrous with few short basal hairs while D. consanguineum has strongly pilose upper surfaces on the leaf blade.[1]

D. ovale does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its fibrous roots.[3] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have a water content of 54.1% (ranking 69 out of 100 species studied).[3]

Distribution

D. ovale grows in the eastern United States, ranging from east Texas up to New York and Michigan, excluding West Virginia, Tennessee, and Missouri.[2] D. ovale var. ovale is distributed from New York to Wisconsin as well as south Florida and west to eastern Texas. D. ovale var. addisonii can be found from Massachusetts and Minnesota south to Florida and Texas, and is also native to northern Mexico.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

D. ovale var. addisonii grows in a range of dry to damp soils and in sandy woods and fields, while D. ovale var. ovale grows in damp to dry and sandy pinelands.[1] More specifically, D. ovale has been observed in a range of habitats including open limestone glades, moist soil, longleaf pineland bogs, moist sandy peat, coarse sand habitats, abandoned fields, sandhills, and other sandy loams. [4] It has been seen to be more abundant in disturbed areas. [5] It is listed as a facultative upland species, where it is mostly found in upland non-wetland habitats but can occasionally be found in wetlands as well.[2] It prefers partial shade and low amount of water use.[6] In Florida, D. ovale is abundant in the xeric sandhills of the peninsula and the panhandle.[7]

Associated species: Aristida beyrichiana, Sorghastrum secundum, and Schizachyrium scoparium var. stoloniferum.[7]

Dichanthelium ovale var. addisonli is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills, Panhandle Xeric Sandhills, North Florida Longleaf Woodlands, North Florida Subxeric Sandhills, and Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[8]

Phenology

The species flowers in the springtime beginning in May, and continues to develop fruit throughout October.[9] Fruit has been seen in the months March through June and August. [4]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity. [10]

Seed bank and germination

A study found seeds of D. ovale to persist in the seed bank on a restoration project even when herbaceous cover of the species was not found. It was found to germinate at the restoration site with high frequency.[11]

Fire ecology

D. ovale is mostly found in fire dependent pinelands in sandhill communities,[7] with populations known to persist through repeated annual burns.[12][13] This was also seen by a fire exclusion study, where this species disappeared when fire regiments were ceased.[14]

Pollination

Like other grasses, flowers of the Dichanthelium genus are self-pollinated.[6]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 USDA Plants Database URL: https://plants.usda.gov/java/charProfile?symbol=DIOV

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Wilson Baker, Cecil R. Slaughter, R. Kral, R. K. Godfrey, R. L. Wilbur, G. W. Pamelee, John W. Thieret, A. E. Radford, Steve Mortellaro, Brenda Herring, Don Herring, D. L. Martin, S. T. Cooper, R. Wunderlin, Bruce Hansen, G. Robinson, Steve L. Orzell, E. L. Bridges, R. Komarek, Andre F. Clewell, George R. Cooley, Richard J. Eaton, Leonard J. Brass, R. D. Houlk, J. B. McFarlin, J. Beckner, C. Chapman, R. R. Smith, A. H. Curtiss, Robert F. Thome, R. A. Davidson, Sidney McDaniel, Nancy Coile, G. Smith, N. MacLeish, M. Garland, D. Coile, Richard Carter, Raymond Athey, D. J. Banks, H. Kurz, and Annie Schmidt. States and counties: Florida: Leon, Liberty, Bay, Gadsden, Madison, Wakulla, Calhoun, Jackson, Clay, Franklin, Okaloosa, Duval, Walton, Escambia, Highlands, Gilchrist, Levy, Citrus, Suwannee, Sumter, Columbia, Lee, and Volusia. Alabama: Washington, Lee, Mobile, and Monroe. North Carolina: Pender, Beaufort, and Brunswick. Georgia: Wheeler, Thomas, Decatur, Baker, Walker, and Emanuel. Michigan: Allegan, and Montcalm. Louisiana: Allen, Ouachita, Union, and Natchitoches. South Carolina: Kershaw. Virginia: Roanoke. South Carolina: Berkeley. Tennessee: Coffee. Kentucky: Crittenden.

- ↑ Rodgers, H. L. and L. Provencher (1999). "Analysis of Longleaf Pine Sandhill Vegetation in Northwest Florida." Castanea 64(2): 138-162.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 1, 2019

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedWeakley - ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Andreu, M. G., et al. (2009). "Can managers bank on seed banks when restoring Pinus taeda L. plantations in Southwest Georgia?" Restoration Ecology 17: 586-596.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2014). "Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned old field pine woodland, Florida." Castanea 79: 147-167.