Amianthium muscitoxicum

| Amianthium muscitoxicum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Liliales |

| Family: | Liliaceae |

| Genus: | Amianthium |

| Species: | A. muscitoxicum |

| Binomial name | |

| Amianthium muscitoxicum (Walter) A. Gray | |

| |

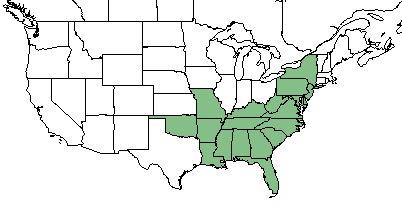

| Natural range of Amianthium muscitoxicum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common Names: fly-poison;[1][2][3] stagger grass; crow poison; fall poison;[3]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Chrosperma muscaetoxicum (Walter) Kuntze; Zigadenus muscitoxicus (Walter) Regel;[1][2]

Description

Amianthium muscitoxicum is a monoecious perennial forb/herb.[2] It has narrow elongated leaves and reaches lengths of 12-24 in (30-61 cm).[4] However, earlier sources report it reaching heights of 1.5-4 ft (0.46-1.22 m).[3] Flowers are initially white, but turn a bronzy-green, and occur in dense showy racemes. All parts of the plant are poisonous, containing a very toxic alkaloid.[5][4] In a study, the average fruit set, seeds per fruit, and total seeds per plant ranged from 0.59-0.67, 1.72-2.27, and 16.7-20.7, respectively, depending upon the pollination distance.[6] Fruits are red and the plant grows grows from a coated bulb 2-3 in (5.1-7.6 cm) below the soil surface.[3]

Distribution

This species occurs from southern New York, Pennsylvania, Missouri, and Oklahoma, southward to the Florida panhandle, Mississippi, and Arizona.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

A. muscitoxicum occurs from 5-1,600 m in elevation across a wide variety of mesic to dry forests, pine savannas, sandhills, and meadows.[1] It has been observed in a range of habitats including along steep ravine slopes, by creeks, in low pinelands and bottomland woodlands, boggy draws and sphagnous flats, and in loamy sands along wooded slopes.[7] It is reported to grow in Virginia at an elevation of 4,000 ft (1,219 m) and inhabits sandy soils throughout its range.[3] In a North Carolina longleaf pine study, A. muscitoxicum vegetation was present only in disturbed sites.[8]

Phenology

In the Southeastern and mid-Atlantic United States, flowering occurs from May through July and fruiting from July through September.[1]

Seed bank and germination

Despite being present in a North Carolina disturbed longleaf pine habitat, no evidence of its presence in the seed bank was found.[8]

Fire ecology

A. muscitoxicum has been observed in pinelands that are annually burned, and seems to benefit from fire regiments.[7]

Pollination

The distance of pollinating neighbors has some influence on the production and weight of seeds. However, heterogeneity between plants accounted for a greater amount of variance between seed production and weight.[9][6] In Virginia, at least 16 species serve as pollinators to A. muscitoxicum, including Trichiotinus affinus (hairy flower scarab), Anoplodera octonotata, A. vittata, A. circumdata, Grammoptera haematites, Leptura lineola, Encyclops coerulea, Callimoxys sanguinicollis, Odontota dorsalis, Epargyreus clarus (silver-spotted skipper), Celastrina argiolus (holly blue), Papilio glaucus (eastern tiger swallowtail), Colias philodice (common sulphur or clouded sulphur), Apis mellifera (European honey bee), and Xylocopus americanus (carpenter bee).[9]

Use by animals

Humans use it to kill flies by taking the pulp from crushed bulbs and mixing it with sugar.[4] Native Americans would also use A. muscitoxicum to kill crows and as a severe cure for the itch.[10] It is also poisonous to other animals, being capable of killing a sheep within 24 hours of consumption and even sicken or kill larger cattle including mules and horses. Such poisonings usually occur in the spring when the 4-6 in (10.2-15.2 cm) green grass-like leaves start to grow.[3]

Diseases and parasites

Rust, caused by a fungi, can occur on A. muscitoxicum.[11]

Conservation and Management

A. muscitoxicum is listed as threatened by the state of Kentucky.[12]

Cultivation and restoration

Propagation can be performed by planting seeds when ripe in the spring or through rood divisions.[4]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley AS (2015) Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 USDA NRCS (2016) The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 21 February 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Marsh CD, Clawson AB, Marsh H (1918) Stagger grass (Chrosperma muscaetoxicum) as a poisonous plant. United States Department of Agriculture Bulletin 710:1-14.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Plant database: Amianthium muscitoxicum. (21 February 2018) Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. URL: https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=AMMU

- ↑ Neuss N (1953) A new alkaloid from Amianthium muscaetoxicum Gray. Journal of the American Chemical Society 75(11):2772-2773.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Redmond AM, Robbins LE, Travis J (1989) The effects of pollination distance on seed production in three populations of Amianthium muscaetoxicum (Liliaceae). Oecologia 79:260-264.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: March 2019. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Wilson Baker, Robert K. Godfrey, J. M. Kane, R. A. Norris, and Rodie White. States and Counties: Florida:Gadsden, Leon, and Washington. Georgia: Grady and Thomas.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Cohen S, Braham R, Sanchez F (2004) Seed bank viability in disturbed longleaf pine sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Travis J (1984) Breeding system, pollination, and pollinator limitation in a perennial herb, Amianthium muscaetoxicum (Liliaceae).

- ↑ Witthoft J (1947) Ethnology - An early Cherokee ethnobotanical note. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences 37(3):73-75.

- ↑ Orton CR, Weiss F (1925) The life cycle of the rust on fly poison, Chrosperma muscaetoxicum. Mycologia 17(4):148-153.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedUSDA Plants