Manfreda virginica

| Manfreda virginica | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida – Monocotyledons |

| Order: | Liliales |

| Family: | Agavaceae |

| Genus: | Manfreda |

| Species: | M. virginica |

| Binomial name | |

| Manfreda virginica (L.) Salisb. ex Rose | |

| |

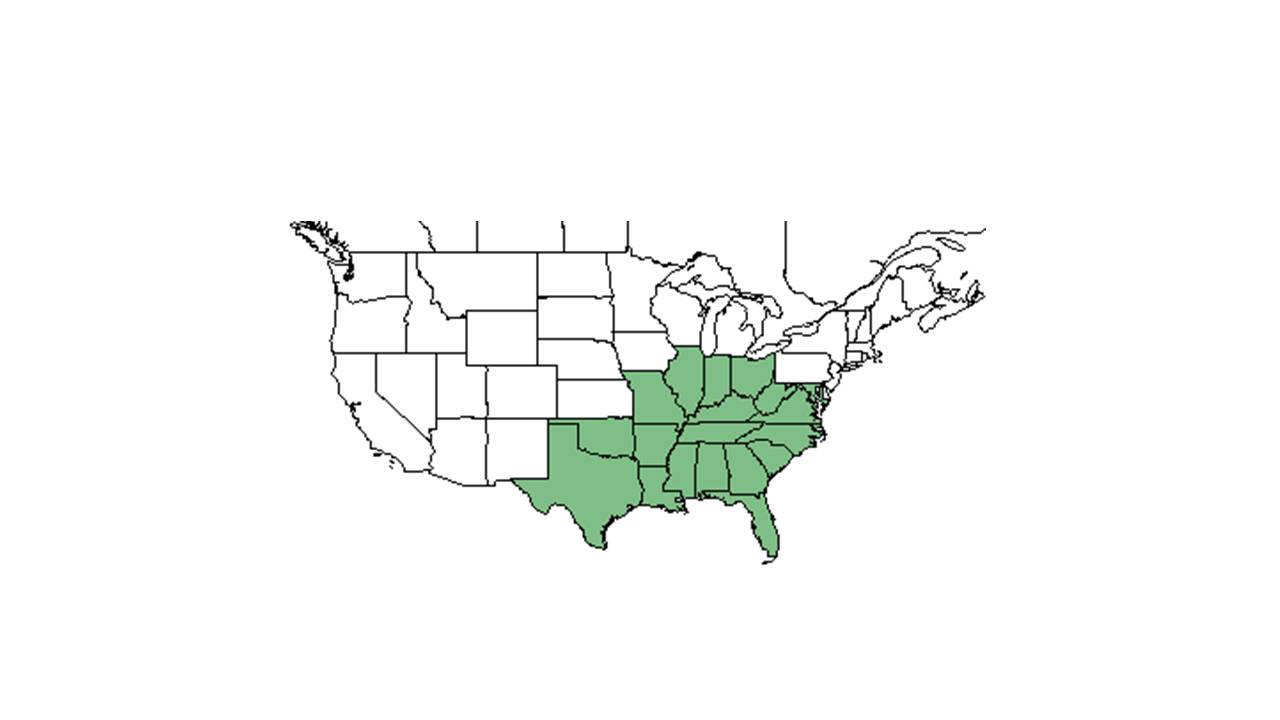

| Natural range of Manfreda virginica from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: false aloe, rattlesnake-master, eastern agave, eastern false-aloe[1]

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Agave virginica Linnaeus; Manfreda virginica (Linnaeus) Salisbury ex Rose; Manfreda virginica ssp. virginica; Polianthes virginica (Linnaeus) Shinners[1]

Varieties: Manfreda tigrina (Engelmann) Small; Manfreda virginica[1]

Description

A description of Manfreda virginica is provided in The Flora of North America.

Distribution

M. virginica ranges from eastern South Carolina, central North Carolina, southwest Virginia, western West Virginia, southern Ohio, southern Indiana, southern Illinois, and Missouri, south to central peninsular Florida and Texas.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

This species grows in well-drained or poorly-drained slopes of longleaf pine forests, savannas, mesic pine-hardwood forest remnants, granite flatrocks, diabase glades, limestone and dolomite barrens and glades, xeric woodlands over mafic or calcareous rocks, sandhill woodlands, and dry roadbanks.[2][1] It prefers sandy loam habitats and upland Coastal Plain soils that have little slope and low fertility. [3] Additionally, it thrives in semi-shaded areas to open areas. Associated species include longleaf pine, wiregrass, and hardwoods.[2]

Phenology

M. virginica flowers from late May through August and fruits from August through October.[1]

Fire ecology

This species is found in annually burned areas[2] as shown by populations of Manfreda virginica known to persist through repeated annual burns.[4][5]

Pollination

M. virginica is pollinated both diurnally and nocturnally, with observations suggesting that bumblebees are the predominant floral visitors.[6] Bombus pennsylvanicus and Hemaris diffinis are critical diurnal pollinators; however, diurnally pollinated plants were observed to produce significantly lower seed set than nocturnally and open-pollinated plants.[6] Hence nocturnal visitors contribute more to M. virginica reproduction despite frequent diurnal visits.[6]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "weakley" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Robert K. Godfrey, R. Komarek, Loran C. Anderson, and Annie Schmidt. States and Counties: Florida: Leon and Washington. Georgia: Grady and Thomas.

- ↑ Miller, J. H., R. S. Boyd, et al. (1999). "Floristic diversity, stand structure, and composition 11 years after herbicide site preparation." Canadian Journal of Forest Research 29: 1073-1083.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Groman, J. D. and O. Pellmyr (1999). "The pollination biology of Manfreda virginica (Agavaceae): relative contribution of diurnal and nocturnal visitors." Oikos 87: 373-381.