Smilax rotundifolia

| Smilax rotundifolia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Gwaltney hosted at Southeastern Flora.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Liliales |

| Family: | Smilacaceae |

| Genus: | Smilax |

| Species: | S. rotundifolia |

| Binomial name | |

| Smilax rotundifolia L. | |

| |

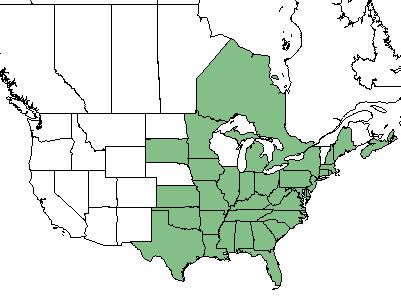

| Natural range of Smilax rotundifolia from USDA NRCS [1]. | |

Common Names: Common greenbriar; bullbriar; horsebriar;[1] roundleaf greenbrier[2]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonym: none

Varities: S. rotundifolia var. quadrangularis (Muhlenberg ex Willdenow) Wood

Description

S. rotundifolia is a monoecious perennial that grows as a shrub or vine.[2]

Distribution

The distribution of S. rotundifolia ranges from eastern Texas, westward to northern Florida, and northward into the provinces of Nova Scotia and Ontario Canada.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

S. rotundifolia is found in a variety of upland and wetland habitats.[1] S. rotundifolia responds positively to soil disturbance by heavy silvilculture in North Carolina.[3] It also responds positively or not at all to soil disturbance by clearcutting and roller chopping in North Florida.[4] However, S. rotundifolia responds negatively or not at all to soil disturbance by improvement logging in Mississippi.[5]

Phenology

In the southeastern and mid-Atlantic United States, S. rotundifolia flowers from April through May with fruiting occurring in September through November and persisting beyond.[1]

Fire ecology

Controlled burns conducted during the spring of 2001 and 2004 in an Ohio mixed-oak hardwood forest had the fire spread at mean rates of 6.2-11.3 m min-1 (as cited in[6]). These burns significantly reduced the mean percent cover of S. rotundifolia from 10.9% in 2001 and 8.1% in 2004 to 0.7 and 1.1%, respectively. The combination of burn and winter thinning yielded similar results producing mean coverage of 0.7 and 1.9% for 2001 and 2004, respectively.[6] Burns also increase the level of crude protein in S. rotundifolia,[7] which may alter browsing pressure. In the white pine and white pine-hardwood forests of New Hampshire, low intensity spring and fall fires top kill S. rotundifolia. Following these burns, S. rotundifolia vigorously reappears through vegetative reproduction.[8]

Pollination

The pollen of S. rotundifolia is linked via viscin threads that prevent it from being wind dispersed; instead, it relies on insects for pollination.[9]

Use by animals

Smilax rotundifolia comprises 5-10% of the diet of several large mammals, small mammals, and terrestrial birds.[10] Leave and twigs of S. rotundifolia are known to have been consumed by the Florida marsh rabbit (Sylvilagus palustris paludicola).[11]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Winter thinning in an Ohio mixed-oak hardwood forest reduced the mean percent coverage of S. rotundifolia from 10.9% to 3.1%. This reduced value was still higher than the reduction of cover produced by burning, suggesting burning to be more effective in reducing the coverage of S. rotundifolia.[6]

Cultural use

There are many species of Smilax and it is thought they can all be used in similar ways. Historically, the roots were harvested and prepared in a red flour or a thick jelly that could be used in candies and sweet drinks. Our first known written account of using the plant roots to make this jelly is from the journal of Captain John Smith in 1626. Other travelers throughout US history have made note of the uses of Smilax plants. We know the flour was used in breads and soups, and that a drink very similar to Sarsaparilla could be prepared. The shoots of this particular species are also edible without cooking, and can be used to make salads.[12]

The jelly from this particular species comes out tea-colored.[13]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Weakley AS (2015) Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 USDA NRCS (2016) The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 23 January 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ Cohen, S., R. Braham, and F. Sanchez. (2004). Seed Bank Viability in Disturbed Longleaf Pine Sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.

- ↑ Lewis, C.E., G.W. Tanner, and W.S. Terry. (1988). Plant responses to pine management and deferred-rotation grazing in north Florida. Journal of Range Management 41(6):460-465.

- ↑ McComb, W.C. and R.E. Noble. (1982). Response of Understory Vegetation to Improvement Cutting and Physiographic Site in Two Mid-South Forest Stands. Southern Appalachian Botanical Society 47(1):60-77.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Albrecht MA, McCarthy BC (2006) Effects of prescribed fire and thinning on tree recruitment patterns in central hardwood forests. Forest Ecology and Management 226:88-103.

- ↑ DeWitt JB, Derby, JV Jr. (1955) Changes in nutritive value of browse plants following forest fires. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 19(1)65-70.

- ↑ Chapman RR, Crow GE (1981) Application of Raunkiaer's life form system to plant species survival after fire. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 108(4):472-478.

- ↑ Kevan PG, Ambrose JD, Kemp JR (1991) Pollination in an understory vine, Smilax rotundifolia, a threatened plant of the Carolinian forests in Canada. Canadian Journal of Botany 69:2555-2559.

- ↑ Miller JH, Miller KV (1999) Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Blair WF (1936) The Florida marsh rabbit. Journal of Mammalogy 17(3):197-207.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.