Coreopsis lanceolata

Common Names: Lanceleaf Tickseed;[1] Sand Coreopsis;[2] Longstalk Coreopsis

| Coreopsis lanceolata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Genus: | Coreopsis |

| Species: | C. lanceolata |

| Binomial name | |

| Coreopsis lanceolata L. | |

| |

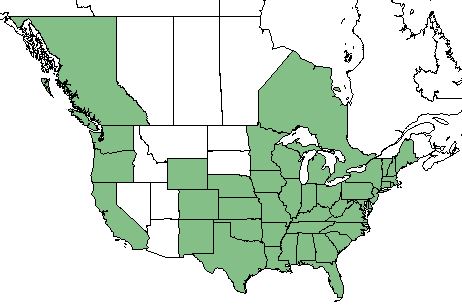

| Natural range of Coreopsis lanceolata from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: C. heterogyna Fernald, C. crassifolia Aiton.[3]

Varieties: none.[3]

Description

C. lanceolata is a perennial forb/herb of the Asteraceae family native to North America.[1] It is a clump-forming plant that has short rhizomes, the leaves can be hairy or smooth, and the basal leaves are divided while the upper leaves are oval-shaped and entire. The flower head inflorescence is borne singularly or in small groups, which are yellow in color. The seeds are winged, dark brown, and almost semi-circular to curved.[4]

Distribution

C. lanceolata is native throughout the United States apart from Arizona, Nevada, Idaho, Utah, Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota. It is also native in Ontario and British Columbia, and has been introduced to Hawaii and the Pacific Basin.[1] This species is often spread by cultivation, and the original range of the species is obscure.[5]

Ecology

Habitat

The species can be found in disturbed areas, savannas, meadows, pastures, prairies, plains, and open woodlands.[5][6] C. lanceolata is listed as a facultative upland and obligate upland species, where it mostly can be found in upland communities but uncommonly in wetlands.[1] The ideal habitat for the C. lanceolata is in dry soil with full sun, but it can tolerate light shade as well.[4] Other habitats that C. lanceolata has been observed in include limestone glades, borders of cypress depressions, naturalization from gardens, and sand dunes. Soils it has been observed to grow on include sandy soil, moist sandy loam, silty-sandy soil, sandy-clayey, and sandy peat.[7]

Associated species: Quercus laevis, Quercus sp., Pinus palustris, Pinus taeda, Oenothera laciniata, Trifolium repens, Trifolium dubium, Trifolium incarnatum, Anthoxanthum odoratum, Lolium perenne, Salvia lyrata, Briza minor, Silene antirrhina, Ilex glabra, and Coreopsis bakeri.[7]

Phenology

Flowering of the C. lanceolata has been observed to flower between January and July, with peak inflorescence between March and May, producing the majority of the buds. [8] It has been observed to fruit from April through June as well as August.[7]

Seed bank and germination

For successful seedlings, a firm seedbed is needed that has been lightly disked. Light plant debris is ideal; more will stifle plant germination. Germination occurs in the fall. [1]

Fire ecology

C. lanceolata has been observed in areas that are frequently burned.[7]

Pollination and use by animals

Species of the Hymenoptera order that have been observed to pollinate C. lanceolata at the Indiana Dunes and Northwest Indiana include Bombus impatiens, Nomada fervida, Nomada lepida, Nomada maculata, Ceratina mikmaqi, Ceratina strenua, Augochlora pura, Augochlorella aurata, Augochloropsis metallica, Halictus ligatus, Lasioglossum pectorale, Lasioglossum fuscipenne, Sphecodes pimpinellae, Megachile mendica, and Osmia georgica.[9] The karner blue butterfly (Lycaeides melissa samuelis) is also known to pollinate this plant.[10] Additionally, this species is visited by ground-nesting bees from the Andrenidae family (Andrena hippotes), bees from the Apidea family such as Bombus fervidus, Bombus melanopygus, Ceratina calcarata, Diadasia bituberculata and Diadasia enavata), plasterer bees from the Colletidae family (Hylaeus mesillae), sweat bees from the Halictidae family (Agapostemon virescens and Halictus ligatus), leafcutting bees from the Megachilidae family (Ashmeadiella sp., Megachile sp. and Osmia sp.) and hoverflies from the Syrphidae family (Eristalis transversa).[11] This species is of special value to native bees and supports conservation biological control through attracting predatory or parasitoid insects that in turn prey on pest insects.[6]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

This species can withstand regular mowing in the summer and fall, but if it is allowed to regrow after initial mowing, C. lanceolata will usually flower inconsistently during the summer. With this, fall mowing is recommended.[4]

Cultural use

Historically, plants in the Coreopsis genus were utilized by Native Americans to make a natural red dye.[12]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 USDA Plant Database

- ↑ Goldblum, D., et al. (2013). "The impact of seed mix weight on diversity and species composition in a tallgrass prairie restoration planting, Nachusa grasslands, Illinois, USA." Ecological Restoration 31(2): 154-167.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Whitten, Jamie L. (2006). Plant Fact Sheet: Lance-leaf coreopsis Coreopsis lanceolata. N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture. Coffeeville, MS.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 16, 2019

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: March 2019. Collectors: J. Richard Abbott, Harry E. Ahles, Loran C. Anderson, Raymond Athey, Wilson Baker, J. Beckner, C. R. Bell, K. E. Blum, E. Bourdo, S. G. Boyce, Keith A. Bradley, Edwin L. Bridges, Michael B. Brooks, M. Burch, A. F. Clewell, George R. Cooley, Delzie Demaree, William B. Fox, J. P. Gillespie, R.K. Godfrey, S. R. Harrison, N. C. Henderson, M. Hobbs, W. C. Holmes, Clarke Hudson, D. C. Hunt, Ann F. Johnson, Carleen Jones, Samuel B. Jones, Gary R. Knight, M. Knott, R. Komarek, R. Kral, R L Lazor, Amelia Lundell, C. L. Lundell, Sidney McDaniel, John B. Nelson, R. A. Norris, Steve L. Orzell, Richard D. Porcher, Elmer C. Prichard, A. E. Radford, Paul L. Redfearn, Jr., J. D. Reynolds, E L Stone, Victoria I. Sullivan, John W. Thieret, B. L. Turner, B. H. Warnock, D. R. Windler, and Jean Wooten. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Madison, Okaloosa, Wakulla, and Walton. Georgia: Grady and Thomas. Alabama: Geneva and Lee. Arkansas: Baxter and Sevier. Indiana: Huntington and La Grange. Kentucky: Madison and Trigg. Louisiana: Acadia, Jackson, Natchitoches, Ouachita, Rapides, Union, and Vernon. Maryland: Sussex. Michigan: Emmet and Mackinac. Mississippi: Attala, Carroll, Forrest, Jefferson Davis, Lowndes, Newton, Oktibbeha, Pearl River, Scott, and Stone. Missouri: Greene and Shannon. North Carolina: Buncombe, Granville, and Pender. South Carolina: Chesterfield, Clarendon, Hampton, Jasper, McCormick, Richland, and Saluda. Tennessee: Coffee, Lewis, and Wilson. Texas: Angelina, Harris, Walker, and Waller.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 18 MAY 2018

- ↑ Grundel, R., et al. (2011). "A survey of bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of the Indiana Dunes and Northwest Indiana, USA." Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 84(2): 105-138.

- ↑ Grundel, R., et al. (2000). "Nectar plant selection by the Karner blue butterfly (Lycaeides melissa samuelis) at the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore." The American Midland Naturalist 144(1): 1-10.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]

- ↑ Rafinesque, C. S. (1828). Medical flora; or Manual of the medical botany of the United States of North America.