Dichanthelium villosissimum

| Dichanthelium villosissimum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Illinois Wildflowers | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae - Grasses |

| Genus: | Dichanthelium |

| Species: | D. villosissimum |

| Binomial name | |

| Dichanthelium villosissimum (Nash) | |

| |

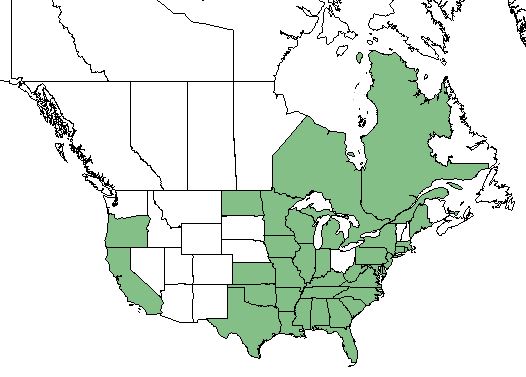

| Natural range of Dichanthelium villosissimum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common Name(s): white-haired witchgrass, whitehair rosette grass[1][2], hairy panic grass;[3] white-haired panic grass[4]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Dichanthelium acuminatum (Swartz) Gould & Clark var. villosum (A. Gray) Gould & Clark; D. ovale (Elliott) Gould & Clark ssp. villosissimum (Nash) Freckmann & Lelong; Panicum ovale Elliott var. villosum (A. Gray) Lelong; P. pseudopubescens Nash; P. villosissimum Nash; P. villosissimum var. pseudopubescens (Nash) Fernald; P. villosissimum var. villosissimum.[5]

Variations: none.[5]

Description

D. villosissimum is a monoecious perennial graminoid[2] that can be found growing in small clumps.[6] It can reach heights of about 18 inches.[7]

Distribution

This species is found from Maine and Massachusetts south to Florida and westward to Texas, the Dakota's, Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma. It is also recorded in Oregon and California as well as eastern Canada and parts of Mexico and Mesoamerica.[1][2]

Ecology

Habitat

D. villosissimum is found in dry sandy soils of open woodlands and prairies.[1] In Illinois, U.S.A., a study comparing mature dry sand prairies with two successional fields (60 and 30 years) showed the frequency and average cover of D. villosissimum increased with increasing length of succession. This suggests it colonizes slowly compared to other species.[3][8] On Illinois dry sand prairies in 1908, D. villosissimum was responsible for up to 75% of vegetation cover [9] In loamy longleaf pine savannas, D. villosissimum abundance was directly correlated with light levels indicating D. villosissimum is a heliophyte.[10] This species has also been observed in open sand edges of drying muck holes that are widley scattered in an open meadow as well as adjacent roadside.[11] D. villosissimum responds positively to soil disturbance by roller chopping in Northwest Florida sandhills.[12]

Phenology

Flowering and fruiting occur between April and September.[1]

Seed bank and germination

Densities of seeds in the seed banks of Indiana oak savannas averaged a density of 32 seeds per square meter. In secondary dunes, densities had a mean of 45 seeds per square meter.[13] Seeds in the seed bank are also more frequent in older successional habitats.[8]

Fire ecology

Fire was shown to increase the frequency of D. villosissimum and other C3 plants in Illinois dry sandstone barrens and Florida longleaf pine sandhills, especially where wiregrass is dominant.[14][15] They are common in frequently burned (1-2 year fire return interval) upland longleaf pine and old-field pine communities of northern Florida and southern Georgia.[16]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

D. villosissimum var. praecocius is listed as endangered by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Natural Areas and Preserves. D. villosissimum var. villosissimum is listed as a species of special concern by the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, and listed as presumed extirpated by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Natural Areas and Preserves.[2]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Weakley A. S.(2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 7 December 2017). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 McClain W. E., Schwegman J. E., Strole T. A., Phillippee L. R., and Ebinger J. E. (2008). Floristic study of sand prairie-scrub oak nature preserve, Mason County, Illinois. Castanea 73(1):29-39

- ↑ Pavlovic N. B., Leicht-Young S. A., and Grundel R. (2011). Short-term effects of burn season on flowering phenology of savanna plants. Plant Ecology 212(4):611-625.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ McClain W. E., Phillippe L. R., and Ebinger J. E. (2005). Floristic assessment of the Henry Allan Gleason Nature Preserve, Mason County, Illinois. Castanea 70(2):146-154.

- ↑ [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 2, 2019

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Oosting H. J. and Humphreys M. E. (1940). Buried viable seeds in a successional series of old field and forest soils. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 67(4):253-273.

- ↑ Robertson K. R., Phillippe L. R., Levin G. A., and Moore M. J. (1997). Delineation of natural communities, a checklist of vascular plants, and new locations for rare plants at the Savanna Army Depot, Carroll and Jo Daviess Counties, Illinois. University of Illinois, Urbanna-Champaign, Illinois.

- ↑ Platt W. J., Carr S. M., Reilly M., Fahr J. (2006). Pine savanna overstorey influences on ground-cover biodiversity. Applied Vegetation Science 9:37-50.

- ↑ Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: May 2019. Collectors: John B. Nelson. States and Counties: South Carolina: Lexington.

- ↑ Hebb, E.A. (1971). Site Preparation Decreases Game Food Plants in Florida Sandhills. The Journal of Wildlife Management 35(1):155-162.

- ↑ Leicht-Young S. A., Pavlovic N. B., Grundel R., and Frohnapple K. (2009). A comparison of seed banks across a sand dune successional gradient at Lake Michigan dunes (Indiana, USA).

- ↑ Taft J. B. (2003). Fire effects on community structure, composition, and diversity in a dry sandstone barrens. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 130(3):170-192.

- ↑ Rodgers H. L. and Provencher L. (1999). Analysis of longleaf pine sandhill vegetation in Northwest Florida. Castanea 64(2):138-162.

- ↑ Robertson, Kevin R. 2017. Personal observations and records for the Red Hills Region of northern Florida and southern Georgia.